Introduction

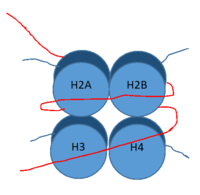

Figure 1: DNA (red) wrapped around histone proteins with histone tails (blue)

LSD-1 is a lysine demethylase. A histone is a blah blah blah and can be seen in Fig. 1.

Structure

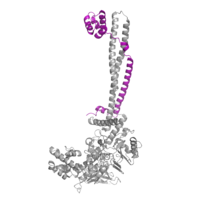

Figure 2: LSD1 overall 3D structure: Tower domain (blue), SWIRM domain (yellow), and Oxidase domain (red).

Tower Domain

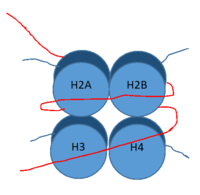

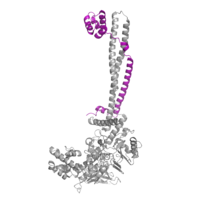

Figure 3: CoRest complex (purple) bound to LSD1 at the Tower domain.

The is a 100 residue protrusion off of the main protein body of LSD-1, comprised of 2 𝛂-helices. The longer helix, T𝛂A, is an LSD-1 specific element that has not been found in any other oxidase proteins [1]. The shorter helix, T𝛂B, is very near to the active site of the oxidase domain. In fact, T𝛂B connects directly to helix 𝛂D of the oxidase domain through a highly conserved connector loop. The exact function of the tower domain is not known, but it is proposed to regulate the size of the active site chamber through this . The T𝛂B-𝛂D interaction is responsible for the proper positioning of , a side chain of 𝛂D that is located in the catalytic chamber. In addition, the T𝛂B-𝛂D interaction positions 𝛂D in the correct manner to provide hydrogen bonding to . Tyr761 is positioned in the catalytic chamber very close to the FAD cofactor, and aids in the binding of the lysine substrate [1]. Therefore, the base of the tower domain forms a direct connection to the oxidase domain and plays a crucial role in the shape and catalytic activity of the active site. In fact, removing the tower domain via a mutation resulted in a drastic decrease in catalytic efficiency [1]. The tower domain has also been found to interact with other proteins and complexes, such as CoREST (Figure 3), as a molecular lever to allosterically regulate the catalytic activity of the active site [2]. Overall, the exact function of the tower domain has not yet been determined, but it is known to be vital to the catalytic activity of LSD-1.

SWIRM Domain

Oxidase Domain

The is responsible for housing the site of catalytic activity in LSD-1. The domain has two distinct subunits: one non-covalently binds the FAD cofactor and the other acts in both the binding and recognition of the substrate lysine on a histone tail(H3)[1]. The active site cavity is placed within the substrate-binding subunit of the oxidase domain and is unique due to its great size. In relation to other FAD-dependent oxidases, LSD-1 has an immense active site cavity that is 15 Å deep and 25 Å at its widest opening [1]. In comparison, polyamine oxidase, another FAD-dependent oxidase, has a catalytic chamber roughly 30 Å long but only a few angstroms wide [3]. The relatively large size of the LSD-1 active site cavity suggests that additional residues, in addition to the substrate lysine, enter into the active site during catalysis. These additional residues could participate in substrate recognition and may contribute to the enzyme’s specificity for H3K4 and H3K9.

Active Site and FAD Cofactor

Within the active site cavity, there are four invaginations, or , each with differing chemical properties. The first pocket or invagination within the active site (residues Val317, Gly330, Ala331, Met332, Val333, Phe538, Leu659, Asn660, Lys661, Trp695, Ser749, Ser760 and Tyr761) catalyzes the interaction between the FAD cofactor and the substrate lysine [1]. This first pocket binds and positions the substrate lysine so that it is exposed to the . During catalysis, the FAD cofactor is reduced and becomes an anion. Therefore, a positively charged residue is present in most FAD-dependent oxidases to assist in stabilizing the anionic form of FAD. is present in the catalytic pocket of the active site to stabilize the negatively charged FAD [1]. The other three are not as well understood but predictions can be made about their functions within the active site of LSD-1. Because the active site is able to accept additional residues on the substrate histone other than the lysine, the remaining three pockets are most plausibly responsible for the recognition of chemical modifications on the histone itself [1]. The first pocket (Pocket 1) that assists in recognizing chemical modifications on the substrate histone is composed of residues Val334, Thr335, Asn340, Met342, Tyr571, Thr810, Val811 and His812 [1]. The second pocket in the active site for side-chain recognition (Pocket 2) is composed of Phe558, Glu559, Phe560, Asn806, Tyr807 and Pro808 [1]. Pocket 3 within the active site is composed of Asn540, Leu547, Trp552, Asp553, Gln554, Asp555, Asp556, Ser762, Tyr763, Val764 and Tyr773 [1]. Each of the three pockets, in addition to the catalytic pocket, are able to recognize distinct modifications on the substrate and contribute to the specificity of LSD-1.

Mechanism of Action

Figure 4: Hydride transfer mechanism of LSD-1 active site via FAD cofactor.

The mechanism of lysine demethylation is highly dependent on the presence of the . The FAD cofactor, positioned closely to the substrate lysine in the active site, acts as an oxidizing agent and initiates catalysis (Figure 4). A two-electron transfer occurs between the substrate lysine and FAD in the form of a hydride; the lysine is oxidized and the FAD is reduced [1]. The FAD cofactor forms an anion and is stabilized by the positively charged positioned in the catalytic pocket of the active site [1]. Although Lys661 is 8 Å away from the nitrogen in FAD that is thought to sustain the negative charge in its reduced form, through resonance it is possible that the negative charge may be dispersed to an atom closer to the stabilizing Lys661. The oxidized lysine forms an aminium cation that is hydrolyzed into the carbinolamine intermediate [1]. The carbinolamine intermediate readily decomposes into formaldehyde and the demethylated lysine substrate [1].

Inhibition by Tri-Methylated Lysine

Figure 5: Structure of Tri-methylated lysine, which chemically inhibits LSD-1 activity.

The proposed LSD-1 mechanism is supported by the fact that tri-methylated lysine substrates (Figure 5) competitively inhibit the enzyme. A substrate lysine that is tri-methylated binds to the active site but does not undergo catalysis; the inhibition is not steric (the active site is large enough to accommodate tri-methylated lysines), but is rather chemical in nature. Tri-methylated lysines do not have a free hydrogen to lose in a hydride transfer as is necessitated by the proposed mechanism, resulting in chemical inhibition of LSD-1 [1]. Thus, the mechanism of LSD-1 contributes to its specificity for mono- or di-methylated lysine substrates.

Medical Implications

Knowledge about LSD-1 in the scientific community remains fairly rudimentary as it was discovered fairly recently in 2004 [4]. However, the physiological implications that LSD-1 may have on medical conditions are being researched. LSD-1 has proposed roles in both diabetes and in cancer development.

1. Diabetes

Gluconeogenesis is a process in the body that results in the production of glucose from non-carbohydrate forms (such as lactic acid). G6Pase and FBP1 are critical enzymes in the gluconeogenesis pathway. LSD-1, although it can have both activating and inhibiting effects depending on external conditions, is proposed to have inhibiting effects on the transcription of both G6Pase and FBP1 [5]. Under healthy conditions, LSD-1 inhibits the transcription of these enzymes in order to regulate the blood glucose levels in the body. It was found that decreased amounts of LSD-1 in the body can induce hyperglycemia that contributes to the formation of both types of diabetes [5].

2. Cancer

Research has found that LSD-1 is over-expressed in many tumorous cancers. The proposed mechanism behind the carcinogenic role of LSD-1 focuses on the known tumor-suppressor gene, p53. The p53 protein acts as a transcription factor that activates the expression of many anti-proliferative proteins. LSD-1 has been found to remove a methyl group from the di-methylated Lys370 on p53 [6]. Similar to the proposed role of LSD-1 in diabetes, its demethylation of p53 is inhibitory and prevents its binding to DNA [6]. This inactivation of p53 is thought to prevent anti-proliferative operations in the cell and contribute to the development of multiple types of cancers.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 Stavropoulos P, Blobel G, Hoelz A. Crystal structure and mechanism of human lysine-specific demethylase-1. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006 Jul;13(7):626-32. Epub 2006 Jun 25. PMID:16799558 doi:10.1038/nsmb1113

- ↑ Yang M, Gocke CB, Luo X, Borek D, Tomchick DR, Machius M, Otwinowski Z, Yu H. Structural basis for CoREST-dependent demethylation of nucleosomes by the human LSD1 histone demethylase. Mol Cell. 2006 Aug 4;23(3):377-87. PMID:16885027 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.012

- ↑ Binda C, Angelini R, Federico R, Ascenzi P, Mattevi A. Structural bases for inhibitor binding and catalysis in polyamine oxidase. Biochemistry. 2001 Mar 6;40(9):2766-76. PMID:11258887

- ↑ Shi Y, Lan F, Matson C, Mulligan P, Whetstine JR, Cole PA, Casero RA, Shi Y. Histone demethylation mediated by the nuclear amine oxidase homolog LSD1. Cell. 2004 Dec 29;119(7):941-53. PMID:15620353 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.012

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Pan D, Mao C, Wang YX. Suppression of gluconeogenic gene expression by LSD1-mediated histone demethylation. PLoS One. 2013 Jun 5;8(6):e66294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066294. Print 2013. PMID:23755305 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066294

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 10.1042/BJ20121360.