From Proteopedia

proteopedia linkproteopedia link

Histone Deacetylase 8 (HDAC 8)

Introduction

Histone deacetylase 8 (HDAC8) is an enzyme that plays a role in controlling gene expression in Homo sapiens. Specifically, HDAC8 catalyzes the removal of an acetyl group off of the ε-amino-lysine sidechain of N-terminal core of histones. Histones consist of eight monomers to form an octomer complex. In addition, histones are highly basic and have a large positive charge. Since DNA is negatively charged, histones tightly interact with DNA. This prevents transcription factors from accessing DNA, thus decreasing gene expression. Chromatin remodeling by histone acetylation and/or deacetylation is an example of epigenetic regulation. HATs catalyze the addition of an acetyl group onto a histone. The hydrophobicity of the acetyl group prevents the interaction between DNA and histones. This allows transcription factors to access the DNA to increase gene expression. HDAC8 though reverses this reaction by catalyzing the removal of these acetyl groups by removing the acetate and the reclaimed positive charge on the lysine sidechain is able to interact with the negative charge on the DNA. As a result, DNA will bind more tightly to the histone protein, repressing transcription and gene expression.

|

Homology

There are four major classes of HDAC proteins (I,II, III, and IV). Other than the Class III “Sirtuins” which utilize a NAD+ cofactor-dependent mechanism, all other HDAC classes use Zn2+-assisted catalysis through mechanisms reminiscent of a typical serine protease.*,** While Classes I, II, and IV do have some major distinctions such as size of peptide (see Table), they retain a great degree of homology both between and within classes, especially at catalytic sites.** HDAC 8 is among the Class I HDACs alongside HDACs 1-3. It shares a high degree of conserved residues involved in the catalytic site, Zn-binding, and ligand binding pocket.** (Big letter picture)

Classes

Sequence Alignment

Structural Highlights

The HDAC8 comprises a single α/β domain that is composed of an eight-stranded parallel sandwiched between 13 . The HDAC8 consists of 377 amino acids, half of which are contained in the secondary structure elements and the other half are contained in loops that link the various elements of the secondary structure. The residues forming active site and catalytic machinery of the enzyme is found in the loops from the C-terminal ends of the strands of the core β-sheet. [1]

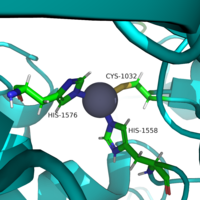

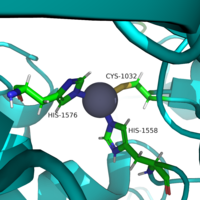

Zinc Ion

The pentacoordinated Zn2+ ion involved in the metalloenzyme catalysis is tethered to the protein through interactions with . This positions the metal ion to favorably interact the catalytic water and acetylated lysine substrate. ** The zinc ion lowers the pKa of a water proton that makes the water more nucleophilic. Besides increasing the nucleophilicity of the zinc, the zinc like also facilitates the deacetylation process by reducing the entropy of the reaction by binding both the nucleophile and the substrate and polarizing the carbonyl of the acetyl-lysine and stabilizing the transition state.[1]

Key Residues

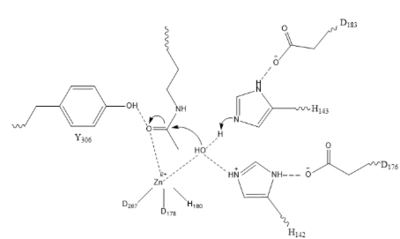

The of HDAC8 is composed of 2 catalytic dyads: Asp183/H143 and Asp176/His142, which activate the catalytic water nucleophile. A Tyr306, through mutation to Phe in the pdb file 2v5w (modeled in the overall view) was observed to render the protein mostly inactive. Thus, it has been hypothesized that the this residue is critical to transition state stabilization with the Zn2+ ion.

Similar to many serine and zinc proteases, HDAC8 uses a mechanism with a "catalytic triad." Instead of the Asp-His-Ser, HDAC8 uses the His to coordinate a H2O nucleophile. Binding Pocket

By encasing, the nonpolar 4 carbon-long side chain of the Lys residue on the Ligand, Phe152 and Phe208 engage in hydrophobic Van der Waals with the ligand. & At different ends of the , W141 and M274 contribute to the overall shape through general hydrophobic interactions.*** Finally, the carbonyl O of Gly151 hydrogen bonds with the amide H of the acetylated lysine to further interact with the ligand in the relatively hydrophobic tunnel.**

Asp 101

At the rim of the active site, is involved in two hydrogen bonds between its own carbonyl Os and two consecutive amide Hs of incoming . This forces the ligand to assume a cis-conformation. In addition, extensive interactions among many other polar atoms near the rim of the active site help keep the ligand lodged in the hydrophobic tunnel.**

Active site loop

(amino acid residues 30-36) lines a large portion of one face of the active site pocket and extends to the protein surface. This results in a larger surface opening of the active site pocket. It is suggested that this loop has high flexibility, making the active site pocket opening highly malleable and able to change to accommodate binding to a variety of different ligands.

Mechanism

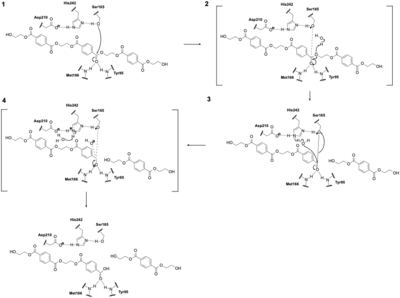

Once bound to the binding pocket through interactions with Asp101, Phe153, and Phe208, the water molecule nucleophilically attacks the carbonyl carbon of the ε-amino-lysine sidechain of N-terminal core of histone proteins. This water molecule is recruited and stabilized by two catalytic dyads. The first dyad consists of His143 and Asp183. Asp183 interacts with His143 to shift electron density so that His143 may act as a general base to remove a proton from water. The second catalytic dyad consists of His142 and Asp176 and stabilizes the now deprotonated water molecule. A Zn2+ ion also makes the water more nucleophilic by drawing positive character away from the water. The tetrahedral intermediate is stabilized by the Zn2+ ion as well as Tyr306. The amine group of the histones lysine residue acts as a general base and deprotonates His143. This drives the tetrahedral intermediate to collapses and expel the acetyl group to produce an acetate ion and a deacetylated lysine residue.

|

Relevance

Besides controlling the gene regulation through deacetylation of histones, HDAC 8 also regulates the post-transcriptional acetylation status of many non-histone proteins, including transcription factors, chaperones, hormone receptors and signaling molecules. Thus, it has influences on protein stability, protein-protein interactions and protein-DNA interactions. HDAC 8 can therefore affect the regulation of cell proliferation and cell death. These processes are typically being altered in cancer cells and that makes HDAC enzymes an interesting potential target for cancer drugs. HDAC inhibitors have been shown to be promising cancer drug agents in prior research as the HDAC inhibitors cease tumor growth in cancer cells by either making them differentiate, undergo apoptosis or upregulate cell cycle arrest proteins. [2]. One way, the HDAC inhibitors ceases tumor growth is by the reactivation of the transcription factor,RUNX3, a known tumor suppressor. HDACi increases the acetylation of the protein and as the stability of RUNX3 is dependent on the acetylation status of the protein, the increased acetylation or HDAC inhibition will enhance the protein stability, causing an increase in the anti-tumorous properties of the protein. A number of HDAC inhibitors have been purified from natural sources or synthesized and HDAC inhibitors can be structurally grouped into at least four classes: hydrox-amates, cyclic peptides, aliphatic acids and ben-zamides. The Vorinostat(within the hydroxamate class) has been FDA-approved for treatment of cancer. The hydroxamate HDAC inhibitors consists of a metal-binding domain, a linker domain and a hydrophobic capping group. The HDAC class 1 hydroxamic acid, compound 1, fashion in a bidendate fashion while making hydrogen bonds to important residues as at the active site of HDAC8. Thus, the HDAC inhibitors can be used as antagonists to prevent the functioning of HDAC8 in cancer treatment. [3]

References

1. Whitehead, L., Dobler, M. R., Radetich, B., Zhu, Y., Atadja, P. W., Claiborne, T., ... & Shao, W. (2011). Human HDAC isoform selectivity achieved via exploitation of the acetate release channel with structurally unique small molecule inhibitors. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry, 19(15), 4626-4634.

Eckschlager, T., Plch, J., Stiborova, M., & Hrabeta, J. (2017). Histone deacetylase inhibitors as anticancer drugs. International journal of molecular sciences, 18(7), 1414.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.str.2004.04.012

- ↑ https://dx.doi.org/10.3390%2Fijms18071414

- ↑ https://dx.doi.org/10.1073%2Fpnas.0404603101

Somoza, J. R., Skene, R. J., Katz, B. A., Mol, C., Ho, J. D., Jennings, A. J., ... & Tang, J. (2004). Structural snapshots of human HDAC8 provide insights into the class I histone deacetylases. Structure, 12(7), 1325-1334.

Vannini A, Volpari C, Filocamo G, Casavola EC, Brunetti M, Renzoni D, Chakraarty P, Paolini C, De Francesco R, Gallinari P, Steinkuhler C and Di Marco S. Crystal structure of a eukaryotic zinc-dependent histone deacetylase, human HDAC8, complexed with a hydroxamic acid inhibitor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004.