Introduction

Dimethylarginine Dimethyaminohydrolase EC 3.5.3.18 (commonly known as DDAH) is a member of the hydrolase family of enzymes which use water to break down molecules [1]. Specifically, DDAH is a nitric oxide synthase (NOS) regulator. Its metabolizes free arginine derivatives, namely NѠ,NѠ-dimethyl-L-arginine (ADMA) and NѠ-methyl-L-arginine (MMA) which competitively inhibit NOS [2]. DDAH converts MMA and ADMA to L-citrulline and monoamine or dimethylamine [3]. DDAH is expressed in the cytosol of cells in humans, mice, rates, sheep, cattle, and bacteria [1]. DDAH activity has been localized mainly to the brain, kidney, pancreas, and liver in these organisms. If DDAH is overexpressed, NOS can be activated [3]. ADMA and MMA can inhibit the synthesis of NO by competitively inhibiting all three kinds of NOS (endothelial, neuronal, and inducible) [3]. Underexpression or inhibition of DDAH decreases NOS activity and NO levels will decrease. Because of nitric oxide’s (NO) role in signaling and defense, NO levels in an organism must be regulated to reduce damage to cells [4]. NO is made by NOS creating L-citrulline from L-arginine [3]. In humans, many diseases can come from improper control of NO levels including diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Current research has identified several inhibitors of DDAH which could be important in fighting diseases involving irregular NO levels [3].

General Structure

DDAH’s has a propeller-like fold which is characteristic of the superfamily of L-arginine/glycine amidinotransferases [5]. This five-stranded propeller contains five repeats of a ββαβ motif [3]. This motif consists of two beta-sheets that are anti-parallel, an alpha helix, and another beta-sheet that is parallel to the second beta-sheet in the motif. These motifs in DDAH form a in the center of the protein structure. Lys174 and Glu77 form a in the channel that forms the bottom of the for the protein. One side of the channel is a , whereas the other side is the active site cleft that is defined by a short loop region and alpha helical structures [3].

Lid Region

Amino acids 25-36 of DDAH constitute the loop region of the protein [3]. This is more commonly known as the lid region. The lid is what allows the active site to be exposed to substrate binding or not. Studies have shown crystal structures of the lid at and conformations. In the open conformation, the lid forms an alpha helix and the amino acid Leu29 is moved so it does not interact with the active site. This allows the active site to be vulnerable to attack. This lid region is very flexible. This open conformation has been shown when DDAH had been crystallized when Zn(II) was bound at . There is a closed form which has been observed with Zn(II) binding at and in the unliganded enzyme. When the lid is closed, a specific hydrogen bond can form between the Leu29 carbonyl and the amino group on bound molecule. This stabilizes this complex. The Leu29 is then blocking the active site entrance [3]. Opening and closing the lid takes place faster than the actual reaction in the active site [6]. This suggests that the rate-limiting step of this reaction is not the lid movement but is the actual chemistry happening to the substrate in the active site of DDAH [6].

The specific residues in the lid region are different in different organisms [3]. The only consistent similarity is a conserved leucine residue in this lid that function to hydrogen bond with the ligand bound to the active site [6]. Different isoforms from the same species can have differences in lid regions as well [3]. DDAH-2 has a negatively charged lid while DDAH-1 has a positively charged lid [3].

Active Site

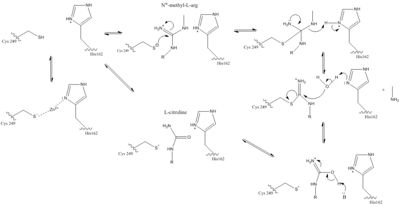

The normal DDAH regulation mechanism depends on the presence of in the active site that acts as a nucleophile in the mechanism [7]. The Cys249 is used to attack the guanidinium carbon on the substrate that is held in the active site via hydrogen bonds (Figure 1). This is followed by collapsing the tetrahedral product to get rid of the alkylamine leaving group. A thiouronium intermediate is then formed with sp2 hybridization. This intermediate is hydrolyzed to form citrulline. The His162 protonates the leaving group in this reaction and generates hydroxide to hydrolyze the intermediate formed in the reaction (Figure 1). Studies suggest that Cys249 is neutral until binding of guanidinium near Cys249 decreases Cys249’s pKa and deprotonates the thiolate to activate the nucleophile. Other studies suggest that the Cys249 and an active site His162 form an ion pair to deprotonate the thiolate. Cys249 and His162 can also form a binding site for inhibitors to bind to which stabilizes the thiolate. This is important in regulating NO activity in organisms and designing drugs to inhibit this enzyme [7].

There is a channel in the center of the protein that is closed by a connecting Glu77 and Lys174

[3]. This salt bridge constitutes the bottom of the active site. There is a pore containing water on one side of the channel. This pore is delineated by the first β strand of each of the five propeller blades. The water in the water-filled pore forms hydrogen bonds to His172 and Ser175. The other side of the channel is the active site. Short loop regions and a helical structure define the outward boundaries of this site. Active sites of DDAH from different organisms is similar. Amino acids involved in the chemical mechanism of creating products are also .

Color key for DDAH conservation

Amino acids in the lid region are not conserved except for a Leucine amino acid. When MMA or ADMA bind in the active site, they are broken down into L-citrulline and amines (Figure 1). L-citrulline leaves the active site when the lid opens. The amines can either leave through the entrance to the active site or through a pore made by movement of Glu77 and Lys174 [3].

Zn(II) Bound to the Active Site

In DDAH, Zinc (ZnII) acts as an endogenous inhibitor and prevents normal NOS activity [3]. The Zn(II)-binding site is located inside the protein’s active site, which makes it a competitive inhibitor. When bound, Zn(II) blocks the entrance of any other substrate. It was found that Cys273, His172, Glu77, Asp78, and Asp 268 all play a role in the binding of Zn(II). directly coordinates with the Zn(II) ion in the active site while the other significant residues stabilize the ion via hydrogen bonding interactions with water molecules in the active site. Depending on pH, His172 can and use the imidazole group to directly coordinate the Zn(II) ion. Cys273, which is conserved between bovine and humans, is the key active site residue that coordinates Zn(II) [3]. Zinc-cysteine complexes have been found to be important mediators of protein catalysis, regulation, and structure [8]. Cys273 and the water molecules stabilize the Zn(II) ion in a tetrahedral environment. The Zn(II) dissociation constant is 4.2 nM which is consistent with the nanomolar concentrations of Zn(II) in the cells, which provides more evidence for the regulatory use of Zn(II) by DDAH [8].

Zn(II) bound at differing pH vlaues

Inhibitors

and bind in the active site in the same orientation to create the same intermolecular bonds between them and DDAH [3]. L-citrulline is a product of DDAH hydrolyzing ADMA and MMA, suggesting DDAH activity creates a negative feedback loop on itself. Both molecules enter the active site and cause DDAH to be in its closed lid formation. The α carbon on either molecule creates three salt bridges with DDAH: two with the guanidine group of Arg144 and one with the guanidine group Arg97. Another salt bridge is formed between the ligand and Asp72. The molecules are stabilized in the active site by hydrogen bonds: α carbon-amino group of the ligand to main chain carbonyls of Val267 and Leu29. Hydrogen bonds also form between the side chains of Asp78 and Glu77 with the ureido group of L-citrulline.

Like L-homocysteine and L-citrulline, binds and the lid region of DDAH is closed. When DDAH reacts with S-nitroso-L-homocysteine, a covalent product, N-thiosulfximide exist in the active site because of its binding to Cys273. N-thiosulfximide is stabilized by several salt bridges and hydrogen bonds. Arg144 and Arg97 stabilize the α carbon-carbonyl group via salt bridges, and Leu29, Val267, and Asp72 stabilize the α carbon-amino group by forming hydrogen bonds [3].

Different Isoforms

DDAH has two main isoforms [3]. DDAH-1 colocalizes with nNOS (neuronal NOS). This enzyme is found mainly in the brain and kidney of organisms [2]. DDAH-2 is found in tissues with eNOS (endothelial NOS) [3]. DDAH-2 localization has been found in the heart, kidney, and placenta [2]. Additionally, studies show that DDAH-2 is expressed in iNOS containing immune tissues (inducible NOS) [3]. Both of the isoforms have conserved residues that are involved in the catalytic mechanism of DDAH (Cys, Asp, and His). The differences between the isoforms is in the substrate binding residues and the lid region residues. DDAH-1 has a positively charged lid region while DDAH-2 has negatively charged lid. In total, three salt bridge differ between DDAH-1 and DDAH-2 isoforms. Researchers can take advantage of the fact that there are two different isoforms of this enzyme and create drugs that target one isoform over another to control NO levels in specific tissues in the body [3].

Medical Relevancy

DDAH works to hydrolyze MMA and ADMA [3]. Both MMA and ADMA competitively inhibit NO synthesis by inhibiting Nitric Oxide Synthase (NOS). NO is an important signaling and effector molecule in neurotransmission, bacterial defense, and regulation of vascular tone [9]. Because NO is highly toxic, freely diffusible across membranes, and its radical form is fairly reactive, cells must maintain a large control on concentrations by regulating NOS activity and the activity of enzymes such as DDAH that have an indirect effect of the concentration of NO [10]. An imbalance of NO contributes to several diseases. Low NO levels, potentially caused by low DDAH activity and therefore high MMA and ADMA concentrations, have been implicated with diseases such as uremia, chronic heart failure, atherosclerosis, and hyperhomocysteinemia [11]. High levels of NO have been involved with diseases such as septic shock, migraine, inflammation, and neurodegenerative disorders [12]. Because of the effects on NO levels and known inhibitors to DDAH, regulation of DDAH may be an effective way to regulate NO levels therefore treating these diseases [3].