Introduction

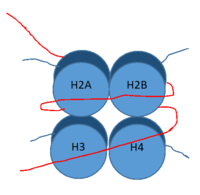

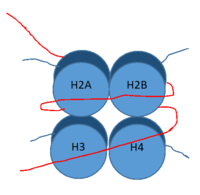

DNA (red) wrapped around histone proteins with histone tails (blue)

LSD-1 is a lysine demethylase. A histone is a blah blah blah and can be seen in Fig. 1.

Structure

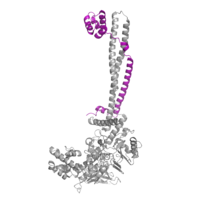

Figure 1:LSD1 overall 3D structure: Tower domain (blue), SWIRM domain (yellow), and Oxidase domain (red).

Tower Domain

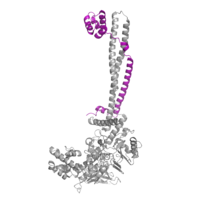

Figure 2: CoRest complex (purple) bound to LSD1 at the Tower domain.

The is a protrusion off the main protein body of LSD-1 comprised of 100 residues, which form 2 𝛂-helices. The longer helix, T𝛂A, is an LSD-1 specific element that has not been found in any other oxidase proteins [1]. The shorter helix, T𝛂B, is very near to the active site of the oxidase domain. In fact, T𝛂B connects directly to helix 𝛂D of the oxidase domain through a highly conserved connector loop. The exact function of the tower domain is not known, but it is proposed to regulate the size of the active site chamber through this . The T𝛂B-𝛂D interaction is responsible for the proper positioning of , a side chain of 𝛂D that is located in the catalytic chamber. In addition, the T𝛂B-𝛂D interaction positions 𝛂D in the correct manner to provide hydrogen bonding to . Tyr761 is positioned in the catalytic chamber very close to the FAD cofactor, and aids in the binding of the lysine substrate [1]. Therefore, the base of the tower domain forms a direct connection to the oxidase domain and plays a crucial role in the shape and catalytic activity of the active site. In fact, removing the tower domain via a mutation resulted in a drastic decrease in catalytic efficiency [1]. The tower domain has also been found to interact with other proteins and complexes, such as CoREST (Figure 2), as a molecular lever to allosterically regulate the catalytic activity of the active site [2]. Overall, the exact function of the tower domain has not yet been determined, but it is known to be vital to the catalytic activity of LSD-1.

SWIRM Domain

Oxidase Domain

The oxidase domain is responsible for housing the site of catalytic activity in LSD-1. The domain has two distinct subunits: one non-covalently binds the FAD cofactor and the other acts in both the binding and recognition of the substrate lysine on a histone tail [1]. The active site cavity is placed within the substrate-binding subunit of the oxidase domain and is unique due to its great size. In relation to other FAD-dependent oxidases, LSD-1 has an immense active site cavity that is 15 Å deep and 25 Å at its widest opening [1]. In comparison, polyamine oxidase, another FAD-dependent oxidase, has a catalytic chamber roughly 30 Å long but only a few angstroms wide [3]. The relatively large size of the LSD-1 active site cavity suggests that additional residues, in addition to the substrate lysine, enter into the active site during catalysis. These additional residues could participate in substrate recognition and may contribute to the enzyme’s specificity for H3K4 and H3K9.

Active Site and FAD Cofactor

Mechanism of Active Site

Figure X: Hydride transfer mechanism of LSD-1 active site via FAD cofactor.

This is a picture of the .

These are the different

The is ALSO a blah blah blah.

Inhibition by Tri-Methylated Lysine

Medical Implications

1. Cancer

2. Diabetes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Stavropoulos P, Blobel G, Hoelz A. Crystal structure and mechanism of human lysine-specific demethylase-1. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006 Jul;13(7):626-32. Epub 2006 Jun 25. PMID:16799558 doi:10.1038/nsmb1113

- ↑ Yang M, Gocke CB, Luo X, Borek D, Tomchick DR, Machius M, Otwinowski Z, Yu H. Structural basis for CoREST-dependent demethylation of nucleosomes by the human LSD1 histone demethylase. Mol Cell. 2006 Aug 4;23(3):377-87. PMID:16885027 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.012

- ↑ Binda C, Angelini R, Federico R, Ascenzi P, Mattevi A. Structural bases for inhibitor binding and catalysis in polyamine oxidase. Biochemistry. 2001 Mar 6;40(9):2766-76. PMID:11258887