We apologize for Proteopedia being slow to respond. For the past two years, a new implementation of Proteopedia has been being built. Soon, it will replace this 18-year old system. All existing content will be moved to the new system at a date that will be announced here.

CRISPR-Cas

From Proteopedia

(Difference between revisions)

| Line 100: | Line 100: | ||

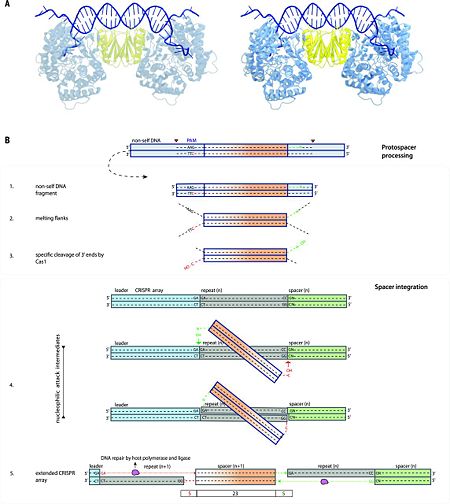

4) Nicking of both strands of the leaderproximal repeat of the CRISPR array at the 5′ ends through a direct nucleophilic attack by the generated 3′ OH groups, resulting in covalent links of each of the strands of the newly selected spacer to the single-stranded repeat ends. | 4) Nicking of both strands of the leaderproximal repeat of the CRISPR array at the 5′ ends through a direct nucleophilic attack by the generated 3′ OH groups, resulting in covalent links of each of the strands of the newly selected spacer to the single-stranded repeat ends. | ||

5) Second-strand synthesis and ligation of the repeat flanks by a non-Cas repair system <ref name="Rev446">doi:10.1038/nrmicro.2015.14</ref><ref name="Rev461">doi:10.1038/nature14237</ref>.<ref name="Rev4">doi:10.1126/science.aad5147</ref> | 5) Second-strand synthesis and ligation of the repeat flanks by a non-Cas repair system <ref name="Rev446">doi:10.1038/nrmicro.2015.14</ref><ref name="Rev461">doi:10.1038/nature14237</ref>.<ref name="Rev4">doi:10.1126/science.aad5147</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Primed spacer adaptation so far has been demonstrated only in type I systems (50, 65, 66). This priming mechanism constitutes a positive feedback loop that facilitates the acquisition of new spacers from formerly encountered genetic elements (67). Priming can occur even with spacers that contain several mismatches, making them incompetent as guides for targeting the cognate foreign DNA (67). Based on PAM selection, functional spacers are preferentially acquired during naïve adaptation. This initial acquisition event triggers a rapid priming response after subsequent infections. Priming appears to be a major pathway of CRISPR adaptation, at least for some type I systems (65). Primed adaptation strongly depends on the spacer sequence (68), and the acquisition efficiency is highest in close proximity to the priming site. In addition, the orientation of newly inserted spacers indicates a strand bias, which is consistentwith the involvement of singlestranded adaption intermediates (69). According to one proposed model (70), replication forks in the invader’s DNA are blocked by the Cascade complex bound to the priming crRNA, enabling the RecG helicase and the Cas3 helicase/nuclease proteins to attack the DNA. The ends at the collapsed forks then could be targeted by RecBCD, which provides DNA fragments for new spacer generation (70). Given that the use of crRNA for priming has much less strict sequence requirements than direct targeting of the invading DNA, priming is a powerful strategy that might have evolved in the course of the host-parasite arms race to reduce the escape by viral mutants, to provide robust resistance against invading DNA, and to enhance self/nonself discrimination. Naïve as well as primed adaptation in the subtype I-F system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa CRISPR-Cas require both the adaptation and the effector module (69). | ||

SEE [[CRISPR-Cas Part II]] | SEE [[CRISPR-Cas Part II]] | ||

Revision as of 09:54, 18 December 2016

| |||||||||||

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Didovyk A, Borek B, Tsimring L, Hasty J. Transcriptional regulation with CRISPR-Cas9: principles, advances, and applications. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2016 Aug;40:177-84. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2016.06.003. Epub, 2016 Jun 23. PMID:27344519 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2016.06.003

- ↑ Brophy JA, Voigt CA. Principles of genetic circuit design. Nat Methods. 2014 May;11(5):508-20. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2926. PMID:24781324 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2926

- ↑ Straubeta A, Lahaye T. Zinc fingers, TAL effectors, or Cas9-based DNA binding proteins: what's best for targeting desired genome loci? Mol Plant. 2013 Sep;6(5):1384-7. doi: 10.1093/mp/sst075. Epub 2013 May 29. PMID:23718948 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/mp/sst075

- ↑ Sander JD, Joung JK. CRISPR-Cas systems for editing, regulating and targeting genomes. Nat Biotechnol. 2014 Apr;32(4):347-55. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2842. Epub 2014 Mar 2. PMID:24584096 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2842

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Hochstrasser ML, Doudna JA. Cutting it close: CRISPR-associated endoribonuclease structure and function. Trends Biochem Sci. 2015 Jan;40(1):58-66. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.10.007. Epub, 2014 Nov 18. PMID:25468820 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2014.10.007

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Barrangou R, Fremaux C, Deveau H, Richards M, Boyaval P, Moineau S, Romero DA, Horvath P. CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science. 2007 Mar 23;315(5819):1709-12. PMID:17379808 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1138140

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 7.18 Mohanraju P, Makarova KS, Zetsche B, Zhang F, Koonin EV, van der Oost J. Diverse evolutionary roots and mechanistic variations of the CRISPR-Cas systems. Science. 2016 Aug 5;353(6299):aad5147. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5147. PMID:27493190 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.aad5147

- ↑ Kunin V, Sorek R, Hugenholtz P. Evolutionary conservation of sequence and secondary structures in CRISPR repeats. Genome Biol. 2007;8(4):R61. PMID:17442114 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/gb-2007-8-4-r61

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Brouns SJ, Jore MM, Lundgren M, Westra ER, Slijkhuis RJ, Snijders AP, Dickman MJ, Makarova KS, Koonin EV, van der Oost J. Small CRISPR RNAs guide antiviral defense in prokaryotes. Science. 2008 Aug 15;321(5891):960-4. doi: 10.1126/science.1159689. PMID:18703739 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1159689

- ↑ Garneau JE, Dupuis ME, Villion M, Romero DA, Barrangou R, Boyaval P, Fremaux C, Horvath P, Magadan AH, Moineau S. The CRISPR/Cas bacterial immune system cleaves bacteriophage and plasmid DNA. Nature. 2010 Nov 4;468(7320):67-71. doi: 10.1038/nature09523. PMID:21048762 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature09523

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Alkhnbashi OS, Costa F, Shah SA, Saunders SJ, Barrangou R, Brouns SJ, Charpentier E, Haft DH, Horvath P, Moineau S, Mojica FJ, Terns RM, Terns MP, White MF, Yakunin AF, Garrett RA, van der Oost J, Backofen R, Koonin EV. An updated evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015 Nov;13(11):722-36. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3569. Epub 2015, Sep 28. PMID:26411297 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro3569

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 12.8 Shmakov S, Abudayyeh OO, Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Gootenberg JS, Semenova E, Minakhin L, Joung J, Konermann S, Severinov K, Zhang F, Koonin EV. Discovery and Functional Characterization of Diverse Class 2 CRISPR-Cas Systems. Mol Cell. 2015 Nov 5;60(3):385-97. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.008. Epub 2015, Oct 22. PMID:26593719 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.008

- ↑ Jiang F, Zhou K, Ma L, Gressel S, Doudna JA. STRUCTURAL BIOLOGY. A Cas9-guide RNA complex preorganized for target DNA recognition. Science. 2015 Jun 26;348(6242):1477-81. doi: 10.1126/science.aab1452. PMID:26113724 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.aab1452

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012 Aug 17;337(6096):816-21. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. Epub 2012, Jun 28. PMID:22745249 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1225829

- ↑ Gasiunas G, Barrangou R, Horvath P, Siksnys V. Cas9-crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex mediates specific DNA cleavage for adaptive immunity in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 Sep 25;109(39):E2579-86. Epub 2012 Sep 4. PMID:22949671 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1208507109

- ↑ Qi LS, Larson MH, Gilbert LA, Doudna JA, Weissman JS, Arkin AP, Lim WA. Repurposing CRISPR as an RNA-guided platform for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Cell. 2013 Feb 28;152(5):1173-83. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.022. PMID:23452860 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.022

- ↑ Bikard D, Jiang W, Samai P, Hochschild A, Zhang F, Marraffini LA. Programmable repression and activation of bacterial gene expression using an engineered CRISPR-Cas system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013 Aug;41(15):7429-37. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt520. Epub 2013, Jun 12. PMID:23761437 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkt520

- ↑ Kuscu C, Arslan S, Singh R, Thorpe J, Adli M. Genome-wide analysis reveals characteristics of off-target sites bound by the Cas9 endonuclease. Nat Biotechnol. 2014 Jul;32(7):677-83. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2916. Epub 2014 May 18. PMID:24837660 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2916

- ↑ Krupovic M, Makarova KS, Forterre P, Prangishvili D, Koonin EV. Casposons: a new superfamily of self-synthesizing DNA transposons at the origin of prokaryotic CRISPR-Cas immunity. BMC Biol. 2014 May 19;12:36. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-12-36. PMID:24884953 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1741-7007-12-36

- ↑ Stern A, Keren L, Wurtzel O, Amitai G, Sorek R. Self-targeting by CRISPR: gene regulation or autoimmunity? Trends Genet. 2010 Aug;26(8):335-40. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2010.05.008. Epub 2010, Jul 1. PMID:20598393 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2010.05.008

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 Yosef I, Goren MG, Qimron U. Proteins and DNA elements essential for the CRISPR adaptation process in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012 Jul;40(12):5569-76. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks216. Epub 2012, Mar 8. PMID:22402487 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks216

- ↑ Wei Y, Terns RM, Terns MP. Cas9 function and host genome sampling in Type II-A CRISPR-Cas adaptation. Genes Dev. 2015 Feb 15;29(4):356-61. doi: 10.1101/gad.257550.114. PMID:25691466 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.257550.114

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Levy A, Goren MG, Yosef I, Auster O, Manor M, Amitai G, Edgar R, Qimron U, Sorek R. CRISPR adaptation biases explain preference for acquisition of foreign DNA. Nature. 2015 Apr 23;520(7548):505-10. doi: 10.1038/nature14302. Epub 2015 Apr 13. PMID:25874675 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature14302

- ↑ Erdmann S, Le Moine Bauer S, Garrett RA. Inter-viral conflicts that exploit host CRISPR immune systems of Sulfolobus. Mol Microbiol. 2014 Mar;91(5):900-17. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12503. Epub 2014 Jan 17. PMID:24433295 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/mmi.12503

- ↑ Wigley DB. RecBCD: the supercar of DNA repair. Cell. 2007 Nov 16;131(4):651-3. PMID:18022359 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.004

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Dupuis ME, Villion M, Magadan AH, Moineau S. CRISPR-Cas and restriction-modification systems are compatible and increase phage resistance. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2087. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3087. PMID:23820428 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3087

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Swarts DC, Mosterd C, van Passel MW, Brouns SJ. CRISPR interference directs strand specific spacer acquisition. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035888. Epub 2012 Apr 27. PMID:22558257 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035888

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Nunez JK, Kranzusch PJ, Noeske J, Wright AV, Davies CW, Doudna JA. Cas1-Cas2 complex formation mediates spacer acquisition during CRISPR-Cas adaptive immunity. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014 May 4. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2820. PMID:24793649 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.2820

- ↑ Wang J, Li J, Zhao H, Sheng G, Wang M, Yin M, Wang Y. Structural and Mechanistic Basis of PAM-Dependent Spacer Acquisition in CRISPR-Cas Systems. Cell. 2015 Nov 5;163(4):840-53. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.008. Epub 2015 Oct, 17. PMID:26478180 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.008

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Nunez JK, Lee AS, Engelman A, Doudna JA. Integrase-mediated spacer acquisition during CRISPR-Cas adaptive immunity. Nature. 2015 Mar 12;519(7542):193-8. doi: 10.1038/nature14237. Epub 2015 Feb 18. PMID:25707795 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature14237

- ↑ van der Oost J, Jore MM, Westra ER, Lundgren M, Brouns SJ. CRISPR-based adaptive and heritable immunity in prokaryotes. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009 Aug;34(8):401-7. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.05.002. Epub, 2009 Jul 29. PMID:19646880 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2009.05.002

- ↑ Silas S, Mohr G, Sidote DJ, Markham LM, Sanchez-Amat A, Bhaya D, Lambowitz AM, Fire AZ. Direct CRISPR spacer acquisition from RNA by a natural reverse transcriptase-Cas1 fusion protein. Science. 2016 Feb 26;351(6276):aad4234. doi: 10.1126/science.aad4234. PMID:26917774 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.aad4234

- ↑ Fineran PC, Charpentier E. Memory of viral infections by CRISPR-Cas adaptive immune systems: acquisition of new information. Virology. 2012 Dec 20;434(2):202-9. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.10.003. Epub 2012, Nov 2. PMID:23123013 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2012.10.003

- ↑ Arslan Z, Hermanns V, Wurm R, Wagner R, Pul U. Detection and characterization of spacer integration intermediates in type I-E CRISPR-Cas system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014 Jul;42(12):7884-93. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku510. Epub 2014, Jun 11. PMID:24920831 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gku510

- ↑ Amitai G, Sorek R. CRISPR-Cas adaptation: insights into the mechanism of action. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016 Feb;14(2):67-76. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2015.14. Epub 2016 , Jan 11. PMID:26751509 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2015.14

Categories: Topic Page | Crispr | Crispr-associated | Endonuclease | Cas9 | Cas6

![Fig. 1 Overview of the CRISPR-Cas systems. (A) Architecture of class 1 (multiprotein effector complexes) and class 2 (single-protein effector complexes) CRISPR-Cas systems. (B) CRISPR-Cas adaptive immunity is mediated by CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs) and Cas proteins, which form multicomponent CRISPR ribonucleoprotein (crRNP) complexes. The first stage is adaptation, which occurs upon entry of an invading mobile genetic element (in this case, a viral genome). Cas1 (blue) and Cas2 (yellow) proteins select and process the invading DNA, and thereafter, a protospacer (orange) is integrated as a new spacer at the leader end of the CRISPR array [repeat sequences (gray) that separate similar-sized, invader-derived spacers (multiple colors)]. During the second stage, expression, the CRISPR locus is transcribed and the pre-crRNA is processed into mature crRNA guides by Cas (e.g., Cas6) or non-Cas proteins (e.g., RNase III). During the final interference stage, the Cas-crRNA complex scans invading DNA for a complementary nucleic acid target, after which the target is degraded by a Cas nuclease. From](/wiki/images/thumb/f/f2/F1r.jpg/450px-F1r.jpg)