User:Natalie Van Ochten/Sandbox 1

From Proteopedia

(Difference between revisions)

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

[[Image:The Normal DDAH Mechanism.jpg|400px|center|thumb|The normal DDAH mechanism]] | [[Image:The Normal DDAH Mechanism.jpg|400px|center|thumb|The normal DDAH mechanism]] | ||

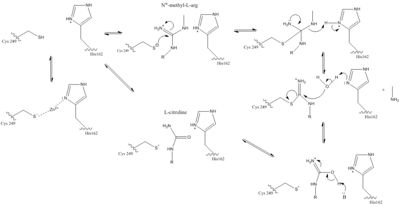

| - | There is a channel in the center of the protein that is closed by a <span class="plainlinks">[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salt_bridge_(protein_and_supramolecular) salt bridge]</span> connecting Glu77 and Lys174 <ref name="frey" />. This salt bridge constitutes the bottom of the active site. There is a pore containing water on one side of the channel. This pore is delineated by the first β strand of each of the five propeller blades. The water in the water-filled pore forms hydrogen bonds to His172 and Ser175. The other side of the channel is the active site. Short loop regions and a helical structure define the outward boundaries of this site. Active sites of DDAH from different organisms is similar. Amino acids involved in the chemical mechanism of creating products are also conserved. Amino acids in the lid region are not conserved except for a Leucine amino acid. When MMA or ADMA bind in the active site, they are broken down into L-citrulline and amines (Figure 1). L-citrulline leaves the active site when the lid opens. The amines can either leave through the entrance to the active site or through a pore made by movement of Glu77 and Lys174 <ref name="frey" />. | + | There is a channel in the center of the protein that is closed by a <span class="plainlinks">[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salt_bridge_(protein_and_supramolecular) salt bridge]</span> connecting Glu77 and Lys174 <ref name="frey" />. This salt bridge constitutes the bottom of the active site. There is a pore containing water on one side of the channel. This pore is delineated by the first β strand of each of the five propeller blades. The water in the water-filled pore forms hydrogen bonds to His172 and Ser175. The other side of the channel is the active site. Short loop regions and a helical structure define the outward boundaries of this site. Active sites of DDAH from different organisms is similar. Amino acids involved in the chemical mechanism of creating products are also <scene name='69/694225/Evolutionary_conservation/1'>conserved</scene>. Amino acids in the lid region are not conserved except for a Leucine amino acid. When MMA or ADMA bind in the active site, they are broken down into L-citrulline and amines (Figure 1). L-citrulline leaves the active site when the lid opens. The amines can either leave through the entrance to the active site or through a pore made by movement of Glu77 and Lys174 <ref name="frey" />. |

Revision as of 01:01, 31 March 2017

Dimethylarginine Dimethylaminohydrolase

| |||||||||||

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Palm F, Onozato ML, Luo Z, Wilcox CS. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH): expression, regulation, and function in the cardiovascular and renal systems. American Journal of Physiology. 2007 Dec 1;293(6):3227-3245. PMID:17933965 doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00998.2007

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Tran CTL, Leiper JM, Vallance P. The DDAH/ADMA/NOS pathway. Atherosclerosis Supplements. 2003 Dec;4(4):33-40. PMID:14664901 doi:10.1016/S1567-5688(03)00032-1

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 3.22 3.23 Frey D, Braun O, Briand C, Vasak M, Grutter MG. Structure of the mammalian NOS regulator dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase: a basis for the design of specific inhibitors. Structure. 2006 May;14(5):901-911. PMID:16698551 doi:10.1016/j.str.2006.03.006

- ↑ Janssen W, Pullamsetti SS, Cooke J, Weissmann N, Guenther A, Schermuly RT. The role of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH) in pulmonary fibrosis. The Journal of Pathology. 2012 Dec 12;229(2):242-249. Epub 2013 Jan. PMID:23097221 doi:10.1002/path.4127

- ↑ Humm A, Fritsche E, Mann K, Göhl M, Huber R. Recombinant expression and isolation of human L-arginine:glycine amidinotransferase and identification of its active-site cysteine residue. Biochemical Journal. 1997 March 15;322(3):771-776. PMID:9148748 doi:10.1042/bj3220771

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Rasheed M, Richter C, Chisty LT, Kirkpatrick J, Blackledge M, Webb MR, Driscoll PC. Ligand-dependent dynamics of the active site lid in bacterial Dimethyarginine Dimethylaminohydrolase. Biochemistry. 2014 Feb 18;53:1092-1104. PMCID:PMC3945819 doi:10.1021/bi4015924

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Stone EM, Costello AL, Tierney DL, Fast W. Substrate-assisted cysteine deprotonation in the mechanism of Dimethylargininase (DDAH) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochemistry. 2006 May 2;45(17):5618-5630. PMID:16634643 doi:10.1021/bi052595m

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Pace NJ, Weerpana E. Zinc-binding cysteines: diverse functions and structural motifs. Biomolecules. 2014 June;4(2):419-434. PMCID:4101490 doi:10.3390/biom4020419

- ↑ Colasanti M, Suzuki H. The dual personality of NO. ScienceDirect. 2000 Jul 1;21(7):249-252. PMID:10979862 doi:10.1016/S0165-6147(00)01499-1

- ↑ Rassaf T, Feelisch M, Kelm M. Circulating NO pool: assessment of nitrite and nitroso species in blood and tissues. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 2004 Feb 15;36(4):413-422. PMID:14975444 doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.11.011

- ↑ Tsao PS, Cooke JP. Endothelial alterations in hypercholesterolemia: more than simply vasodilator dysfunction. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 1998;32(3):48-53. PMID:9883748

- ↑ Vallance P, Leiper J. Blocking NO synthesis: how, where and why? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2002 Dec;1(12):939-950. PMID:12461516 doi:10.1038/nrd960