User:Natalie Van Ochten/Sandbox 1

From Proteopedia

(Difference between revisions)

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

==Different Isoforms== | ==Different Isoforms== | ||

| - | DDAH has two main isoforms <ref name="frey" />. DDAH-1 colocalizes with nNOS (neuronal NOS). This enzyme is found mainly in the brain and kidneys of organisms <ref name="tran" />. DDAH-2 is found in tissues with eNOS (endothelial NOS) <ref name="frey" />. DDAH-2 localization has been found in the heart, kidney, and placenta <ref name="tran" />. Additionally, studies show that DDAH-2 is expressed in iNOS containing immune tissues (inducible NOS) <ref name="frey" />. Both of the isoforms have conserved residues that are involved in the catalytic mechanism of DDAH (Cys, Asp, and His). The differences between the isoforms is in the substrate binding residues and the lid region residues. DDAH-1 has a positively charged lid region while DDAH-2 has a negatively charged lid. In total, three salt bridge differ between DDAH-1 and DDAH-2 isoforms <ref name="frey" />. | + | DDAH has two main isoforms <ref name="frey" />. DDAH-1 colocalizes with <span class="plainlinks">[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nitric_oxide_synthase nNOS (neuronal NOS)]</span>. This enzyme is found mainly in the brain and kidneys of organisms <ref name="tran" />. DDAH-2 is found in tissues with <span class="plainlinks">[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nitric_oxide_synthase eNOS (endothelial NOS)]</span> <ref name="frey" />. DDAH-2 localization has been found in the heart, kidney, and placenta <ref name="tran" />. Additionally, studies show that DDAH-2 is expressed in iNOS containing immune tissues <span class="plainlinks">[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nitric_oxide_synthase (inducible NOS)]</span> <ref name="frey" />. Both of the isoforms have conserved residues that are involved in the catalytic mechanism of DDAH (Cys, Asp, and His). The differences between the isoforms is in the substrate binding residues and the lid region residues. DDAH-1 has a positively charged lid region while DDAH-2 has a negatively charged lid. In total, three salt bridge differ between DDAH-1 and DDAH-2 isoforms <ref name="frey" />. |

==General Structure== | ==General Structure== | ||

| - | DDAH-1’s <scene name='69/694225/Secondary_structure_colored/3'>secondary structure</scene> has a <scene name='69/694225/Prop_domains/2'>propeller-like fold</scene> which is characteristic of the superfamily of <span class="plainlinks">[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arginine:glycine_amidinotransferase L-arginine/glycine amidinotransferases]</span> <ref name="humm">Humm A, Fritsche E, Mann K, Göhl M, Huber R. Recombinant expression and isolation of human L-arginine:glycine amidinotransferase and identification of its active-site cysteine residue. Biochemical Journal. 1997 March 15;322(3):771-776. PMID:<span class="plainlinks">[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1218254/ 9148748]</span> doi:<span class="plainlinks">[http://www.biochemj.org/content/322/3/771 10.1042/bj3220771]</span></ref>. This five-stranded <span class="plainlinks">[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beta-propeller propeller]</span> contains five repeats of a ββαβ motif <ref name="frey" />. These motifs in DDAH form a <scene name='75/752351/Ddah_water_pore/12'>channel</scene> filled with water molecules (red spheres). Lys174 and Glu77 form a <scene name='75/752351/Ddah_salt_bridge/5'>salt bridge</scene> in the channel that | + | DDAH-1’s <scene name='69/694225/Secondary_structure_colored/3'>secondary structure</scene> has a <scene name='69/694225/Prop_domains/2'>propeller-like fold</scene> which is characteristic of the superfamily of <span class="plainlinks">[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arginine:glycine_amidinotransferase L-arginine/glycine amidinotransferases]</span> <ref name="humm">Humm A, Fritsche E, Mann K, Göhl M, Huber R. Recombinant expression and isolation of human L-arginine:glycine amidinotransferase and identification of its active-site cysteine residue. Biochemical Journal. 1997 March 15;322(3):771-776. PMID:<span class="plainlinks">[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1218254/ 9148748]</span> doi:<span class="plainlinks">[http://www.biochemj.org/content/322/3/771 10.1042/bj3220771]</span></ref>. This five-stranded <span class="plainlinks">[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beta-propeller propeller]</span> contains five repeats of a ββαβ motif <ref name="frey" />. These motifs in DDAH form a <scene name='75/752351/Ddah_water_pore/12'>channel</scene> filled with water molecules (red spheres). Lys174 and Glu77 form a <scene name='75/752351/Ddah_salt_bridge/5'>salt bridge</scene> in the channel that makes up the bottom of the <scene name='75/752351/Ddah_active_site/3'>active site</scene>, shown here filled with water molecules. One side of the channel is a <scene name='75/752351/Ddah_water_pore/13'>water-filled pore</scene>, whereas the other side is the active site cleft <ref name="frey" />. |

===Lid Region=== | ===Lid Region=== | ||

Amino acids 25-36 of DDAH constitute the flexible | Amino acids 25-36 of DDAH constitute the flexible | ||

| - | <scene name='75/752351/Lid_focus/2'>loop region</scene> of the protein, which is more commonly known as the lid region <ref name="frey" /> | + | <scene name='75/752351/Lid_focus/2'>loop region</scene> of the protein, which is more commonly known as the lid region <ref name="frey" />. Studies have shown crystal structures of the lid at <scene name='69/694225/Open_surface/8'>open</scene> and <scene name='69/694225/Closed_surface/5'>closed</scene> conformations. In the open conformation, the lid forms an <scene name='69/694225/Lid_helix/2'>alpha helix</scene> and the amino acid Leu29 is moved so it does not interact with the active site, thus allowing the active site to be vulnerable to attack. When the lid is closed, a <scene name='75/752351/Hbond_leu29/3'>hydrogen bond</scene> can form between the Leu29 carbonyl and the amino group on a bound molecule. This hydrogen bond stabilizes the substrate in the active site. The Leu29 is then <scene name='75/752351/Hbond_leu29/5'>blocking</scene> the active site entrance <ref name="frey" />. Opening and closing the lid takes place faster than the actual reaction in the active site <ref name="rasheed">Rasheed M, Richter C, Chisty LT, Kirkpatrick J, Blackledge M, Webb MR, Driscoll PC. Ligand-dependent dynamics of the active site lid in bacterial Dimethyarginine Dimethylaminohydrolase. Biochemistry. 2014 Feb 18;53:1092-1104. PMCID:<span class="plainlinks">[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3945819/ PMC3945819]</span> doi:<span class="plainlinks">[http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/bi4015924 10.1021/bi4015924]</span></ref>. This suggests that the <span class="plainlinks">[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rate-determining_step rate-limiting step]</span> of this reaction is not the lid movement, but is the actual chemistry happening to the substrate in the active site of DDAH <ref name="rasheed" />. |

====Lid Region Conservation==== | ====Lid Region Conservation==== | ||

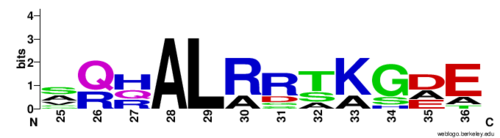

| - | The specific residues in the lid region | + | The specific residues in the lid region vary between organisms <ref name="frey" /> (Figure 2). The only consistent similarity is a <span class="plainlinks">[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conserved_sequence conserved]</span> leucine residue in this lid that functions to hydrogen bond with the <span class="plainlinks">[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ligand ligand]</span> bound to the active site in DDAH-1 but not in DDAH-2 <ref name="rasheed" /> (Figure 2). Different <span class="plainlinks">[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Protein_isoform isoforms]</span> from the same species can have differences in lid regions as well <ref name="frey" />. DDAH-2 has a negatively charged lid while DDAH-1 has a positively charged lid <ref name="frey" />. |

[[Image:Lid Region WebLogo.png|500 px|center|thumb|'''Figure 2.''' WebLogo for the lid region in DDAH-1 of eight different organisms.]] | [[Image:Lid Region WebLogo.png|500 px|center|thumb|'''Figure 2.''' WebLogo for the lid region in DDAH-1 of eight different organisms.]] | ||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

==Clinical Relevance== | ==Clinical Relevance== | ||

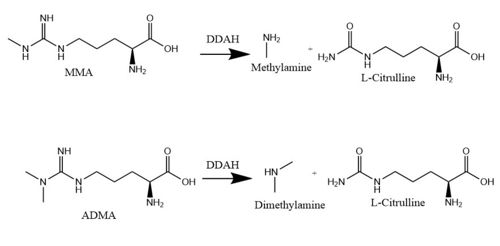

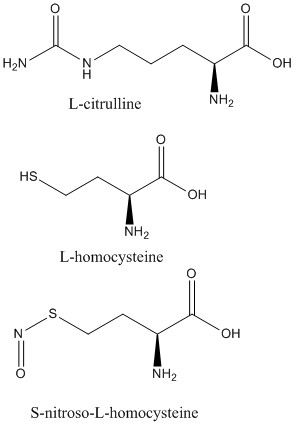

| - | DDAH works to hydrolyze MMA and ADMA <ref name="frey" />. Both MMA and ADMA competitively inhibit NO synthesis by inhibiting Nitric Oxide Synthase (NOS). NO is made by NOS creating L-citrulline from <span class="plainlinks">[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arginine L-arginine]</span> <ref name="frey" />. If DDAH is overexpressed, NOS can be activated <ref name="frey" />. ADMA and MMA can <span class="plainlinks">[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enzyme_inhibitor inhibit]</span> the synthesis of NO by competitively inhibiting all three kinds of | + | DDAH works to hydrolyze MMA and ADMA <ref name="frey" />. Both MMA and ADMA competitively inhibit NO synthesis by inhibiting Nitric Oxide Synthase (NOS). NO is made by NOS creating L-citrulline from <span class="plainlinks">[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arginine L-arginine]</span> <ref name="frey" />. If DDAH is overexpressed, NOS can be activated <ref name="frey" />. ADMA and MMA can <span class="plainlinks">[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enzyme_inhibitor inhibit]</span> the synthesis of NO by competitively inhibiting all three kinds of NOS (endothelial, neuronal, and inducible) <ref name="frey" />. Underexpression or inhibition of DDAH decreases NOS activity and NO levels will decrease. Because of <span class="plainlinks">[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nitric_oxide nitric oxide’s (NO)]</span> role in signaling and defense, NO levels in an organism must be regulated to reduce damage to cells <ref name="janssen">Janssen W, Pullamsetti SS, Cooke J, Weissmann N, Guenther A, Schermuly RT. The role of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH) in pulmonary fibrosis. The Journal of Pathology. 2012 Dec 12;229(2):242-249. Epub 2013 Jan. PMID:<span class="plainlinks">[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23097221 23097221]</span> doi:<span class="plainlinks">[http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/path.4127/references;jsessionid=C34C6C633A21C2ECE14278BBC902AD71.f03t04?globalMessage=0 10.1002/path.4127]</span></ref>. NO is an important signaling and effector molecule in <span class="plainlinks">[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neurotransmission neurotransmission]</span>, bacterial defense, and regulation of vascular tone <ref name="colasanti">Colasanti M, Suzuki H. The dual personality of NO. ScienceDirect. 2000 Jul 1;21(7):249-252. PMID:<span class="plainlinks">[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10979862 10979862]</span> doi:<span class="plainlinks">[http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165614700014991 10.1016/S0165-6147(00)01499-1]</span></ref>. Because NO is highly toxic, freely diffusible across membranes, and its radical form is fairly reactive, cells must maintain a large control on concentrations by regulating NOS activity and the activity of enzymes such as DDAH that have an indirect effect of the concentration of NO <ref name="rassaf">Rassaf T, Feelisch M, Kelm M. Circulating NO pool: assessment of nitrite and nitroso species in blood and tissues. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 2004 Feb 15;36(4):413-422. PMID:<span class="plainlinks">[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14975444 14975444]</span> doi:<span class="plainlinks">[http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0891584903007962 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.11.011]</span></ref>. An imbalance of NO contributes to several diseases. Low NO levels, potentially caused by low DDAH activity and therefore high MMA and ADMA concentrations, have been implicated with diseases such as <span class="plainlinks">[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uremia uremia]</span>, <span class="plainlinks">[http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heart-failure/basics/definition/con-20029801 chronic heart failure]</span>, <span class="plainlinks">[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atherosclerosis atherosclerosis]</span>, and <span class="plainlinks">[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hyperhomocysteinemia hyperhomocysteinemia]</span> <ref name="tsao">Tsao PS, Cooke JP. Endothelial alterations in hypercholesterolemia: more than simply vasodilator dysfunction. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 1998;32(3):48-53. PMID:<span class="plainlinks">[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9883748 9883748]</span></ref>. High levels of NO have been involved with diseases such as <span class="plainlinks">[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Septic_shock septic shock]</span>, <span class="plainlinks">[http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/migraine-headache/home/ovc-20202432 migraine]</span>, <span class="plainlinks">[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inflammation inflammation]</span>, and <span class="plainlinks">[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neurodegeneration neurodegenerative disorders]</span> <ref name="vallance">Vallance P, Leiper J. Blocking NO synthesis: how, where and why? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2002 Dec;1(12):939-950. PMID:<span class="plainlinks">[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12461516 12461516]</span> doi:<span class="plainlinks">[http://www.nature.com/nrd/journal/v1/n12/full/nrd960.html 10.1038/nrd960]</span></ref>. Because of the effects on NO levels and known inhibitors to DDAH, regulation of DDAH may be an effective way to regulate NO levels, therefore treating these diseases <ref name="frey" />. Additionally, researchers can take advantage of the fact that there are two different isoforms of this enzyme and create drugs that target one isoform over another to control NO levels in specific tissues in the body <ref name="frey" />. |

</StructureSection> | </StructureSection> | ||

Revision as of 17:46, 21 April 2017

Dimethylarginine Dimethylaminohydrolase

| |||||||||||

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Palm F, Onozato ML, Luo Z, Wilcox CS. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH): expression, regulation, and function in the cardiovascular and renal systems. American Journal of Physiology. 2007 Dec 1;293(6):3227-3245. PMID:17933965 doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00998.2007

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Tran CTL, Leiper JM, Vallance P. The DDAH/ADMA/NOS pathway. Atherosclerosis Supplements. 2003 Dec;4(4):33-40. PMID:14664901 doi:10.1016/S1567-5688(03)00032-1

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 3.22 3.23 3.24 Frey D, Braun O, Briand C, Vasak M, Grutter MG. Structure of the mammalian NOS regulator dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase: a basis for the design of specific inhibitors. Structure. 2006 May;14(5):901-911. PMID:[1] doi:10.1016/j.str.2006.03.006

- ↑ Humm A, Fritsche E, Mann K, Göhl M, Huber R. Recombinant expression and isolation of human L-arginine:glycine amidinotransferase and identification of its active-site cysteine residue. Biochemical Journal. 1997 March 15;322(3):771-776. PMID:9148748 doi:10.1042/bj3220771

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Rasheed M, Richter C, Chisty LT, Kirkpatrick J, Blackledge M, Webb MR, Driscoll PC. Ligand-dependent dynamics of the active site lid in bacterial Dimethyarginine Dimethylaminohydrolase. Biochemistry. 2014 Feb 18;53:1092-1104. PMCID:PMC3945819 doi:10.1021/bi4015924

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Stone EM, Costello AL, Tierney DL, Fast W. Substrate-assisted cysteine deprotonation in the mechanism of Dimethylargininase (DDAH) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochemistry. 2006 May 2;45(17):5618-5630. PMID:16634643 doi:10.1021/bi052595m

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Pace NJ, Weerpana E. Zinc-binding cysteines: diverse functions and structural motifs. Biomolecules. 2014 June;4(2):419-434. PMCID:4101490 doi:10.3390/biom4020419

- ↑ Janssen W, Pullamsetti SS, Cooke J, Weissmann N, Guenther A, Schermuly RT. The role of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH) in pulmonary fibrosis. The Journal of Pathology. 2012 Dec 12;229(2):242-249. Epub 2013 Jan. PMID:23097221 doi:10.1002/path.4127

- ↑ Colasanti M, Suzuki H. The dual personality of NO. ScienceDirect. 2000 Jul 1;21(7):249-252. PMID:10979862 doi:10.1016/S0165-6147(00)01499-1

- ↑ Rassaf T, Feelisch M, Kelm M. Circulating NO pool: assessment of nitrite and nitroso species in blood and tissues. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 2004 Feb 15;36(4):413-422. PMID:14975444 doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.11.011

- ↑ Tsao PS, Cooke JP. Endothelial alterations in hypercholesterolemia: more than simply vasodilator dysfunction. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 1998;32(3):48-53. PMID:9883748

- ↑ Vallance P, Leiper J. Blocking NO synthesis: how, where and why? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2002 Dec;1(12):939-950. PMID:12461516 doi:10.1038/nrd960

Student Contributors

- Natalie Van Ochten

- Kaitlyn Enderle

- Colton Junod

3D Structures of Dimethylarginine Dimethylaminohydrolase

2C6Z L-citrulline bound to isoform 1

2CI1 S-nitroso-L-homocysteine bound to isoform 1

2CI3 crystal form 1

2CI4 crystal form 2

2CI5 L-homocysteine bound to isoform 1

2CI6 Zn (II) bound at low pH to isoform 1

2CI7 Zn (II) bound at high pH to isoform 1