Main Page

From Proteopedia

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

<th style="padding: 10px;background-color: #dae4d9">Art on Science</th> | <th style="padding: 10px;background-color: #dae4d9">Art on Science</th> | ||

<th style="padding: 10px;background-color: #f1b840">Journals</th> | <th style="padding: 10px;background-color: #f1b840">Journals</th> | ||

| - | <th style="padding: 10px;background-color: # | + | <th style="padding: 10px;background-color: #79baff">Education</th> |

</tr> | </tr> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

Revision as of 12:39, 18 October 2018

|

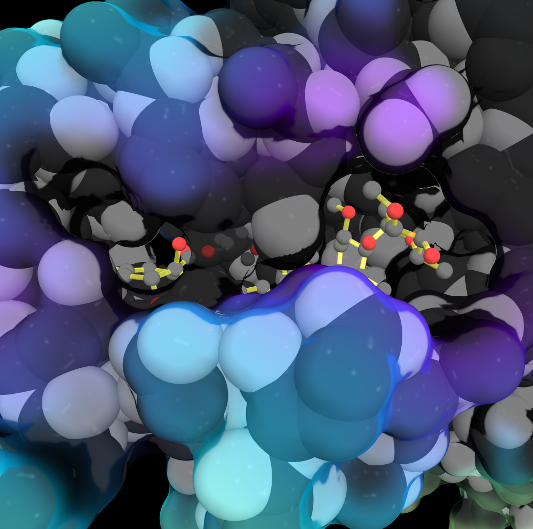

Because life has more than 2D, Proteopedia helps to understand relationships between structure and function. Proteopedia is a free, collaborative 3D-encyclopedia of proteins & other molecules. ISSN 2310-6301 | |||||||||||

| Selected Pages | Art on Science | Journals | Education | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||