|

Introduction

Members of the organic anion transporter (OAT) family, including

OAT1, are expressed on the epithelial membrane of the kidney,

liver, brain, intestine, and placenta.[2][3] OAT1 regulates the transport

of organic anion drugs from the blood into kidney epithelial

cells by utilizing the α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) gradient across the

membrane established by the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle.[4] [5]OAT1 also plays a key role in excreting waste from organic drug metabolism and

contributes significantly to drug-drug interactions and drug disposition. However, the structural basis of specific

substrate and inhibitor transport by human OAT1 (hOAT1) has remained elusive. Here are four

cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structures of hOAT1 in its inward-facing conformation: the apo

form, the substrate (olmesartan)-bound form with different anions, and the inhibitor (probenecid)-bound

form.

Cryo-EM structure of hOAT1

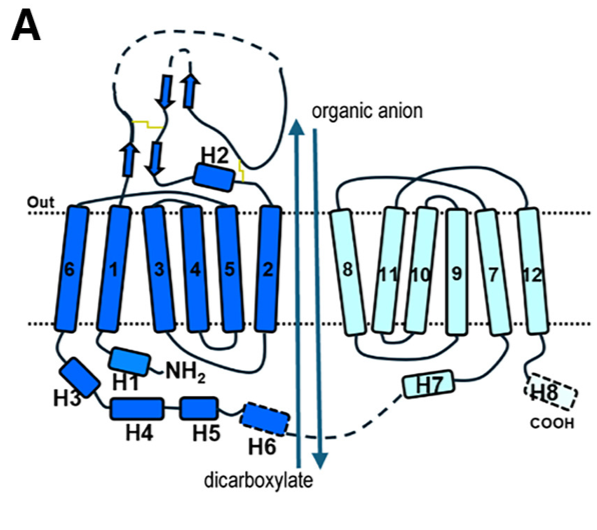

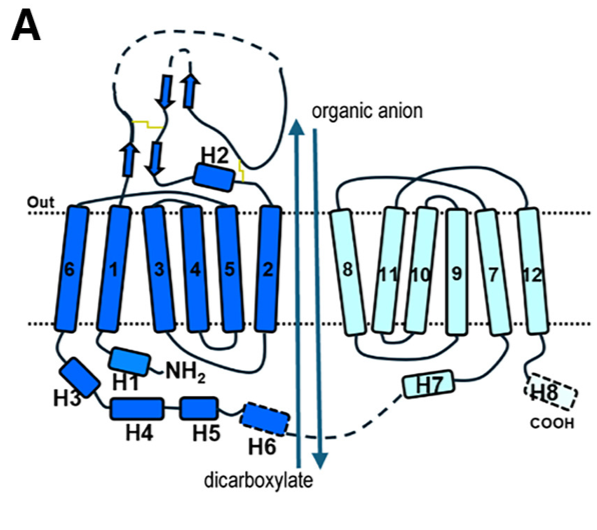

Fig 1. (A) Schematic diagram of human OAT1 topology and the overall transport process. The apo state structure of human Organic Anion Transporter 1 (hOAT1), determined by cryo-EM, reveals the transporter in an inward-facing conformation. This means the central substrate-binding cavity is open toward the intracellular side of the membrane, ready to release a substrate or accept one from the cytoplasm.

Key Structural Characteristics:

- Adopts the classic Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS) fold.

- Comprises 12 transmembrane helices (TMs 1-12).

- Exhibits pseudo-two-fold symmetry, divided into an N-lobe (TMs 1-6) and a C-lobe (TMs 7-12).

- The cavity is located between the N-lobe (formed by TM1, TM2, TM4, TM5) and the C-lobe (formed by TM7, TM8, TM10, TM11).

- It possesses a positively charged electrostatic environment, which explains its strong preference for transporting anionic substrates.

- The cavity is lined by 29 residues, forming a hydrophobic and aromatic-rich environment.

- Cavity Borders and Cytosolic Gate:

- The top border (extracellular side) of the cavity is formed by residues including N35, Y230, Y353, and Y354 and are involved in substrate recognition

- The bottom border (cytosolic side) features a narrow "thin bottom gate" formed by residues M207 and F442. The interaction between these two residues splits the cytosolic entrance into two distinct pathways:

- Path A: Located between TM2 and TM11.

- Path B: Located between TM5 and TM8.

- This suggests that aromatic residues located at the top border are important for extracellular anion binding, while residues at the bottom play a role in exporting extracellular anions to the cytoplasmic side.

- In the apo state, the transporter is in a relaxed, inward-open conformation, providing access for substrates from the cytoplasm.

Olmesartan recognition by hOAT1

The structural and functional analysis of provides a detailed blueprint for substrate specificity and binding.

1. Binding Location and Pose

- Olmesartan binds within the central cavity of hOAT1 in an inward-facing conformation.

- It occupies Site 3 of the binding pocket, which is the primary polyspecific site for anionic substrates.

- The drug adopts a diagonal orientation relative to the membrane plane, a pose that requires more space than the smaller inhibitor probenecid. This orientation is similar to its conformation when bound to the angiotensin receptor.

2. Key Interacting Residues

- Olmesartan occupies Site 3 of the binding pocket and is located within 5A˚ distance of residues of TM1, TM4, TM5, TM7, TM10, and TM11, namely N35, M207, G227, Y230, W346, Y353, Y354, F438, F442, S462, and R466.

- The biphenyl group and tetrazole ring of olmesartan rely on interactions with hydrophobic residues close to the bottom gate in the binding pocket.

- Upon olmesartan binding, the side chain of Y230 undergoes a vertical rotation to accommodate and interact with the substrate.

- M207 and F442 residues forming the bottom gate of the binding pocket affect olmesartan interactions

Mechanism of OAT1 inhibition by probenecid

The cryo-EM structure of reveals a dual-mechanism of action that goes beyond simple competition, effectively arresting the transporter in a restricted state.

1. Binding Mode and Direct Competition

- Probenecid binds at the top of the central cavity, parallel to the membrane plane.

- Its binding site overlaps with both Site 1 (partially) and Site 3.

- In the binding pocket of Site 1, surrounded by 16 residues located within a 5 A ˚ (M31, N35, M142, V145, G227, Y230, W346, Y353, Y354, K382, D378, F438, S462, A465, R466, and S469).

- It engages in specific, high-affinity interactions with key residues:

- K382 on TM8 forms a hydrogen bond with the carboxylate group of probenecid.

- Y354 on TM7 forms a hydrogen bond with its sulfonyl group.

- Crucially, K382 is also the residue that interacts with the counter-substrate α-ketoglutarate (α-KG), establishing a direct competitive inhibition mechanism by blocking α-KG binding.

2. Conformational Arrest and Cytoplasmic Path Blockage

The primary inhibitory mechanism is a probenecid-induced conformational change that physically blocks substrate access and exit.

- Constriction of the Binding Pocket: Compared to the apo state, the cytoplasmic opening of the binding pocket narrows from ~15 Å to ~12 Å in the probenecid-bound state.

- Dual-Pathway Blockade: The cytosolic entrance is split into two paths. Probenecid binding critically affects both:

- Path A (between TM2 and TM11) is narrowed from ~5 Å to ~4 Å.

- Path B (between TM5 and TM8) is completely blocked. Restriction of the access route to path B likely limits the entry of substrates to Site 1 and the exit of substrates from the binding pocket.

This structural rearrangement is caused by a slight inward movement of the cytoplasmic ends of TM5, TM8, TM10, and TM11 toward the binding pocket.

3. Locked Conformation

By constricting the cytoplasmic access routes, probenecid does not just compete for the substrate-binding site; it stabilizes the transporter in an apo-like, inward-facing conformation that is inaccessible to cytosolic substrates. This prevents the entry of new substrates and likely traps the transporter in this non-functional state, effectively "locking" it and preventing the conformational changes necessary for the transport cycle.

Full Mechanism of Binding and Inhibition in hOAT1

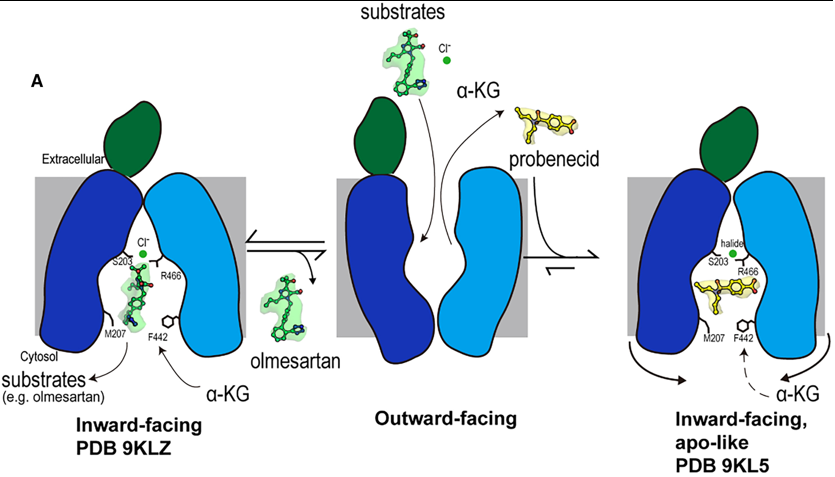

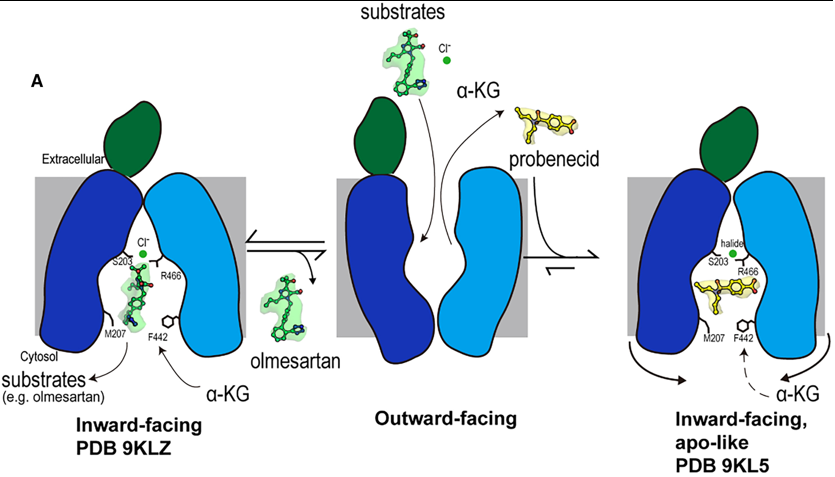

Fig 2. Mechanism of olmesartan binding and conformational inhibition by probenecid. A) When the transporter is in its outward-facing conformation, substrates or inhibitors enter the central binding pocket and undergo structural rearrangement to the inward-facing conformation. When olmesartan interacts with the bottom gating residues M207 and F442, the side chains S203, Y230 (not shown here), and R466 appear to rearrange to coordinate with a chloride ion and drug compared to the apo structure. Whereas probenecid binding induces an additional conformation change for inhibition (apo-like conformation). Overall Transport Cycle & Substrate Binding (e.g., Olmesartan)

1. Outward-Facing State (Hypothesized): The transport cycle begins with the transporter in an outward-facing conformation, open to the extracellular space. Substrates and inhibitors from the blood enter the central binding pocket at this stage.

2. Transition to Inward-Facing State: Upon binding a substrate like olmesartan, the transporter undergoes a conformational change to the inward-facing state, which is the conformation captured in this study.

3. Substrate Binding and Chloride Coordination in the Inward-Open State:

- Olmesartan docks into Site 3, the polyspecific substrate-binding site, engaging a cage of hydrophobic and aromatic residues (e.g., F438, Y354).

- Its binding induces specific structural rearrangements, most notably a vertical rotation of the Y230 side chain.

- Crucially, olmesartan binding creates a favorable environment for chloride ion coordination. The chloride ion is stabilized by a network involving S203, the rotated Y230, and R466.

- This chloride coordination, facilitated by the species-specific residue S203, is essential for high-affinity binding and efficient translocation of olmesartan. The bottom-gate residues M207 and F442 also interact with the drug, potentially playing a role in its final release into the cytoplasm.

4. Substrate Release: The inward-facing conformation with its open paths (Path A and Path B) allows the substrate to dissociate into the cytoplasm. The transporter then likely resets to the outward-facing state, driven by the exchange with intracellular α-ketoglutarate (α-KG).

Inhibition Mechanism (e.g., Probenecid)

The inhibitor probenecid exploits the transport cycle but arrests it through a dual mechanism:

1. Binding and Competition:

- Probenecid enters the binding pocket from the extracellular side and binds in the inward-facing conformation.

- It occupies Site 3 and partially extends into Site 1. In Site 1, it directly competes with the counter-substrate α-KG by forming a key hydrogen bond with K382, a residue critical for α-KG binding.

2. Conformational Arrest and Cytoplasmic Blockade:

- This is the primary inhibitory mechanism. Probenecid binding induces subtle but critical conformational changes in the cytoplasmic regions of TM5, TM8, TM10, and TM11.

- These helices shift inward, causing a constriction of the entire cytoplasmic opening of the binding pocket.

- This constriction completely blocks Path B and severely narrows Path A.

- By physically obstructing these cytosolic paths, probenecid achieves two things:

- It prevents intracellular substrates from entering the binding pocket.

- It traps the transporter in a locked, inward-facing, apo-like conformation, preventing the conformational changes needed to complete the transport cycle.

Author

Kaushki Sharma

Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Pune, India

BI3323-Aug2025

Notes & References

- ↑ Cryo-EM structures of human OAT1 reveal drug

binding and inhibition mechanisms https://doi.org/10.1016/j.str.2025.07.019

- ↑ Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel liver-specific transport protein https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.107.4.1065

- ↑ Molecular Cloning and Characterization of NKT, a Gene Product Related to the Organic Cation Transporter Family That Is Almost Exclusively Expressed in the Kidney https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.272.10.6471

- ↑ Ingraham, L., Li, M., Renfro, J.L., Parker, S., Vapurcuyan, A., Hanna, I., and

Pelis, R.M. (2014). A plasma concentration of α-ketoglutarate influences

the kinetic interaction of ligands with organic anion transporter 1. Mol.

Pharmacol. 86, 86–95. https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.114.091777.

- ↑ Uwai, Y., Kawasaki, T., and Nabekura, T. (2017). D-Malate decreases renal

content of α-ketoglutarate, a driving force of organic anion transporters

OAT1 and OAT3, resulting in inhibited tubular secretion of phenolsulfonphthalein,

in rats. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 38, 479–485. https://doi.org/10.

1002/bdd.2089.

|