We apologize for Proteopedia being slow to respond. For the past two years, a new implementation of Proteopedia has been being built. Soon, it will replace this 18-year old system. All existing content will be moved to the new system at a date that will be announced here.

Hemeproteins

From Proteopedia

(Difference between revisions)

| Line 126: | Line 126: | ||

*<scene name='77/774654/Cv/8'>Fe coordination site</scene>. | *<scene name='77/774654/Cv/8'>Fe coordination site</scene>. | ||

*<scene name='77/774654/Cv/9'>Distances between Lauric acid oxygens and heme group Fe</scene> in Cytochrome P450 hydroxylase from ''Steptomyces avermitilis'' (PDB code [[5cwe]]). | *<scene name='77/774654/Cv/9'>Distances between Lauric acid oxygens and heme group Fe</scene> in Cytochrome P450 hydroxylase from ''Steptomyces avermitilis'' (PDB code [[5cwe]]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Cytochrome c Nitrite Reductase= | ||

| + | |||

| + | Cytochrome c nitrite reductase (ccNIR) is a central enzyme of the nitrogen cycle. It binds nitrite, and reduces it by transferring 6 electrons to form ammonia. This ammonia can then be utilized to synthesize nitrogen containing molecules such as amino acids or nucleic acids. However, ccNiR’s primary role is to help extract energy from the reduction; ammonia is simply a potentially useful byproduct. In general, heterotrophic organisms feed on electron-rich substances such as sugars or fatty acids. During the metabolism of these substances large numbers of electrons are produced. Many organisms use oxygen as the final acceptor of these electrons, in which case water is formed. However, some organisms can use alternative electron acceptors such as nitrite, which is where ccNiR comes in. | ||

| + | The ccNiR described here is produced by the ''Shewanella oneidensis'' bacterium, which is remarkable in its own right due to the large number of electron acceptors that it can utilize. ''Shewanella'' is a facultative anaerobe, which means that it will use oxygen if available, but in the absence of oxygen can get rid of its electrons by dumping them on a wide range of alternate acceptors, of which nitrite is only one example. To handle the electron flow ''Shewanella'' uses a large number of promiscuous <scene name='Journal:JBIC:16/Cv/8'>c-heme</scene> containing electron transfer proteins. Indeed, ''Shewanella'' is exceptionally adept at producing c-heme proteins under fast-growth conditions, which many bacteria commonly used for large-scale laboratory gene expression, such as ''E. coli'', are incapable of unless they are first extensively reprogrammed genetically. Since ''Shewanella'' can be easily grown in the lab, and can naturally and easily produce c-hemes, it is an ideal host for generating large quantities of c-heme proteins such as ccNiR. | ||

| + | The 2012 paper by Youngblut et al. <ref name="Youngblut">none yet</ref> describes a genetically modified ''Shewanella'' strain that can produce 20 – 40 times more ccNiR per liter of culture than the wild type bacterium. The ccNir so produced can be purified easily and in large amounts. This result is important because c-heme proteins have historically proved difficult to over-express in traditional vectors such as ''E. coli''. With large quantities of ''Shewanella'' ccNIR available, Youngblut et al <ref name="Youngblut">none yet</ref> were able to obtain the crystal structure ([[3ubr]]) and do a variety of experiments. The ccNIR consists of <scene name='Journal:JBIC:16/Cv/4'>two equal subunits</scene> (<font color='darkmagenta'><b>colored in darkmagenta</b></font> and <span style="color:lime;background-color:black;font-weight:bold;">in green</span>) with <scene name='Journal:JBIC:16/Cv/5'>five c-hemes each</scene>. In the oxidized ccNIR all central heme irons are Fe3+. They can be subsequently reduced to Fe2+ either by reducing agents or electrochemically. An important conclusion of the paper is that electrons added to ccNiR are likely <scene name='Journal:JBIC:16/Cv/6'>delocalized over several hemes</scene>, rather than localized on individual hemes. | ||

| + | The <span style="color:yellow;background-color:black;font-weight:bold;">hemes 3-5 (colored in yellow)</span> and the <span style="color:seagreen;background-color:black;font-weight:bold;">hemes-2 (colored in seagreen)</span> are six coordinate and used for electron transport only, whereas the <font color='magenta'><b>two hemes-1 (colored in magenta)</b></font> are the active sites. Electrons are believed to enter via the <span style="color:seagreen;background-color:black;font-weight:bold;">hemes-2</span>, but can move between subunits. Though the physiological significance of this result is not yet known, it is possible that delocalizing the electrons keeps the active site redox-potential sufficiently high until enough electrons are accumulated that the reaction with nitrite can take place. That is, CcNIR acts like a capacitor that can store electrons until they are needed. The X-ray structure of the ccNIR reveals the architecture of this capacitor. To solve the structure a non-standard method, the Laue method, was used. This became necessary since attempts to collect a high resolution data set with monochromatic X-ray radiation were not successful. At room temperature the ccNIR crystals are susceptible to radiation damage. Freezing damaged the crystals because a suitable cryoprotectant could not be found. Single pulsed Laue crystallography with 100 ps highly intense polychromatic X-ray pulses provided a solution. A dataset was collected in a few minutes. The crystals were cooled slightly to 0 °C but not frozen. Crystal settings spanned a range of 180 °C and the crystals were orthorhombic. Therefore, a Laue dataset with very high multiplicity and good quality in terms of resolution and R<sub>merge</sub> could be collected. The structure of this ccNIR was then solved by molecular replacement using the ''E. coli'' ccNIR as a template. <scene name='Journal:JBIC:16/Cv/10'>An overlay</scene> of the ''S. oneidensis'' hemes within one monomer with the corresponding ''E. coli'' hemes reveals significant similarity. ''S. oneidensis'' <span style="color:yellow;background-color:black;font-weight:bold;">hemes 3-5</span>, <span style="color:seagreen;background-color:black;font-weight:bold;">hemes-2</span>, and <font color='magenta'><b>hemes-1</b></font> are colored in <span style="color:yellow;background-color:black;font-weight:bold;">yellow</span>, <span style="color:seagreen;background-color:black;font-weight:bold;">seagreen</span>, and <font color='magenta'><b>magenta</b></font>, respectively, whereas their corresponding ''E. coli'' hemes are in similar, but darker colors. The <scene name='Journal:JBIC:16/Cv/11'>overall structure</scene> of ''S. oneidensis'' ccNiR also is similar to that of ''E. coli'' ccNiR, except in the region where the enzyme interacts with its physiological electron donor (CymA in the case of ''S. oneidensis'' ccNiR, NrfB in the case of the ''E. coli'' protein) near heme 2. Subunits of ''S. oneidensis'' ccNiR <font color='darkmagenta'><b>colored in darkmagenta</b></font> and <span style="color:lime;background-color:black;font-weight:bold;">in green</span>; subunits of ''E. coli'' ccNiR <span style="color:hotpink;background-color:black;font-weight:bold;">colored in hot pink</span> and <span style="color:deepskyblue;background-color:black;font-weight:bold;">in deep-sky-blue</span>. | ||

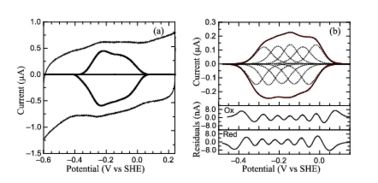

| + | Protein film voltammetry (PFV) experiments performed on ''S. oneidensis'' ccNiR films in the absence of substrate produced a broad envelope of reversible signals that span approximately 450 mV. At high pH values the envelope appears as a single peak, whereas at pH values below 7 the envelope appears to be composed of two large overlapping peaks. At pH values below 6 and at 0 °C, the envelope of signal can be better resolved and more than two peaks can be observed. This resulting envelope of signal can be deconvoluted as the sum of five one-electron peaks, each corresponding to one of the five hemes in a ccNiR monomer (see image below). | ||

| + | [[Image:figur5.jpg|left|378px|thumb|PFV of ''S. oneidensis'' ccNiR (a) Typical signal on a graphite electrode. (b) Baselinesubtracted non-turnover voltammogram]] | ||

| + | The Ca<sup>2+</sup> ion within <scene name='Journal:JBIC:16/Cv/14'>conserved site</scene> is coordinated in bidentate fashion by <scene name='Journal:JBIC:16/Cv/15'>Glu205</scene>, and in monodentate fashion by the <scene name='Journal:JBIC:16/Cv/16'>Tyr206 and Lys254</scene> backbone carbonyls, and the <scene name='Journal:JBIC:16/Cv/17'>Gln256</scene> side-chain carbonyl. In the ''S. oneidensis'' structure only <scene name='Journal:JBIC:16/Cv/18'>one water molecule</scene> is assigned to the Ca<sup>2+</sup> ion in subunit B. In subunit A the difference electron density that represents this water molecule is very close to the noise level, and it is difficult to identify even one water molecule there. The <scene name='Journal:JBIC:16/Cv/14'>carbonyl side chain of Asp242 and the hydroxyl of Tyr235</scene> come near to the open calcium coordination sites, but are not within bonding distance. Instead they interact with the water molecule that is weakly coordinated to the Ca<sup>2+</sup> ion. The ccNiR calcium ions appear to play a vital role in organizing the <scene name='Journal:JBIC:16/Cv/13'>active site</scene> (as was mentioned above <font color='magenta'><b>hemes-1</b></font> are the active sites). | ||

=[[Hemoglobin]]= | =[[Hemoglobin]]= | ||

=[[Myoglobin]]= | =[[Myoglobin]]= | ||

Revision as of 15:18, 11 November 2019

| |||||||||||

References

- ↑ Schenkman JB, Jansson I. The many roles of cytochrome b5. Pharmacol Ther. 2003 Feb;97(2):139-52. PMID:12559387

- ↑ Rodriguez-Maranon MJ, Qiu F, Stark RE, White SP, Zhang X, Foundling SI, Rodriguez V, Schilling CL 3rd, Bunce RA, Rivera M. 13C NMR spectroscopic and X-ray crystallographic study of the role played by mitochondrial cytochrome b5 heme propionates in the electrostatic binding to cytochrome c. Biochemistry. 1996 Dec 17;35(50):16378-90. PMID:8973214 doi:10.1021/bi961895o

- ↑ Crofts AR. The cytochrome bc1 complex: function in the context of structure. Annu Rev Physiol. 2004;66:689-733. PMID:14977419 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032102.150251

- ↑ Berry EA, Huang LS, Saechao LK, Pon NG, Valkova-Valchanova M, Daldal F. X-Ray Structure of Rhodobacter Capsulatus Cytochrome bc (1): Comparison with its Mitochondrial and Chloroplast Counterparts. Photosynth Res. 2004;81(3):251-75. PMID:16034531 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:PRES.0000036888.18223.0e

- ↑ Rajagopal BS, Wilson MT, Bendall DS, Howe CJ, Worrall JA. Structural and kinetic studies of imidazole binding to two members of the cytochrome c (6) family reveal an important role for a conserved heme pocket residue. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2011 Jan 26. PMID:21267610 doi:10.1007/s00775-011-0758-y

- ↑ Morelli X, Czjzek M, Hatchikian CE, Bornet O, Fontecilla-Camps JC, Palma NP, Moura JJ, Guerlesquin F. Structural model of the Fe-hydrogenase/cytochrome c553 complex combining transverse relaxation-optimized spectroscopy experiments and soft docking calculations. J Biol Chem. 2000 Jul 28;275(30):23204-10. PMID:10748163 doi:10.1074/jbc.M909835199

- ↑ Manole A, Kekilli D, Svistunenko DA, Wilson MT, Dobbin PS, Hough MA. Conformational control of the binding of diatomic gases to cytochrome c'. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2015 Mar 20. PMID:25792378 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00775-015-1253-7

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 Stelter M, Melo AM, Pereira MM, Gomes CM, Hreggvidsson GO, Hjorleifsdottir S, Saraiva LM, Teixeira M, Archer M. A Novel Type of Monoheme Cytochrome c: Biochemical and Structural Characterization at 1.23 A Resolution of Rhodothermus marinus Cytochrome c. Biochemistry. 2008 Oct 15. PMID:18855424 doi:10.1021/bi800999g

- ↑ Than ME, Hof P, Huber R, Bourenkov GP, Bartunik HD, Buse G, Soulimane T. Thermus thermophilus cytochrome-c552: A new highly thermostable cytochrome-c structure obtained by MAD phasing. J Mol Biol. 1997 Aug 29;271(4):629-44. PMID:9281430 doi:10.1006/jmbi.1997.1181

- ↑ Soares CM, Baptista AM, Pereira MM, Teixeira M. Investigation of protonatable residues in Rhodothermus marinus caa3 haem-copper oxygen reductase: comparison with Paracoccus denitrificans aa3 haem-copper oxygen reductase. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2004 Mar;9(2):124-34. Epub 2003 Dec 23. PMID:14691678 doi:10.1007/s00775-003-0509-9

- ↑ Pereira MM, Santana M, Teixeira M. A novel scenario for the evolution of haem-copper oxygen reductases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001 Jun 1;1505(2-3):185-208. PMID:11334784

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 Karp, Gerald (2008). Cell and Molecular Biology (5th edition). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0470042175.

- ↑ Prince RC, George GN. Cytochrome f revealed. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995 Jun;20(6):217-8. PMID:7631417

- ↑ Martinez SE, Huang D, Szczepaniak A, Cramer WA, Smith JL. Crystal structure of chloroplast cytochrome f reveals a novel cytochrome fold and unexpected heme ligation. Structure. 1994 Feb 15;2(2):95-105. PMID:8081747

- ↑ Danielson PB. The cytochrome P450 superfamily: biochemistry, evolution and drug metabolism in humans. Curr Drug Metab. 2002 Dec;3(6):561-97. PMID:12369887

- ↑ Williams PA, Cosme J, Ward A, Angove HC, Matak Vinkovic D, Jhoti H. Crystal structure of human cytochrome P450 2C9 with bound warfarin. Nature. 2003 Jul 24;424(6947):464-8. Epub 2003 Jul 13. PMID:12861225 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature01862

- ↑ Tsukihara T, Aoyama H, Yamashita E, Tomizaki T, Yamaguchi H, Shinzawa-Itoh K, Nakashima R, Yaono R, Yoshikawa S. Structures of metal sites of oxidized bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase at 2.8 A. Science. 1995 Aug 25;269(5227):1069-74. PMID:7652554

- ↑ Yoshikawa S, Shinzawa-Itoh K, Nakashima R, Yaono R, Yamashita E, Inoue N, Yao M, Fei MJ, Libeu CP, Mizushima T, Yamaguchi H, Tomizaki T, Tsukihara T. Redox-coupled crystal structural changes in bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase. Science. 1998 Jun 12;280(5370):1723-9. PMID:9624044

- ↑ Atack JM, Kelly DJ. Structure, mechanism and physiological roles of bacterial cytochrome c peroxidases. Adv Microb Physiol. 2007;52:73-106. PMID:17027371 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2911(06)52002-8

- ↑ Miller MA, Shaw A, Kraut J. 2.2 A structure of oxy-peroxidase as a model for the transient enzyme: peroxide complex. Nat Struct Biol. 1994 Aug;1(8):524-31. PMID:7664080

- ↑ Yang X, Wu D, Shi J, He Y, Pinot F, Grausem B, Yin C, Zhu L, Chen M, Luo Z, Liang W, Zhang D. Rice CYP703A3, a cytochrome P450 hydroxylase, is essential for development of anther cuticle and pollen exine. J Integr Plant Biol. 2014 Oct;56(10):979-94. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12212. Epub 2014, Jul 15. PMID:24798002 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jipb.12212

- ↑ Yu D, Xu F, Shao L, Zhan J. A specific cytochrome P450 hydroxylase in herboxidiene biosynthesis. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2014 Sep 15;24(18):4511-4514. doi:, 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.07.078. Epub 2014 Aug 6. PMID:25139567 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.07.078

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 none yet