Sandbox 48

From Proteopedia

Template:Tims Sandbox Reservation

|

Contents |

General Preliminary Information and Historical Development

Lysozyme is an enzyme known for its unique ability to degrade the polysaccharide architecture of many kinds of cell walls, normally for the purpose of protection against bacterial infection[1]. In avian species, lysozyme is an abundant component of egg white (the general image of lysozyme for this page is of Hen Egg White [HEW] Lysozyme), in which lysozyme functions as an antibiotic and as a nutrient for early embryogenesis [2]. In vertebrate species, lysozyme is generally found in mucosal secretions, such as tears and saliva, and functions in the same way that it functions in avian species for antibacterial purposes.

The discovery of lysozyme in 1922 by Alexander Fleming was providential in that the undertaken experiment related to the discovery of lysozyme was not geared toward any knowledge of such a protein as lysozyme [3]. During the unrelated experiment, nasal drippings were inadvertently introduced to a petri dish containing a bacterial culture, which culture consequently exhibited the results of an as yet unknown enzymatic reaction. The observation of this unknown reaction led to further research on the components of this reaction as well as to the corresponding identification of the newfound "lysozyme." Fleming's discovery was complemented by David C. Phillips' 1965 description of the three-dimensional structure of lysozyme via a 200pm resolution model obtained from X-ray crystallography [4]. Phillips' work was especially groundbreaking since, by successfully elucidating the structure of lysozyme via X-ray crystallography, Phillips had managed to successfully elucidate the structure of an enzyme via X-ray crystallography - a feat that had never before been accomplished[5]. Phillips' research also led to the first sufficiently described enzymatic mechanism of catalytic action [6]. Thus, Phillips' elucidation of the function of lysozyme led Phillips to reach a more general conclusion on the diversity of enzymatic chemical action in relation to enzymatic structure. Clearly, the findings of Phillips as well as the more general historical development of the understanding of the structure and function of lysozyme have been paramount to the more general realm of enzyme chemistry.

General Function

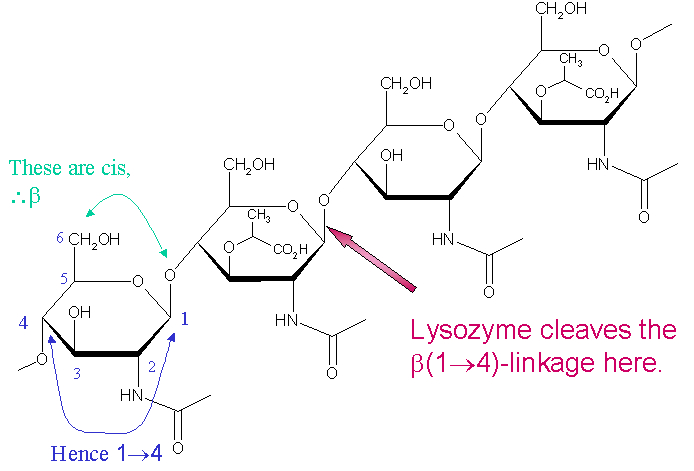

Lysozyme is a 129 amino acid-long enzyme - the HEW lysozyme shown is composed of six distinct α-helix regions (eight helix units) and three distinct β-sheets, which seem to occur cooperatively in a hairpin-like motif (In the following variation of the general image of HEW lysozyme for this page, the α-helices are highlighted as black, and the β-sheets are highlighted as red. All non-characteristic secondary turns and bends maintain the base color. . However, HEW lysozyme may have five, six, seven or eight alpha helices depending on its original locational architecture [7]) - that is particularly specific in its cleavage proclivity for alternating polysaccharide copolymers of N-acetyl glucosamine (NAG) and N-acetyl muramic acid (NAM) (the standard ligand construction for lysozyme), which architectural theme represents the "unit" polysaccharide structure of many bacterial cell walls [8]. The location of cleavage for lysozyme on this architectural theme is the β(1-4) glycosidic linkage connecting connecting the C1 carbon of NAM to the C4 carbon of NAG.

[9]

[9]

The particular substrate of preference for this cleavage type is a (NAG-NAM)₃ hexasaccharide, within which substrate occurs the cleaving target glycosidic bond of NAM₄-β-O-NAG₅. The individual hexasaccharide binding units are designated A-F, with the NAM₄-β-O-NAG₅ glycosidic bond cleavage preference corresponding to a D-E unit glycosidic bond cleavage preference.

Mechanism of Action

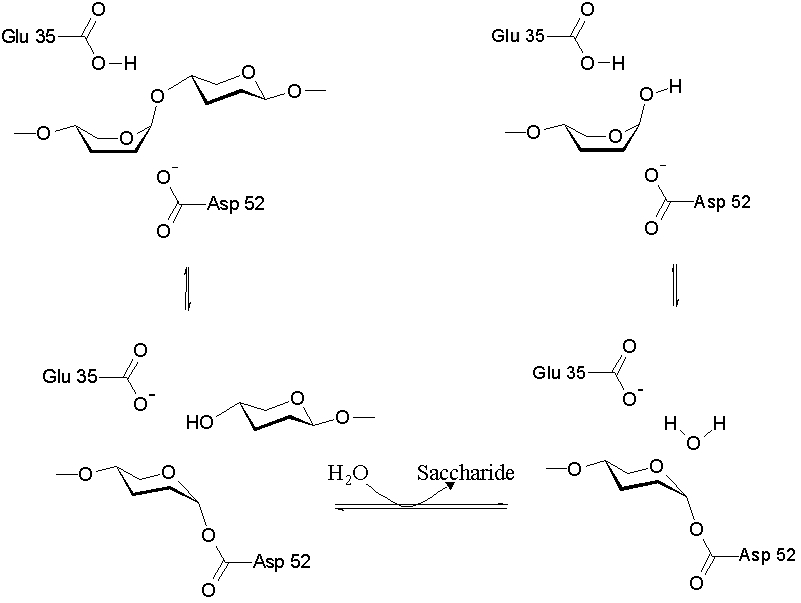

The lysozyme mechanism of action results in the hydrolysis of a glycoside (hence the familial distinction of lysozyme as a glycosylase[10]), which corresponds to the conversion of an acetal to a hemiacetal, which reaction (general degradation of glycosidic bond to units "capped" by newly formed hydroxyl groups) necessitates acid catalysis, since the conversion of acetal to hemiacetal involves the protonation of the reactant oxygen prior to actual bond cleavage. [11]. Furthermore, the transition state obtained from this protonation is a covalent, oxonium ion, intermediate that must obtain resonance stabilization. The need for some means of acid catalysis and covalent resonance stabilization is adequately provided by the Glu 35 and Asp 52 residues of lysozyme, respectively. The reaction mechanism of lysozyme is demonstrated. In the following image, the reaction begins at the upper left-hand side, and proceeds according to reaction arrows.

The action of Glu 35 in providing a means of acid catalysis (via protonation of the reactant oxygen) and the action of Asp 52 in providing covalent resonance stabilization of the oxonium ion are clearly demonstrated in this image.

Architectural Features Beyond Secondary Structure

The active site of lysozyme is formulated as a prominent cleft outlined by the two aforementioned catalytic enzymes, Glu 35 and Asp 52. In the following variation of the general image of HEW lysozyme for this page, Glu 35 is highlighted as red, and Asp 52 is highlighted as black . The position of these two residues in the active site cleft allows for the ultimate and proper positioning of the polysaccharide D-E unit for cleavage.

The distribution of polar residues in juxtaposition to the distribution of non-polar residues is shown in the following variation of the general image of HEW lysozyme for this page. All polar residues are highlighted as black, all nonpolar residues maintain the base color . As may be inferred from this scene, the occurrence of polar residues in lysozyme is roughly equivalent to the occurrence of non-polar residues in lysozyme. Although not specifically indicated in this scene, a manifestation of the distribution of polarity in lysozyme occurs in the juxtaposition of the situations of the catalytic residues Glu 35 and Asp 52. While Glu 35 is located in a primarily non-polar, hydrophobic region of architecture, Asp 52 is located in a heavily polarized region of architecture [13]. Because of the situation of Glu 35, the pH of the carboxyl group of Glu 35 is unusually high and, thus, remains protonated so that Glu 35 can act as the acid catalyst necessary for acetal hydrolysis. Likewise, the situation of Asp 52 results in the formation of multiple hydrogen bonds between Asp 52 and its highly polar environment, which, in turn, results in the retention of a normal pK value for Asp 52, leaving the residue in its normal unprotonated, negatively-charged state. Because of this phenomenon, Asp 52 is able to electrostatically stabilize the oxonium ion intermediate - Asp 52 is able to act as the necessary covalent resonance stabilizer for acetal hydrolysis. The situation of Glu 35 and Asp 52 is indicated in the following variation of the general image of HEW lysozyme for this page. In this image, Glu 35 is highlighted as red, Asp 52 is highlighted as black and all polar residues are highlighted as dark pink .

Disulfide bonds are present in four locations on HEW lysozyme: between Cys 6 and Cys 127, between Cys 30 and Cys 115, between Cys 64 and Cys 80 and between Cys 76 and Cys 94 [14]. In the following variation of the general image of HEW lysozyme for this page, all cysteine residues are highlighted as black. All disulfide bonds arising from Cys-Cys interactions are highlighted as yellow .

Hydrogen bond interactions are vital to the general orientation of lysozyme. This fact is clearly demonstrated in the structure of HEW lysozyme. In the following variation of the general image of HEW lysozyme for this page, all constant hydrogen bonds are highlighted as red . The hydrogen network arrangement clearly indicates the importance of hydrogen bonding for architectural retention in lysozyme.

References

- ↑ Lysozyme. 2010. Citizendium.org. http://en.citizendium.org/wiki/Lysozyme

- ↑ Sears, D.W. 2010. Overview of the Structure and Function of Hen Egg-White Lysozyme. Ucsb.edu. http://mcdb-webarchive.mcdb.ucsb.edu/sears/biochemistry/tw-enz/lysozyme/HEWL/lysozyme-overview.htm/

- ↑ Lysozyme. 2008. Lysozyme.co.uk. http://lysozyme.co.uk/

- ↑ Lysozyme, 2008. Lysozyme.co.uk. http://lysozyme.co.uk/

- ↑ Bugg, T. 1997. An Introduction to Enzyme and Coenzyme Chemistry. Blackwell Science Ltd., Oxford

- ↑ 1967. Proc R Soc Lond B Bio 167 (1009): 389–401.

- ↑ Walshaw, J. 1995. Lysozyme. Cryst.bbk.ac.uk. http://www.cryst.bbk.ac.uk/PPS95/course/10_interactions/lysozyme.html

- ↑ Sears, D.W. 2010. Overview of the Structure and Function of Hen Egg-White Lysozyme. Ucsb.edu. http://mcdb-webarchive.mcdb.ucsb.edu/sears/biochemistry/tw-enz/lysozyme/HEWL/lysozyme-overview.htm/

- ↑ Image from: http://www.vuw.ac.nz/staff/paul_teesdale-spittle/essentials/chapter-6/proteins/lysozyme.htm

- ↑ Lysozyme, 2008. Lysozyme.co.uk. http://lysozyme.co.uk/

- ↑ Pratt, C.W., Voet, D., Voet, J.G. Fundamentals of Biochemistry - Life at the Molecular Level - Third Edition. Voet, Voet and Pratt, 2008.

- ↑ Image from: http://www.google.com/imgres?imgurl=http://www.vuw.ac.nz/staff/paul_teesdale-spittle/essentials/chapter-6/pics-and-strucs/lysozyme-mech.gif&imgrefurl=http://www.vuw.ac.nz/staff/paul_teesdale-spittle/essentials/chapter-6/proteins/lysozyme.htm&usg=__ormapG4XKg-tR5GrMSOdSMTV4vE=&h=603&w=801&sz=7&hl=en&start=17&zoom=1&tbnid=nvr9gvFrUILDkM:&tbnh=143&tbnw=189&prev=/images%3Fq%3DThe%2Blysozyme%2Breaction%2Bmechanism%26um%3D1%26hl%3Den%26sa%3DN%26biw%3D1280%26bih%3D647%26tbs%3Disch:10%2C304&um=1&itbs=1&iact=hc&vpx=521&vpy=349&dur=448&hovh=191&hovw=254&tx=140&ty=48&ei=JQ_LTPKzLIjCsAPkzt2KDg&oei=IA_LTP74OsG78gapm-GFAQ&esq=2&page=2&ndsp=18&ved=1t:429,r:2,s:17&biw=1280&bih=647

- ↑ Pratt, C.W., Voet, D., Voet, J.G. Fundamentals of Biochemistry - Life at the Molecular Level - Third Edition. Voet, Voet and Pratt, 2008.

- ↑ 2001. Lysozyme. Rcn.com. http://users.rcn.com/jkimball.ma.ultranet/BiologyPages/L/Lysozyme.html