We apologize for Proteopedia being slow to respond. For the past two years, a new implementation of Proteopedia has been being built. Soon, it will replace this 18-year old system. All existing content will be moved to the new system at a date that will be announced here.

CRISPR-Cas Part II

From Proteopedia

(Difference between revisions)

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

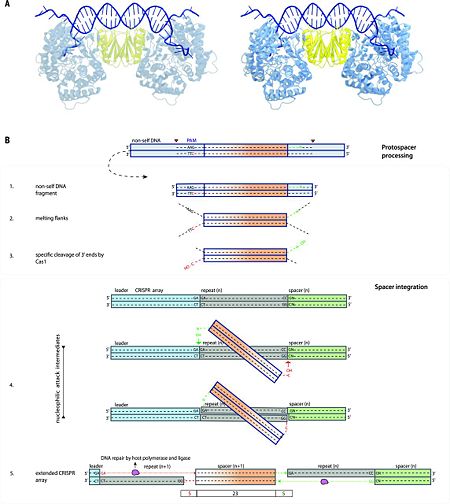

In the type II-A system, the Cas9-tracrRNA complex and Csn2 are involved in spacer acquisition along with the Cas1-Cas2 complex <ref name="Rev453">doi:10.1101/gad.257550.114</ref><ref name="Rev471">doi:10.1038/nature14245</ref>; the involvement of Cas9 in adaptation is likely to be a general feature of type II systems. Although the key residues of Cas9 involved in PAM recognition are dispensable for spacer acquisition, they are essential for the incorporation of new spacers with the correct PAM sequence <ref name="Rev471">doi:10.1038/nature14245</ref>. | In the type II-A system, the Cas9-tracrRNA complex and Csn2 are involved in spacer acquisition along with the Cas1-Cas2 complex <ref name="Rev453">doi:10.1101/gad.257550.114</ref><ref name="Rev471">doi:10.1038/nature14245</ref>; the involvement of Cas9 in adaptation is likely to be a general feature of type II systems. Although the key residues of Cas9 involved in PAM recognition are dispensable for spacer acquisition, they are essential for the incorporation of new spacers with the correct PAM sequence <ref name="Rev471">doi:10.1038/nature14245</ref>. | ||

| - | The involvement of Cas9 in PAM recognition and protospacer selection <ref name="Rev471">doi:10.1038/nature14245</ref> suggests that in type II systems Cas1 may have lost this role. Similarly, Cas4 that is present in subtypes IA-D and II-B has been proposed to be involved in the CRISPR adaptation process, and this prediction has been validated experimentally for type I-B <ref name="Rev465">doi:10.1093/nar/gkt1154</ref>. Cas4 is absent in the subtype II-C system of Campylobacter jejuni. Nonetheless, a conserved Cas4-like protein found in Campylobacter bacteriophages can activate spacer acquisition to use host DNA as an effective decoy to bacteriophage DNA. Bacteria that acquire self-spacers and escape phage infection must either overcome CRISPR-mediated autoimmunity by loss of the interference functions, leaving them susceptible to foreign DNA invasions, or tolerate changes in gene regulation (72). Furthermore, in subtypes I-U and V-B, Cas4 is fused to Cas1, which implies cooperation between these proteins during adaptation. In type I-F systems, Cas2 is fused to Cas3 (19), which suggests a dual role for Cas3 (20): involvement in adaptation as well as in interference. These findings support the coupling between the adaptation and interference stages of CRISPR-Cas defense during priming.<ref name="Rev4">doi:10.1126/science.aad5147</ref> | + | The involvement of Cas9 in PAM recognition and protospacer selection <ref name="Rev471">doi:10.1038/nature14245</ref> suggests that in type II systems Cas1 may have lost this role. Similarly, Cas4 that is present in subtypes IA-D and II-B has been proposed to be involved in the CRISPR adaptation process, and this prediction has been validated experimentally for type I-B <ref name="Rev465">doi:10.1093/nar/gkt1154</ref>. Cas4 is absent in the subtype II-C system of Campylobacter jejuni. Nonetheless, a conserved Cas4-like protein found in Campylobacter bacteriophages can activate spacer acquisition to use host DNA as an effective decoy to bacteriophage DNA. Bacteria that acquire self-spacers and escape phage infection must either overcome CRISPR-mediated autoimmunity by loss of the interference functions, leaving them susceptible to foreign DNA invasions, or tolerate changes in gene regulation <ref name="Rev472">doi:/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00744</ref>(72). Furthermore, in subtypes I-U and V-B, Cas4 is fused to Cas1, which implies cooperation between these proteins during adaptation. In type I-F systems, Cas2 is fused to Cas3 (19), which suggests a dual role for Cas3 (20): involvement in adaptation as well as in interference. These findings support the coupling between the adaptation and interference stages of CRISPR-Cas defense during priming.<ref name="Rev4">doi:10.1126/science.aad5147</ref> |

=Summary of the most extensively characterized CRISPR endoribonucleases<ref name="Rev3">PMID:25468820</ref><ref name="Rev4">doi:10.1126/science.aad5147</ref>= | =Summary of the most extensively characterized CRISPR endoribonucleases<ref name="Rev3">PMID:25468820</ref><ref name="Rev4">doi:10.1126/science.aad5147</ref>= | ||

Revision as of 11:12, 18 December 2016

| |||||||||||

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Mohanraju P, Makarova KS, Zetsche B, Zhang F, Koonin EV, van der Oost J. Diverse evolutionary roots and mechanistic variations of the CRISPR-Cas systems. Science. 2016 Aug 5;353(6299):aad5147. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5147. PMID:27493190 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.aad5147

- ↑ Stern A, Keren L, Wurtzel O, Amitai G, Sorek R. Self-targeting by CRISPR: gene regulation or autoimmunity? Trends Genet. 2010 Aug;26(8):335-40. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2010.05.008. Epub 2010, Jul 1. PMID:20598393 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2010.05.008

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Yosef I, Goren MG, Qimron U. Proteins and DNA elements essential for the CRISPR adaptation process in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012 Jul;40(12):5569-76. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks216. Epub 2012, Mar 8. PMID:22402487 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks216

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Wei Y, Terns RM, Terns MP. Cas9 function and host genome sampling in Type II-A CRISPR-Cas adaptation. Genes Dev. 2015 Feb 15;29(4):356-61. doi: 10.1101/gad.257550.114. PMID:25691466 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.257550.114

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Levy A, Goren MG, Yosef I, Auster O, Manor M, Amitai G, Edgar R, Qimron U, Sorek R. CRISPR adaptation biases explain preference for acquisition of foreign DNA. Nature. 2015 Apr 23;520(7548):505-10. doi: 10.1038/nature14302. Epub 2015 Apr 13. PMID:25874675 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature14302

- ↑ Erdmann S, Le Moine Bauer S, Garrett RA. Inter-viral conflicts that exploit host CRISPR immune systems of Sulfolobus. Mol Microbiol. 2014 Mar;91(5):900-17. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12503. Epub 2014 Jan 17. PMID:24433295 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/mmi.12503

- ↑ Wigley DB. RecBCD: the supercar of DNA repair. Cell. 2007 Nov 16;131(4):651-3. PMID:18022359 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.004

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Dupuis ME, Villion M, Magadan AH, Moineau S. CRISPR-Cas and restriction-modification systems are compatible and increase phage resistance. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2087. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3087. PMID:23820428 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3087

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Swarts DC, Mosterd C, van Passel MW, Brouns SJ. CRISPR interference directs strand specific spacer acquisition. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035888. Epub 2012 Apr 27. PMID:22558257 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035888

- ↑ Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Alkhnbashi OS, Costa F, Shah SA, Saunders SJ, Barrangou R, Brouns SJ, Charpentier E, Haft DH, Horvath P, Moineau S, Mojica FJ, Terns RM, Terns MP, White MF, Yakunin AF, Garrett RA, van der Oost J, Backofen R, Koonin EV. An updated evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015 Nov;13(11):722-36. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3569. Epub 2015, Sep 28. PMID:26411297 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro3569

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Nunez JK, Kranzusch PJ, Noeske J, Wright AV, Davies CW, Doudna JA. Cas1-Cas2 complex formation mediates spacer acquisition during CRISPR-Cas adaptive immunity. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014 May 4. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2820. PMID:24793649 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.2820

- ↑ Wang J, Li J, Zhao H, Sheng G, Wang M, Yin M, Wang Y. Structural and Mechanistic Basis of PAM-Dependent Spacer Acquisition in CRISPR-Cas Systems. Cell. 2015 Nov 5;163(4):840-53. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.008. Epub 2015 Oct, 17. PMID:26478180 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.008

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Nunez JK, Lee AS, Engelman A, Doudna JA. Integrase-mediated spacer acquisition during CRISPR-Cas adaptive immunity. Nature. 2015 Mar 12;519(7542):193-8. doi: 10.1038/nature14237. Epub 2015 Feb 18. PMID:25707795 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature14237

- ↑ van der Oost J, Jore MM, Westra ER, Lundgren M, Brouns SJ. CRISPR-based adaptive and heritable immunity in prokaryotes. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009 Aug;34(8):401-7. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.05.002. Epub, 2009 Jul 29. PMID:19646880 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2009.05.002

- ↑ Silas S, Mohr G, Sidote DJ, Markham LM, Sanchez-Amat A, Bhaya D, Lambowitz AM, Fire AZ. Direct CRISPR spacer acquisition from RNA by a natural reverse transcriptase-Cas1 fusion protein. Science. 2016 Feb 26;351(6276):aad4234. doi: 10.1126/science.aad4234. PMID:26917774 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.aad4234

- ↑ Fineran PC, Charpentier E. Memory of viral infections by CRISPR-Cas adaptive immune systems: acquisition of new information. Virology. 2012 Dec 20;434(2):202-9. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.10.003. Epub 2012, Nov 2. PMID:23123013 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2012.10.003

- ↑ Arslan Z, Hermanns V, Wurm R, Wagner R, Pul U. Detection and characterization of spacer integration intermediates in type I-E CRISPR-Cas system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014 Jul;42(12):7884-93. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku510. Epub 2014, Jun 11. PMID:24920831 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gku510

- ↑ Amitai G, Sorek R. CRISPR-Cas adaptation: insights into the mechanism of action. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016 Feb;14(2):67-76. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2015.14. Epub 2016 , Jan 11. PMID:26751509 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2015.14

- ↑ Datsenko KA, Pougach K, Tikhonov A, Wanner BL, Severinov K, Semenova E. Molecular memory of prior infections activates the CRISPR/Cas adaptive bacterial immunity system. Nat Commun. 2012 Jul 10;3:945. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1937. PMID:22781758 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1937

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Li M, Wang R, Zhao D, Xiang H. Adaptation of the Haloarcula hispanica CRISPR-Cas system to a purified virus strictly requires a priming process. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014 Feb;42(4):2483-92. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1154. Epub 2013, Nov 21. PMID:24265226 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkt1154

- ↑ Richter C, Dy RL, McKenzie RE, Watson BN, Taylor C, Chang JT, McNeil MB, Staals RH, Fineran PC. Priming in the Type I-F CRISPR-Cas system triggers strand-independent spacer acquisition, bi-directionally from the primed protospacer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014 Jul;42(13):8516-26. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku527. Epub 2014, Jul 2. PMID:24990370 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gku527

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Fineran PC, Gerritzen MJ, Suarez-Diez M, Kunne T, Boekhorst J, van Hijum SA, Staals RH, Brouns SJ. Degenerate target sites mediate rapid primed CRISPR adaptation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014 Apr 22;111(16):E1629-38. doi:, 10.1073/pnas.1400071111. Epub 2014 Apr 7. PMID:24711427 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1400071111

- ↑ Xue C, Seetharam AS, Musharova O, Severinov K, Brouns SJ, Severin AJ, Sashital DG. CRISPR interference and priming varies with individual spacer sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015 Dec 15;43(22):10831-47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1259. Epub, 2015 Nov 19. PMID:26586800 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv1259

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Vorontsova D, Datsenko KA, Medvedeva S, Bondy-Denomy J, Savitskaya EE, Pougach K, Logacheva M, Wiedenheft B, Davidson AR, Severinov K, Semenova E. Foreign DNA acquisition by the I-F CRISPR-Cas system requires all components of the interference machinery. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015 Dec 15;43(22):10848-60. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1261. Epub, 2015 Nov 19. PMID:26586803 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv1261

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Ivancic-Bace I, Cass SD, Wearne SJ, Bolt EL. Different genome stability proteins underpin primed and naive adaptation in E. coli CRISPR-Cas immunity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015 Dec 15;43(22):10821-30. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1213. Epub, 2015 Nov 17. PMID:26578567 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv1213

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Heler R, Samai P, Modell JW, Weiner C, Goldberg GW, Bikard D, Marraffini LA. Cas9 specifies functional viral targets during CRISPR-Cas adaptation. Nature. 2015 Mar 12;519(7542):199-202. doi: 10.1038/nature14245. Epub 2015 Feb, 18. PMID:25707807 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature14245

- ↑ doi: https://dx.doi.org//10.3389/fmicb.2014.00744

- ↑ Hochstrasser ML, Doudna JA. Cutting it close: CRISPR-associated endoribonuclease structure and function. Trends Biochem Sci. 2015 Jan;40(1):58-66. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.10.007. Epub, 2014 Nov 18. PMID:25468820 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2014.10.007

Categories: Topic Page | Crispr | Crispr-associated | Endonuclease | Cas9 | Cas6