User:Ethan Kitt/Sandbox 1

From Proteopedia

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

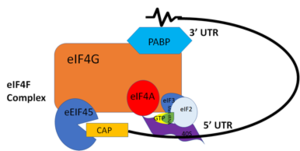

In more complex eukaryotic organisms, PABP indirectly stimulates translation via [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PAIP1 PAIP-1] (PABP interacting protein). A higher presence of PAIP-1 increases the rate of translation initiation, indicating another way to “close the loop.”¹ | In more complex eukaryotic organisms, PABP indirectly stimulates translation via [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PAIP1 PAIP-1] (PABP interacting protein). A higher presence of PAIP-1 increases the rate of translation initiation, indicating another way to “close the loop.”¹ | ||

| - | + | </StructureSection> | |

==Disease and Medical Relevance== | ==Disease and Medical Relevance== | ||

Revision as of 18:24, 20 April 2018

Contents |

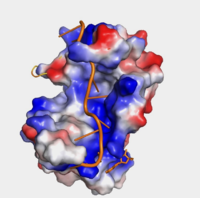

Human Poly(A) Binding Protein (1CVJ)

Background

The Human Poly(A) Binding Protein (PABP) was discovered in 1973 by the use of a sedimentation profile detailing the RNase digestion differentiated the PABP protein. [1] Attempts to purify the 75 kDa protein then followed. In 1983, then considered “poly(A)-organizing protein,” was determined and purified by molecular weight, ligand-binding affinity, and amounts found in cytoplasmic portions of cell with ability to bind to free poly(A). [2]

Structure

| |||||||||||

Disease and Medical Relevance

Oculopharyngeal Muscular Dystrophy

Oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy, or OPMD, is an autosomal dominant late-onset disease. [7] It’s characterized by the myopathy of the eyelids and the throat. The symptoms entail eye-drooping and difficulty swallowing. There are two types of OPMD: autosomal dominant and recessive, both originating from the mutation of the PABP nuclear 1 (PABPN1) gene located on the long arm of chromosome 14. [7] This mutation results in an abnormally long polyalanine tract, 11-18 alanines, opposed to the normal 10. [7] Patients with longer PABPN1 expansion (more alanines) are on average diagnosed at an earlier in life than patients with a shorter expansion; therefore, expansion size plays a role in OPMD severity and progression. [8]

The mutation results in PABPN1 forming clumps in muscle cells that can’t be degraded. [7] It’s suspected that this is a source of cell death for effected cells, however, it has not been concluded why this mutation only affects certain muscle cells.

Studies on Mutations

Studies conducted on Drosophila are common due to 75% conservation between human and Drosophila genomes. Drosophila only encode one cytoplasmic PABP, and its deletion results in embryonic lethality. [6] Similarly, in Caenorhabditis elegans, which have two cytoplasmic PABPs, display 50-80% embryonic lethality with the introduction of an RNAi to one of these PABPs. [6]

References

- ↑ Blobel, Gunter. “A Protein of Molecular Weight 78,000 Bound to the Polyadenylate Region of Eukaryotic Messenger Rnas.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 70, no. 3, 1973, pp. 924–8.

- ↑ Baer, Bradford W. and Kornberg, Roger D. "The Protein Responsible for the Repeating Structure of Cytoplasmic Poly(A)-Ribonucleoprotein." The Journal of Cell Biology, vol. 96, no. 3, Mar. 1983, pp. 717-721. EBSCOhost.

- ↑ Kühn, Uwe and Elmar, Wahle. “Structure and Function of Poly(a) Binding Proteins.” Bba - Gene Structure & Expression, vol. 1678, no. 2/3, 2004.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Deo, Rahul C, et al. “Recognition of Polyadenylate RNA by the Poly(A)-Binding Protein.” Cell 98:6. (1999) 835-845. Print.

- ↑ Wang, Zuoren and Kiledjian, Megerditch. “The Poly(A)-Binding Protein and an mRNA Stability Protein Jointly Regulate an Endoribonuclease Activity.” Molecular and Cellular Biology 20.17 (2000): 6334–6341. Print.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Gorgoni, Barbra, and Gray, Nicola. “The Roles of Cytoplasmic Poly(A)-Binding Proteins in Regulating Gene Expression: A Developmental Perspective.” Briefings in Functional Genomics and Proteomics, vol. 3, no. 2, 1 Aug. 2004, pp. 125–141., doi:10.1093/bfgp/3.2.125.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 “Oculopharyngeal Muscular Dystrophy.” NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders), rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/oculopharyngeal-muscular-dystrophy/.

- ↑ Richard, Pascale, et al. “Correlation between PABPN1 Genotype and Disease Severity in Oculopharyngeal Muscular Dystrophy.” Neurology, vol. 88, no. 4, 2016, pp. 359–365., doi:10.1212/wnl.0000000000003554.