Tutorial:The opioid receptor, a molecular switch

From Proteopedia

(→Natural Function) |

(→Natural Function) |

||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

The human body has different types of opioid receptors called mu, kappa and delta; the mu receptor in particular is responsible for the addictive nature of morphine and other similar opioids involved in the 2010s opioid crisis. A conceptual model of the opioid receptor integrated into the membrane is shown at the top of the page. It shows that the protein is made of a single chain that passes across the membrane multiple times (this structure is shared with a larger group of so-called [[7 pass transmembrane receptors]]) | The human body has different types of opioid receptors called mu, kappa and delta; the mu receptor in particular is responsible for the addictive nature of morphine and other similar opioids involved in the 2010s opioid crisis. A conceptual model of the opioid receptor integrated into the membrane is shown at the top of the page. It shows that the protein is made of a single chain that passes across the membrane multiple times (this structure is shared with a larger group of so-called [[7 pass transmembrane receptors]]) | ||

| + | [[Image:Endocytosis.jpg|thumb]] | ||

These opioid receptors interact with opioids via a process known as ligand binding[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ligand_(biochemistry)#Receptor/ligand_binding_affinity]. When an opioid molecule binds to its receptor, the shape of the receptor changes (a so-called conformational change[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conformational_change] occurs). This change in the receptor causes it to release a [[GTP-binding protein]] (otherwise known as a G protein), which signals the inside of the cell to behave differently, for example not to cause the sensation of pain. Also, by signalling to other neurons via dopamine binding to the [[dopamine receptor]], large doses of opioids can result in a feeling of pleasure. | These opioid receptors interact with opioids via a process known as ligand binding[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ligand_(biochemistry)#Receptor/ligand_binding_affinity]. When an opioid molecule binds to its receptor, the shape of the receptor changes (a so-called conformational change[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conformational_change] occurs). This change in the receptor causes it to release a [[GTP-binding protein]] (otherwise known as a G protein), which signals the inside of the cell to behave differently, for example not to cause the sensation of pain. Also, by signalling to other neurons via dopamine binding to the [[dopamine receptor]], large doses of opioids can result in a feeling of pleasure. | ||

| - | The part of the receptor that interacts with the G proteins can also bind to another protein in the cell called [[arrestin]]. Arrestin, as its name suggest, stops a given receptor from always being on. When arrestin is bound, the receptor and a bit of the membrane it is integrated in form a | + | The part of the receptor that interacts with the G proteins can also bind to another protein in the cell called [[arrestin]]. Arrestin, as its name suggest, stops a given receptor from always being on. When arrestin is bound, the receptor and a bit of the membrane it is integrated in form a tiny cell-like structure called a vesicle with the opioid binding site pointing inside (see figure at right). Due to increased acidity in the vesicle, the opioid receptor releases the bound opioid. Then, one of two events may occur; either the receptor is delivered back to the cell membrane, or it is broken down into its building blocks. |

To see the receptor in action, you can watch a 4:35 video that connects the activity of an individual with the switching of the receptor in the cell<span class="fas fa-video" style="color:#32CD32"></span> | To see the receptor in action, you can watch a 4:35 video that connects the activity of an individual with the switching of the receptor in the cell<span class="fas fa-video" style="color:#32CD32"></span> | ||

Revision as of 18:15, 18 December 2019

The opioid receptor, a protein on the surface of nerve cells, binds to opioids such as morphine, oxicodone, heroin, and fentanyl. Repeated intake of opioids changes the response to these molecules, and can lead to addiction.

Contents |

See also

This article explains, at a level appropriate to high school students or beginning college students, how the opioid receptor is switched on and off, and what happens inside the brain as a consequence. Other pages related to this topic are:

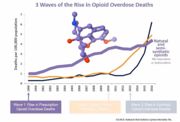

Relevance

When we want to turn on the lights in a dark room, we don't have to climb up a ladder to screw in a light bulb. All we have to do is flip a switch. A biological cell has switches, too, called receptors. Most are on the cell surface with a part sticking out, ready to bind to a signaling molecule. Another part of the receptor reaches into the inside of the cell, transmitting the signal. The opioid receptor can be switched on to relieve pain, for example during surgery. Tragically, it is very easy to become physically dependent on the signaling molecules. The ongoing opioid crisis in the USA shows how addictive opioids are (e.g. morphine, oxicodone, heroin, and fentanyl), with overdose deaths decreasing average life expectancy across the US population significantly.

Natural Function

Opioid receptors are proteins found in neurons, the cells that allow us to think, to observe our surroundings with our senses and to move our muscles. Like all cells, neurons have a water-insoluble structure called membrane (or lipid bilayer) surrounding them, keeping molecules from moving into and out of the cell. Opioid receptors are integrated into this membrane with parts reaching out of the cell and parts reaching into the cell, allowing it to act like a switch that is turned on from the outside and affecting the inside of the cell.

The human body has different types of opioid receptors called mu, kappa and delta; the mu receptor in particular is responsible for the addictive nature of morphine and other similar opioids involved in the 2010s opioid crisis. A conceptual model of the opioid receptor integrated into the membrane is shown at the top of the page. It shows that the protein is made of a single chain that passes across the membrane multiple times (this structure is shared with a larger group of so-called 7 pass transmembrane receptors)

These opioid receptors interact with opioids via a process known as ligand binding[1]. When an opioid molecule binds to its receptor, the shape of the receptor changes (a so-called conformational change[2] occurs). This change in the receptor causes it to release a GTP-binding protein (otherwise known as a G protein), which signals the inside of the cell to behave differently, for example not to cause the sensation of pain. Also, by signalling to other neurons via dopamine binding to the dopamine receptor, large doses of opioids can result in a feeling of pleasure.

The part of the receptor that interacts with the G proteins can also bind to another protein in the cell called arrestin. Arrestin, as its name suggest, stops a given receptor from always being on. When arrestin is bound, the receptor and a bit of the membrane it is integrated in form a tiny cell-like structure called a vesicle with the opioid binding site pointing inside (see figure at right). Due to increased acidity in the vesicle, the opioid receptor releases the bound opioid. Then, one of two events may occur; either the receptor is delivered back to the cell membrane, or it is broken down into its building blocks.

To see the receptor in action, you can watch a 4:35 video that connects the activity of an individual with the switching of the receptor in the cell [3]

Abuse, overdose and treatment

When it comes to opioid addiction, there are several steps involved with how it develops. The first step comes with the initial exposure. As exemplified in this fictional account , initial exposure can be through prescription medication. While some prescription medications include abuse-deterrent features, these have not prevent prescription drug abuse..

Once an individual takes an opioid medication, the aforementioned process transpires. When the arrestin begins to alter the cell's environment, it has with it a secondary effect. The process arrestin causes also develops drug tolerance[4], which makes the body more resistant to the pain-numbing and dopamine-releasing effects brought about by the presence of opioids in the body. Furthermore, the psychological impact of low pain and high dopamine result in the body desiring this effect from said opioids. Altogether, this sets the body up to take more and more opioids to get this feeling, and, in turn, building more and more tolerance. Attempting to go off of the drugs by this point results in withdrawal[5], which throws off the body's systems and the chemicals in the brain, altering personality and inflicting crippling side-effects.

When untreated, opioid overdose kills people because they stop breathing. The drug naloxone[6] can prevent overdose deaths when administered in time.

The continual presence of opioids in the body can have with it other effects. Within pregnant mothers, it may result in what is known as Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) , in which the fetus develops withdrawal symptoms after birth. This is due to the drugs passing through the placenta into the newborn's body prior to birth. Essentially, the infant becomes addicted before even being born, which, in turn, inflicts a myriad of health complications, some of which possibly fatal.

Structural highlights

| |||||||||||