User:David Ryskamp/Sandbox1

From Proteopedia

(Difference between revisions)

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

Polyadenylation of an mRNA involves the recognition of the 5’-AAUAAA-3’ consensus site, the cleavage downstream of the consensus site, and then the addition of adenines by [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polynucleotide_adenylyltransferase Poly(A) Polymerase] to the 3’ end. The newly added poly(A) tail is associated with the PABP. PABP requires 11-12 adenosines in order to bind. PABP and the bound Poly(A) tail work together to stabilize mRNA by preventing exo-ribonucleolytic degradation,<ref name="Recognition of Polyadenylate RNA by the Poly(A)-Binding Protein">Deo, Rahul C, et al. “Recognition of Polyadenylate RNA by the Poly(A)-Binding Protein.” Cell 98:6. (1999) 835-845. Print. </ref> thereby guiding the mRNA molecule into the translation pathway. Upon mRNA poly(A) recognition, PABP and the bound mRNA stimulate the initiation of translation by interacting with initiation factor [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/EIF4G eIF4G]. | Polyadenylation of an mRNA involves the recognition of the 5’-AAUAAA-3’ consensus site, the cleavage downstream of the consensus site, and then the addition of adenines by [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polynucleotide_adenylyltransferase Poly(A) Polymerase] to the 3’ end. The newly added poly(A) tail is associated with the PABP. PABP requires 11-12 adenosines in order to bind. PABP and the bound Poly(A) tail work together to stabilize mRNA by preventing exo-ribonucleolytic degradation,<ref name="Recognition of Polyadenylate RNA by the Poly(A)-Binding Protein">Deo, Rahul C, et al. “Recognition of Polyadenylate RNA by the Poly(A)-Binding Protein.” Cell 98:6. (1999) 835-845. Print. </ref> thereby guiding the mRNA molecule into the translation pathway. Upon mRNA poly(A) recognition, PABP and the bound mRNA stimulate the initiation of translation by interacting with initiation factor [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/EIF4G eIF4G]. | ||

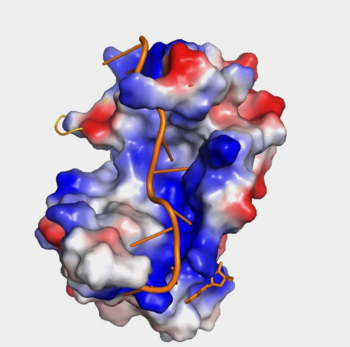

| + | [[Image:Hydrophobicity (1).png|350px|left|thumb| "Figure 1:" Surface hydrophobicity shown in presence of mRNA]] | ||

===mRNA Stabilization=== | ===mRNA Stabilization=== | ||

| Line 52: | Line 53: | ||

===Eukaryotic Translation Initiation=== | ===Eukaryotic Translation Initiation=== | ||

| - | Upon mRNA Poly(A) recognition, PABP and the bound mRNA stimulate the initiation of translation by interacting with initiation factor eIF4G. Protein eIF4G actually interacts with PABP's dorsal side (under the trough) hydrophobic and acidic residues that stimulate the interaction between the two proteins | + | Upon mRNA Poly(A) recognition, PABP and the bound mRNA stimulate the initiation of translation by interacting with initiation factor eIF4G. Protein eIF4G actually interacts with PABP's dorsal side (under the trough) hydrophobic and acidic residues that stimulate the interaction between the two proteins. These specific residues are phylogenetically conserved among all PABPs, and therefore significant in the protein's function and interaction with eIF4G. |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

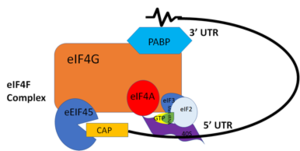

PABP and mRNA complex aids in translation initiation under two proposed mechanisms. Within the two mechanisms, studies have highlighted the presence The “Closed Loop” Model entails the recognition of the 5’ 7-methyl-Guanosine cap by [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eukaryotic_initiation_factor_4F eIF4F], which is a ternary complex made up of a cap-binding protein [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/EIF4E (eIF4E)] and RNA helicase [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/EIF4A (eIF4A)] connected by the bridging protein (eIF4G) (Figure 2).¹ Translation initiation is stimulated by the PABP bound to the poly(A) tail and its association with eIF4G.<ref name="Recognition of Polyadenylate RNA by the Poly(A)-Binding Protein">Deo, Rahul C, et al. “Recognition of Polyadenylate RNA by the Poly(A)-Binding Protein.” Cell 98:6. (1999) 835-845. Print. </ref> The 5’ UTR is unwound by the elF4F complex, and ribosomes are recruited to create the initiation complex. The eIF4G protein then guides the 40S subunit to the start codon (AUG), which is followed by the binding 60S ribosomal subunit, creating the 80S initiation complex.<ref name="Recognition of Polyadenylate RNA by the Poly(A)-Binding Protein">Deo, Rahul C, et al. “Recognition of Polyadenylate RNA by the Poly(A)-Binding Protein.” Cell 98:6. (1999) 835-845. Print. </ref> The association of the PABP and eIF4G gave rise to the name “closed loop.”<ref name="Recognition of Polyadenylate RNA by the Poly(A)-Binding Protein">Deo, Rahul C, et al. “Recognition of Polyadenylate RNA by the Poly(A)-Binding Protein.” Cell 98:6. (1999) 835-845. Print. </ref> Mutations of Arg→Ala and Lys→Ala in human eIF4G and in yeast extracts decrease the rate of translation initiation and destabilizing the interactions with PABP, indicating that basic residues are essential to the interaction with PABP.<ref name="Recognition of Polyadenylate RNA by the Poly(A)-Binding Protein">Deo, Rahul C, et al. “Recognition of Polyadenylate RNA by the Poly(A)-Binding Protein.” Cell 98:6. (1999) 835-845. Print. </ref> | PABP and mRNA complex aids in translation initiation under two proposed mechanisms. Within the two mechanisms, studies have highlighted the presence The “Closed Loop” Model entails the recognition of the 5’ 7-methyl-Guanosine cap by [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eukaryotic_initiation_factor_4F eIF4F], which is a ternary complex made up of a cap-binding protein [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/EIF4E (eIF4E)] and RNA helicase [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/EIF4A (eIF4A)] connected by the bridging protein (eIF4G) (Figure 2).¹ Translation initiation is stimulated by the PABP bound to the poly(A) tail and its association with eIF4G.<ref name="Recognition of Polyadenylate RNA by the Poly(A)-Binding Protein">Deo, Rahul C, et al. “Recognition of Polyadenylate RNA by the Poly(A)-Binding Protein.” Cell 98:6. (1999) 835-845. Print. </ref> The 5’ UTR is unwound by the elF4F complex, and ribosomes are recruited to create the initiation complex. The eIF4G protein then guides the 40S subunit to the start codon (AUG), which is followed by the binding 60S ribosomal subunit, creating the 80S initiation complex.<ref name="Recognition of Polyadenylate RNA by the Poly(A)-Binding Protein">Deo, Rahul C, et al. “Recognition of Polyadenylate RNA by the Poly(A)-Binding Protein.” Cell 98:6. (1999) 835-845. Print. </ref> The association of the PABP and eIF4G gave rise to the name “closed loop.”<ref name="Recognition of Polyadenylate RNA by the Poly(A)-Binding Protein">Deo, Rahul C, et al. “Recognition of Polyadenylate RNA by the Poly(A)-Binding Protein.” Cell 98:6. (1999) 835-845. Print. </ref> Mutations of Arg→Ala and Lys→Ala in human eIF4G and in yeast extracts decrease the rate of translation initiation and destabilizing the interactions with PABP, indicating that basic residues are essential to the interaction with PABP.<ref name="Recognition of Polyadenylate RNA by the Poly(A)-Binding Protein">Deo, Rahul C, et al. “Recognition of Polyadenylate RNA by the Poly(A)-Binding Protein.” Cell 98:6. (1999) 835-845. Print. </ref> | ||

Revision as of 17:15, 6 April 2018

Human Poly(A) Binding Protein (1CVJ)

| |||||||||||

References

- ↑ Blobel, Gunter. “A Protein of Molecular Weight 78,000 Bound to the Polyadenylate Region of Eukaryotic Messenger Rnas.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 70, no. 3, 1973, pp. 924–8.

- ↑ Baer, Bradford W. and Kornberg, Roger D. "The Protein Responsible for the Repeating Structure of Cytoplasmic Poly(A)-Ribonucleoprotein." The Journal of Cell Biology, vol. 96, no. 3, Mar. 1983, pp. 717-721. EBSCOhost.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 Deo, Rahul C, et al. “Recognition of Polyadenylate RNA by the Poly(A)-Binding Protein.” Cell 98:6. (1999) 835-845. Print.

- ↑ Kühn, Uwe and Elmar, Wahle. “Structure and Function of Poly(a) Binding Proteins.” Bba - Gene Structure & Expression, vol. 1678, no. 2/3, 2004.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Gorgoni, Barbra, and Gray, Nicola. “The Roles of Cytoplasmic Poly(A)-Binding Proteins in Regulating Gene Expression: A Developmental Perspective.” Briefings in Functional Genomics and Proteomics, vol. 3, no. 2, 1 Aug. 2004, pp. 125–141., doi:10.1093/bfgp/3.2.125.

- ↑ Wang, Zuoren and Kiledjian, Megerditch. “The Poly(A)-Binding Protein and an mRNA Stability Protein Jointly Regulate an Endoribonuclease Activity.” Molecular and Cellular Biology 20.17 (2000): 6334–6341. Print.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 “Oculopharyngeal Muscular Dystrophy.” NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders), rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/oculopharyngeal-muscular-dystrophy/.

- ↑ Richard, Pascale, et al. “Correlation between PABPN1 Genotype and Disease Severity in Oculopharyngeal Muscular Dystrophy.” Neurology, vol. 88, no. 4, 2016, pp. 359–365., doi:10.1212/wnl.0000000000003554.