We apologize for Proteopedia being slow to respond. For the past two years, a new implementation of Proteopedia has been being built. Soon, it will replace this 18-year old system. All existing content will be moved to the new system at a date that will be announced here.

User:Alexander Grayzel/Sandbox 1

From Proteopedia

< User:Alexander Grayzel(Difference between revisions)

| (2 intermediate revisions not shown.) | |||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

Ferritin is a tetramer composed of 24 <scene name='10/1078819/Single_chain_of_ferritin/1'>subunits</scene> (24-mer) forming a hollow spherical shell, with a total molecular weight of approximately 478 kDa and a diameter of 8.66 nm. <ref name="srivastava">Srivastava, A.K., Reutovich, A.A., Hunter, N.J. et al. Ferritin microheterogeneity, subunit composition, functional, and physiological implications. Sci Rep 13, 19862 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46880-9</ref> These subunits exist in two primary forms in humans: heavy (H, 21 kDa) and light (L, 19 kDa) chains.<ref name="srivastava" /> These two chains co-assemble in various proportions (H:L) to form the iron-storage complex. The ratio of H:L is greater in tissues in which the activity of iron oxidation is at a high level and iron needs to be detoxified, for example the heart or brain. The make-up of the subunits in the shell does not affect the iron/oxy mineral composition in the core. What’s interesting is that two identical ferritin proteins, meaning proteins with the same H:L ratio, will likely have different iron cores. Additionally, the H:L ratio will have some effect on the geometry of the crystalline structure as their properties are different. | Ferritin is a tetramer composed of 24 <scene name='10/1078819/Single_chain_of_ferritin/1'>subunits</scene> (24-mer) forming a hollow spherical shell, with a total molecular weight of approximately 478 kDa and a diameter of 8.66 nm. <ref name="srivastava">Srivastava, A.K., Reutovich, A.A., Hunter, N.J. et al. Ferritin microheterogeneity, subunit composition, functional, and physiological implications. Sci Rep 13, 19862 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46880-9</ref> These subunits exist in two primary forms in humans: heavy (H, 21 kDa) and light (L, 19 kDa) chains.<ref name="srivastava" /> These two chains co-assemble in various proportions (H:L) to form the iron-storage complex. The ratio of H:L is greater in tissues in which the activity of iron oxidation is at a high level and iron needs to be detoxified, for example the heart or brain. The make-up of the subunits in the shell does not affect the iron/oxy mineral composition in the core. What’s interesting is that two identical ferritin proteins, meaning proteins with the same H:L ratio, will likely have different iron cores. Additionally, the H:L ratio will have some effect on the geometry of the crystalline structure as their properties are different. | ||

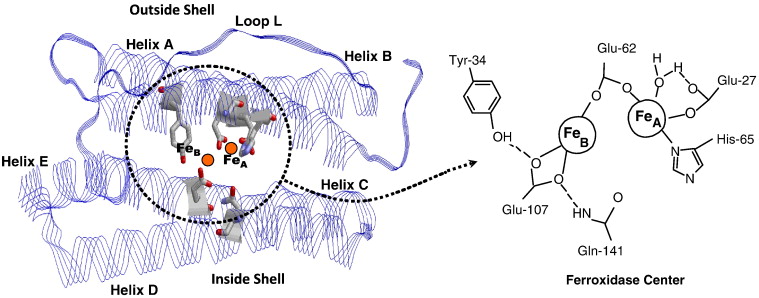

| - | Each individual subunit of the 24-mer consists of five alpha-helices and no beta-sheets, forming a couple of four-helix | + | Each individual subunit of the 24-mer consists of five alpha-helices and no beta-sheets, forming a couple of four-helix bundles (A-B and C-D) connected by loops, with a short C-terminal helix (E) providing protein stabilization.<ref name="Levi">Levi, S., & Rovida, E. (2015). Neuroferritinopathy: From ferritin structure modification to pathogenetic mechanism. Neurobiology of disease, 81, 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2015.02.007</ref> The H-chain posses ferroxidase activity, while the L-chain supports iron nucleation and mineralization. Subunits share about 55% sequence identity.<ref name="Levi" /> Iron channels on the ferritin surface are lined with polar side chains primarily of glutamate, which makes a hydrophilic channel allowing iron ions into the core. Additionally, the negative charge on glutamate acts as a good binding site for iron ions. |

== Function == | == Function == | ||

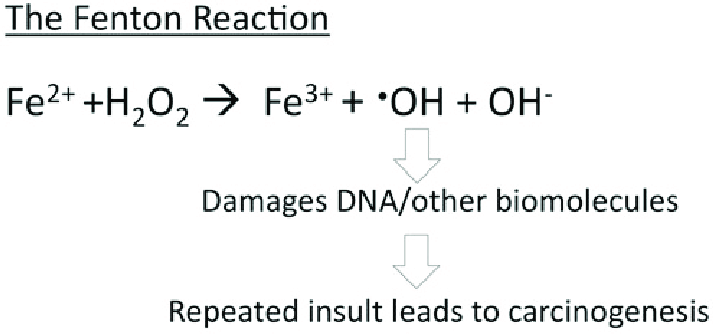

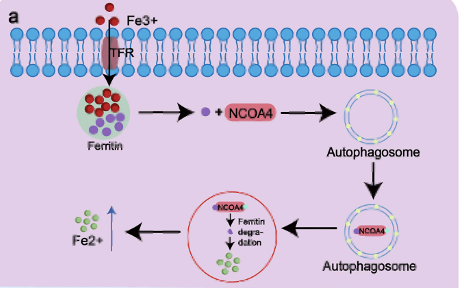

| - | Ferritin stores iron in a safe, bioavailable form. By sequestering Fe³⁺ in a mineralized core, it prevents free iron from catalyzing harmful oxidative reactions. In addition to iron storage, ferritin contributes to intracellular iron delivery, especially during high-demand situations such as rapid growth repair. Its capacity to hold more iron than | + | Ferritin stores iron in a safe, bioavailable form. By sequestering Fe³⁺ in a mineralized core, it prevents free iron from catalyzing harmful oxidative reactions. In addition to iron storage, ferritin contributes to intracellular iron delivery, especially during high-demand situations such as rapid growth repair. Its capacity to hold more iron than transferrin makes it vital for systemic iron regulation. |

== Mechanism == | == Mechanism == | ||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

From a hard-soft acid-base (HSAB) perspective, this behavior is chemically intuitive. According to HSAB theory, hard acids prefer to bind with hard bases, and soft acids with soft bases.<ref name="Lopachin">Lopachin, R. M., Gavin, T., Decaprio, A., & Barber, D. S. (2012). Application of the Hard and Soft, Acids and Bases (HSAB) theory to toxicant--target interactions. Chemical research in toxicology, 25(2), 239–251. https://doi.org/10.1021/tx2003257</ref> Fe³⁺ is a hard Lewis acid because it is small, highly charged, and not very polarizable. Ferritin’s iron-binding sites are rich in hard base residues such as glutamate and aspartate, which have oxygen donor atoms (hard bases).<ref name="Lopachin" /> This makes the iron-glutamate/aspartate interactions highly favorable, stabilizing Fe³⁺ in the protein’s core. In contrast, Fe²⁺ is a borderline acid and is more reactive, converting it to Fe³⁺ reduces the risk of it catalyzing the harmful Fenton reactions. | From a hard-soft acid-base (HSAB) perspective, this behavior is chemically intuitive. According to HSAB theory, hard acids prefer to bind with hard bases, and soft acids with soft bases.<ref name="Lopachin">Lopachin, R. M., Gavin, T., Decaprio, A., & Barber, D. S. (2012). Application of the Hard and Soft, Acids and Bases (HSAB) theory to toxicant--target interactions. Chemical research in toxicology, 25(2), 239–251. https://doi.org/10.1021/tx2003257</ref> Fe³⁺ is a hard Lewis acid because it is small, highly charged, and not very polarizable. Ferritin’s iron-binding sites are rich in hard base residues such as glutamate and aspartate, which have oxygen donor atoms (hard bases).<ref name="Lopachin" /> This makes the iron-glutamate/aspartate interactions highly favorable, stabilizing Fe³⁺ in the protein’s core. In contrast, Fe²⁺ is a borderline acid and is more reactive, converting it to Fe³⁺ reduces the risk of it catalyzing the harmful Fenton reactions. | ||

| - | Ferritin has a unique way of stabilizing the iron ions as they are transported through its protein shell. Ferritin has known chelator regions on its shell which are used to support selectivity of iron. The chelate effect occurs when a ligand has multiple donor groups for a | + | Ferritin has a unique way of stabilizing the iron ions as they are transported through its protein shell. Ferritin has known chelator regions on its shell which are used to support selectivity of iron. The chelate effect occurs when a ligand has multiple donor groups for a metal ion and has an entropic effect.<ref name="LibreText" /> This means that entropy is increased favorably when the chelator is bound because instead of multiple individual ligands interacting, there is one ligand bound to the metal ion through multiple donor groups. In the case of ferritin and the context of chelation, ferritin is considered a single, polydentate ligand. This means it is a molecule with multiple donor atoms that can simultaneously bind to iron, form multiple bonds, and create a ring-like structure around the metal. |

[[Image: 1-s2.0-S0304416510000954-gr1.jpg]] | [[Image: 1-s2.0-S0304416510000954-gr1.jpg]] | ||

Current revision

Ferritin

| |||||||||||

References

- ↑ Carmona, F., Palacios, Ò., Gálvez, N., Cuesta, R., Atrian, S., Capdevila, M., & Domínguez-Vera, J. M. (n.d.). Ferritin iron uptake and release in the presence of metals and metalloproteins: Chemical implications in the brain.

- ↑ Knovich, M. A.; Storey, J. A.; Coffman, L. G.; Torti, S. V. Ferritin for the Clinician. Blood Rev 2009, 23 (3), 95–104.

- ↑ Bradley, J. M.; Le Brun, N. E.; Moore, G. R. Ferritins: Furnishing Proteins with Iron. JBIC Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry 2016, 21 (1), 13–28.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Srivastava, A.K., Reutovich, A.A., Hunter, N.J. et al. Ferritin microheterogeneity, subunit composition, functional, and physiological implications. Sci Rep 13, 19862 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46880-9

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Levi, S., & Rovida, E. (2015). Neuroferritinopathy: From ferritin structure modification to pathogenetic mechanism. Neurobiology of disease, 81, 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2015.02.007

- ↑ Takahashi, T., & Kuyucak, S. (2003). Functional properties of threefold and fourfold channels in ferritin deduced from electrostatic calculations. Biophysical journal, 84(4), 2256–2263. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75031-0

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 https://chem.libretexts.org/Courses/Duke_University/Textbook%3A_Modern_Applications_of_Chemistry_(Cox)/10%3A_Bioinorganic_Chemistry/10.04%3A_Iron_Storage-_Ferritin

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Lopachin, R. M., Gavin, T., Decaprio, A., & Barber, D. S. (2012). Application of the Hard and Soft, Acids and Bases (HSAB) theory to toxicant--target interactions. Chemical research in toxicology, 25(2), 239–251. https://doi.org/10.1021/tx2003257

- ↑ Bou-Abdallah F. (2010). The iron redox and hydrolysis chemistry of the ferritins. Biochimica et biophysica acta, 1800(8), 719–731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2010.03.021

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Bystrom, L. M., Guzman, M. L., & Rivella, S. (2014). Iron and reactive oxygen species: friends or foes of cancer cells?. Antioxidants & redox signaling, 20(12), 1917–1924. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2012.5014

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Tosha, T., Hasan, M. R., & Theil, E. C. (2008). The ferritin Fe2 site at the diiron catalytic center controls the reaction with O2 in the rapid mineralization pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105(47), 18182–18187. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0805083105

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 https://www.thebloodproject.com/cases-archive/the-abcs-of-ferritin/how-does-iron-get-into-and-out-of-ferritin/#:~:text=Iron%20enters%20ferritin%20through%20pores,lysosomes%20%E2%80%93%20a%20process%20called%20ferritinophagy

- ↑ Wang, J., Wu, N., Peng, M. et al. Ferritinophagy: research advance and clinical significance in cancers. Cell Death Discov. 9, 463 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-023-01753-y

- ↑ Boss, M. A., & Chris Hammel, P. (2012). The role of diffusion in ferritin-induced relaxation enhancement of protons. Journal of magnetic resonance (San Diego, Calif. : 1997), 217, 36–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmr.2012.02.005

- ↑ Kotla, N. K., Dutta, P., Parimi, S., & Das, N. K. (2022). The Role of Ferritin in Health and Disease: Recent Advances and Understandings. Metabolites, 12(7), 609. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo12070609

- ↑ Liu, J. L., Fan, Y. G., Yang, Z. S., Wang, Z. Y., & Guo, C. (2018). Iron and Alzheimer's Disease: From Pathogenesis to Therapeutic Implications. Frontiers in neuroscience, 12, 632. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00632