We apologize for Proteopedia being slow to respond. For the past two years, a new implementation of Proteopedia has been being built. Soon, it will replace this 18-year old system. All existing content will be moved to the new system at a date that will be announced here.

User:Marcos Ngo/Sandbox 1

From Proteopedia

(Difference between revisions)

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

hNTHL1 has been observed in both the nucleus and mitochondria, meaning that the protein has dual transport signals to repair damaged bases. However, green fluorescent protein tagging experiments have shown localization exclusively to the nucleus, whereas studies using antibody tagging have reported presence in both compartments. Each tagging method has been criticized for potentially disrupting native protein folding, which could lead to incorrect localization. Importantly, nuclear localization signals (NLS) and mitochondrial localization signal (MLS) have been observed around the N-terminal region.<ref>https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/P78549/entry</ref> <ref>PMID:10882850</ref><ref>PMID:9705289</ref><ref>PMID:1478671</ref> | hNTHL1 has been observed in both the nucleus and mitochondria, meaning that the protein has dual transport signals to repair damaged bases. However, green fluorescent protein tagging experiments have shown localization exclusively to the nucleus, whereas studies using antibody tagging have reported presence in both compartments. Each tagging method has been criticized for potentially disrupting native protein folding, which could lead to incorrect localization. Importantly, nuclear localization signals (NLS) and mitochondrial localization signal (MLS) have been observed around the N-terminal region.<ref>https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/P78549/entry</ref> <ref>PMID:10882850</ref><ref>PMID:9705289</ref><ref>PMID:1478671</ref> | ||

| - | == | + | == Mechanism and Repair == |

DNA glycosylases follow a “pinch, push, plug, and pull” mechanism for lesion excision. First, the DNA is “pinched” by the enzyme, which destabilizes the helix. Next, they use a wedge amino acid to “push” the lesion out of the helix. While the lesion is being flipped out, another amino acid “plugs” into the helix to fill the gap and maintain the structure of the helix. Finally, the lesion is “pulled” into the active site to allow for lesion removal.<ref>https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2160&context=graddis</ref><ref>PMID:20469926</ref><ref>PMID:12220189</ref> | DNA glycosylases follow a “pinch, push, plug, and pull” mechanism for lesion excision. First, the DNA is “pinched” by the enzyme, which destabilizes the helix. Next, they use a wedge amino acid to “push” the lesion out of the helix. While the lesion is being flipped out, another amino acid “plugs” into the helix to fill the gap and maintain the structure of the helix. Finally, the lesion is “pulled” into the active site to allow for lesion removal.<ref>https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2160&context=graddis</ref><ref>PMID:20469926</ref><ref>PMID:12220189</ref> | ||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

== Structural Highlights == | == Structural Highlights == | ||

| - | This enzyme hNTHL1 belongs to the HhH (Helix-Hairpin-Helix) superfamily which consists of <scene name='10/1077482/Two_domains/2'>two alpha-helical domains</scene> | + | This enzyme hNTHL1 belongs to the HhH (Helix-Hairpin-Helix) superfamily which consists of <scene name='10/1077482/Two_domains/2'>two alpha-helical domains</scene> connected by two linkers. The solved structure of hNTHL1, with the first 63 residues being removed due to disorder, reveals <scene name='10/1077482/Ncfedomain1/5'>Domain 1</scene> with the iron sulfur cluster, N- and C-termini, and a catalytic residue (Asp). <scene name='10/1077482/Domain2features/3'>Domain 2</scene> has six helical barrels, hairpin-helix-hairpin, and the final catalytic residue (gly). The <scene name='10/1077482/Proglyhhh/1'>HhH</scene> motif has a characteristic glycine and proline-rich loop. The HhH allows for hydrogen bond interactions with the DNA backbone. <ref>PMID:12840008</ref><ref>https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2160&context=graddis</ref><ref>PMID:1283262</ref> |

This structure is captured in an <scene name='10/1077482/Open_conformation/1'>open conformation</scene> where the catalytic residues Lys220 and Asp239 are positioned approximately 25 Å apart, which is too far for catalysis. This implies that a conformational change is required to assemble the active site. To find the closed conformation, an engineered chimera was made by swapping the <scene name='10/1077482/Linker1/1'>flexible interdomain linker</scene> in human NTHL1 with a shorter, more rigid linker from a bacterial homolog. The <scene name='10/1077482/Chimera/1'>hNTHL1Δ63 chimera</scene> structure adopts a closed conformation where Lys220 and Asp239 are approximately 5 Å apart, which mimics the configuration seen in catalytically active homologs. The linker is not fully modeled due to disorder in the electron density map. <ref>PMID:34871433</ref> | This structure is captured in an <scene name='10/1077482/Open_conformation/1'>open conformation</scene> where the catalytic residues Lys220 and Asp239 are positioned approximately 25 Å apart, which is too far for catalysis. This implies that a conformational change is required to assemble the active site. To find the closed conformation, an engineered chimera was made by swapping the <scene name='10/1077482/Linker1/1'>flexible interdomain linker</scene> in human NTHL1 with a shorter, more rigid linker from a bacterial homolog. The <scene name='10/1077482/Chimera/1'>hNTHL1Δ63 chimera</scene> structure adopts a closed conformation where Lys220 and Asp239 are approximately 5 Å apart, which mimics the configuration seen in catalytically active homologs. The linker is not fully modeled due to disorder in the electron density map. <ref>PMID:34871433</ref> | ||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

The role of the <scene name='10/1077482/Fes_proper/4'>FeS Cluster</scene> is highly debated. One of the views is that the cluster is involved in scanning for lesions. Researchers found that oxidizing the FeS cluster in hNTHL1 from [4Fe-4S]^2+ to [4Fe-4S]^3+ increases its binding to DNA. When a mismatch such as C:A is introduced, this can disrupt DNA charge transport not allowing electrons to travel along the helix. This could stop the reduction of [4Fe-4S]^3+ to [4Fe-4S]^2+, leaving Nth bound until all lesions are removed. Another view is that the FeS cluster plays a role as a structural scaffold to stabilize the interaction of the protein with the DNA. A <scene name='10/1077482/Cys_and_fes/1'>Cys-Xaa6-Cys-Xaa2-Cys-Xaa5-Cys</scene> motif binds the iron sulfur cluster. <ref>PMID:19720997</ref><ref>PMID:28817778</ref><ref>DOI:https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2022/cc/d2cc03643f</ref><ref>PMID:8990169</ref> | The role of the <scene name='10/1077482/Fes_proper/4'>FeS Cluster</scene> is highly debated. One of the views is that the cluster is involved in scanning for lesions. Researchers found that oxidizing the FeS cluster in hNTHL1 from [4Fe-4S]^2+ to [4Fe-4S]^3+ increases its binding to DNA. When a mismatch such as C:A is introduced, this can disrupt DNA charge transport not allowing electrons to travel along the helix. This could stop the reduction of [4Fe-4S]^3+ to [4Fe-4S]^2+, leaving Nth bound until all lesions are removed. Another view is that the FeS cluster plays a role as a structural scaffold to stabilize the interaction of the protein with the DNA. A <scene name='10/1077482/Cys_and_fes/1'>Cys-Xaa6-Cys-Xaa2-Cys-Xaa5-Cys</scene> motif binds the iron sulfur cluster. <ref>PMID:19720997</ref><ref>PMID:28817778</ref><ref>DOI:https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2022/cc/d2cc03643f</ref><ref>PMID:8990169</ref> | ||

| - | The function of the <scene name='10/1077482/N-terminus_AlphaFold/3'>N-terminus</scene> (AlphaFold Prediction) of | + | The function of the <scene name='10/1077482/N-terminus_AlphaFold/3'>N-terminus</scene> (AlphaFold Prediction) of hNTHL1 has been a subject of study <ref>https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-03819-2/</ref><ref>PMID:37933859</ref>. It is theorized that the N-terminus, which is extended compared to homologs, functions as a means to remain bound to DNA, protecting the labile abasic site while waiting for its handoff with APE1. This was found through truncation of the N-terminal region (residues 1-96), which revealed that deletion of 55, 75, or 80 residues from the N-terminus resulted in a four to fivefold increase in catalytic activity. The rate-limiting step in hNTHL1's reaction is the release of the free 3’ aldehyde. <ref>PMID:12144783</ref> |

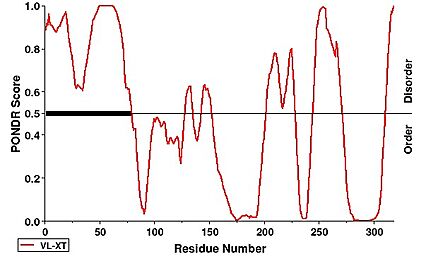

Notably, the first 63 residues were not modeled within the structure of hNHTL1, which is due to disorder. This can be observed under a PONDR prediction. | Notably, the first 63 residues were not modeled within the structure of hNHTL1, which is due to disorder. This can be observed under a PONDR prediction. | ||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

== Disease == | == Disease == | ||

| - | When the base excision repair pathway is compromised, this leads to limitations in enzymes to repair damaged DNA. This turns into mutations throughout the genome, leading to the progression of cancer. NTHL1-Tumor Syndrome is a disease caused by variants affecting the gene | + | When the base excision repair pathway is compromised, this leads to limitations in enzymes to repair damaged DNA. This turns into mutations throughout the genome, leading to the progression of cancer. NTHL1-Tumor Syndrome is a disease caused by variants affecting the gene that render the glycosylase inactive. This syndrome is diagnosed by a germline biallelic pathogenic variant through molecular genetic testing. When this is the case, one's cumulative lifetime risk of developing extracolonic cancer by age 60 is 45-78%. Oftentimes, this syndrome is characterized by an increased risk of colorectal cancer, breast cancer, and colorectal polyposis. Around 5% of colorectal cancers can be explained by germline mutations within a CRC predisposing gene. Exome sequencing has led to the identification of a homozygous nonsense mutation (c.268C>T encoding p.Q90*) in the base excision repair gene NTHL1 in three unrelated families.<ref>PMID:32239880</ref><ref>PMID:25938944</ref><ref>PMID:https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/NTH_HUMAN NTH_HUMAN</ref> |

A functional non-mutated version of hNTHL1 can additionally play a role in cancer cell survival. In triple-negative breast cancer, BCL11A, a protein, is frequently overexpressed. BCL11A is a transcription factor shown to stimulate hNTHL1 activity, enhancing base excision repair (BER) and enabling cancer cells to proliferate in high levels of oxidative DNA damage. Separately, Y-box binding protein-1 (YB-1) is overexpressed in tumor cells, and hNTHL1 can be activated through direct interaction with YB-1. This boosts its ability to process oxidized bases. This YB–1–mediated stimulation of hNTHL1 causes resistance to cisplatin, a form of chemotherapy, allowing for cancer proliferation. <ref>PMID:36186110</ref><ref>PMID:18307537</ref> | A functional non-mutated version of hNTHL1 can additionally play a role in cancer cell survival. In triple-negative breast cancer, BCL11A, a protein, is frequently overexpressed. BCL11A is a transcription factor shown to stimulate hNTHL1 activity, enhancing base excision repair (BER) and enabling cancer cells to proliferate in high levels of oxidative DNA damage. Separately, Y-box binding protein-1 (YB-1) is overexpressed in tumor cells, and hNTHL1 can be activated through direct interaction with YB-1. This boosts its ability to process oxidized bases. This YB–1–mediated stimulation of hNTHL1 causes resistance to cisplatin, a form of chemotherapy, allowing for cancer proliferation. <ref>PMID:36186110</ref><ref>PMID:18307537</ref> | ||

Revision as of 22:09, 27 April 2025

Human NTHL1

| |||||||||||