| OCT4-SOX2-bound nucleosome - SHL-6</scene>

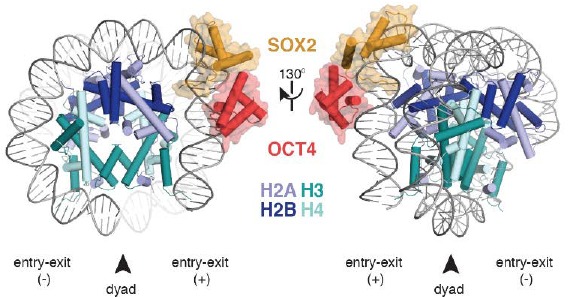

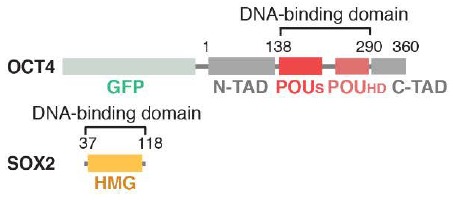

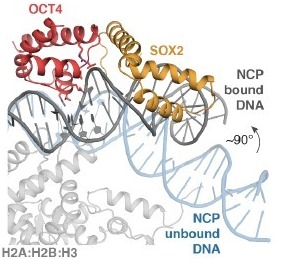

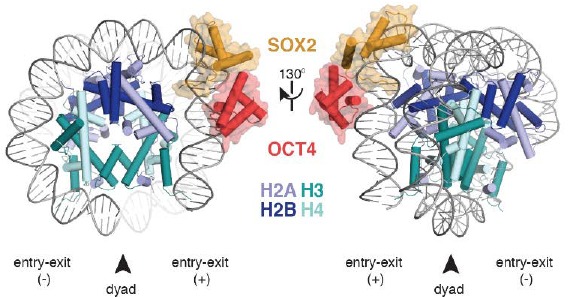

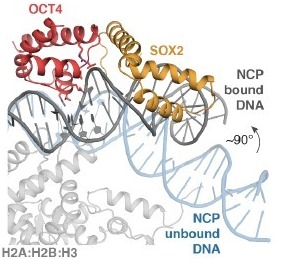

OCT4 recognizes a partial motif, engaging DNA with its POUS domain, whereas the POUHD is not engaged [30]. On free DNA, both POU domains engage the major groove over 8bp on opposite sides of the DNA [31]. SOX2 competes with histones for DNA binding and kinks DNA by ~90° at SHL-6.5 away from the histones (Fig.3)[30] [23]. This is accomplished by intercalation of the SOX2 Phe48 and Met49 ‘wedge’ at the TT base step [23]. SOX2 kinks the DNA and synergistically with OCT4 releases the DNA from the core histones (Movie1[30]).

Figure 1 - OCT4-SOX2-NCPSHL+6 model[30].

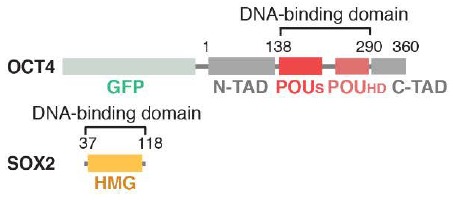

Figure 2 - Domain schematic of OCT4 and SOX2 constructs[30].

Figure 3 - OCT4 SOX2 lifts the entry exit DNA away from the histone core. Comparison of the unbound nucleosome DNA (blue) with the OCT4-SOX2 bound nucleosome structure (grey). The DNA is kinked ~90° away from the histones. Residues at the OCT4-DNA interface are shown in sticks. POUS motif nucleotides are shown as ribose and base rings[30].

Gatekeeper for embryonic stem cell pluripotency

The pluripotent identity is ruled by transcriptional factor such as Oct4 and Sox2, that act as key pluripotency regulators among the mammals [3]. Oct4 keeps the undifferentiated cells from becoming trophoblast or endoderm [3] and Sox2 is critical in the formation of pluripotent epiblast cells [32]. The forced expression of Oct4 in Sox2-null mouse embryonic stem cells can rescue the pluripotency, indicating that the role of Sox2 in maintaining the pluripotent state of embryonic stem cells is primarily to sustain a sufficient level of Oct4 expression [28] [29]. Oct4 and Sox2 cooperate to keep the pluripotency of embryonic stem cells by co-occupying a large number of enhancers and/or promoters and regulating the expression levels of their target genes [32]. They activate the transcription of genes involved in the self renewal of embryonic stem cells and besides, they bind themselves to the promoters of their own genes activating them [3].

Yamanaka reprogramming factors and Induced Pluripotend Stem Cells (iPSCs)

In 2006, Yamanaka and Takahashi first demonstrated the factors necessary for the induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSC) generation. The Yamanaka factors, including Oct3/4 and Sox2 (also Klf4 and c-Myc), represent an important milestone in life sciences and have been widely used in the research and medical fields [33]. iPSCs are a type of pluripotent stem cell that can be generated directly from a somatic cell, usually derived from skin or blood cells, that have been reprogrammed through the introduction of four specific genes ( Oct3/4, Sox2, Myc,and Klf4) encoding transcription factors[34]. Since iPSCs can propagate indefinitely, as well as give rise to every other cell type in the body (such as neurons, heart, pancreatic, and liver cells), they represent a single source of cells that could be used to replace those lost to damage or disease, bringing a promise in the field of regenerative medicine[35].

Related Diseases

Eye Disorders

Mutations in the SOX2 gene have been linked with several eye disorders. An example is bilateral anophthalmia, a severe structural eye deformity. This syndrome is a rare disorder characterized by abnormal development of the eyes and other parts of the body. People with SOX2 anophthalmia syndrome are usually born without eyeballs (anophthalmia), although some individuals have small eyes (microphthalmia); another related disease in this field is septo-optic dysplasia (SOD), a condition characterized by midline and forebrain abnormalities, optic nerve and pituitary hypoplasia[36].

Tumorigenicity

Since these factors are straightly related to pluripotency regulation in stem cells, it has been documented that an aberrant expression of this TF's, together or separately, lead to tumorigenesis, metastasis and even greater recurrence after treatments in different types of cancer [3]. The increased expression of OCT4 was correlated with poorer survival and greater aggressiveness in bladder tumors[3] hepatocellular carcinoma[37], breast[38], pancreas[39], among others. Also, in a recent study, a significant correlation was reported between lower survival of patients with Medulloblastoma, a pedriadic brain tumor, and aberrant expression of the POU5F1 gene[40]. Another study also reported that increased levels of OCT4A in Medulloblastoma cells stimulate their tumorigenic properties, such as cell proliferation and invasion, generation of neurospheres and metastatic capacity, which indicates that these high levels of OCT4A are related with greater tumor aggressiveness[6].

References

- ↑ Boyer LA, Lee TI, Cole MF, Johnstone SE, Levine SS, Zucker JP, Guenther MG, Kumar RM, Murray HL, Jenner RG, Gifford DK, Melton DA, Jaenisch R, Young RA. Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2005 Sep 23;122(6):947-56. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.020. PMID:16153702 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.020

- ↑ Chen X, Xu H, Yuan P, Fang F, Huss M, Vega VB, Wong E, Orlov YL, Zhang W, Jiang J, Loh YH, Yeo HC, Yeo ZX, Narang V, Govindarajan KR, Leong B, Shahab A, Ruan Y, Bourque G, Sung WK, Clarke ND, Wei CL, Ng HH. Integration of external signaling pathways with the core transcriptional network in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2008 Jun 13;133(6):1106-17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.043. PMID:18555785 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.043

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Zeineddine D, Hammoud AA, Mortada M, Boeuf H. The Oct4 protein: more than a magic stemness marker. Am J Stem Cells. 2014 Sep 5;3(2):74-82. eCollection 2014. PMID:25232507

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Malakootian M, Mirzadeh Azad F, Naeli P, Pakzad M, Fouani Y, Taheri Bajgan E, Baharvand H, Mowla SJ. Novel spliced variants of OCT4, OCT4C and OCT4C1, with distinct expression patterns and functions in pluripotent and tumor cell lines. Eur J Cell Biol. 2017 Jun;96(4):347-355. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2017.03.009. Epub, 2017 Apr 10. PMID:28476334 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcb.2017.03.009

- ↑ Wang X, Dai J. Concise review: isoforms of OCT4 contribute to the confusing diversity in stem cell biology. Stem Cells. 2010 May;28(5):885-93. doi: 10.1002/stem.419. PMID:20333750 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/stem.419

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 da Silva PBG, Teixeira Dos Santos MC, Rodini CO, Kaid C, Pereira MCL, Furukawa G, da Cruz DSG, Goldfeder MB, Rocha CRR, Rosenberg C, Okamoto OK. High OCT4A levels drive tumorigenicity and metastatic potential of medulloblastoma cells. Oncotarget. 2017 Mar 21;8(12):19192-19204. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15163. PMID:28186969 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.15163

- ↑ Villodre ES, Kipper FC, Pereira MB, Lenz G. Roles of OCT4 in tumorigenesis, cancer therapy resistance and prognosis. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016 Dec;51:1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.10.003. Epub 2016 Oct, 14. PMID:27788386 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.10.003

- ↑ Atlasi Y, Mowla SJ, Ziaee SA, Gokhale PJ, Andrews PW. OCT4 spliced variants are differentially expressed in human pluripotent and nonpluripotent cells. Stem Cells. 2008 Dec;26(12):3068-74. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0530. Epub 2008 , Sep 11. PMID:18787205 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1634/stemcells.2008-0530

- ↑ Hatefi N, Nouraee N, Parvin M, Ziaee SA, Mowla SJ. Evaluating the expression of oct4 as a prognostic tumor marker in bladder cancer. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2012 Nov;15(6):1154-61. PMID:23653844

- ↑ Schepers GE, Teasdale RD, Koopman P. Twenty pairs of sox: extent, homology, and nomenclature of the mouse and human sox transcription factor gene families. Dev Cell. 2002 Aug;3(2):167-70. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00223-x. PMID:12194848 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00223-x

- ↑ Bowles J, Schepers G, Koopman P. Phylogeny of the SOX family of developmental transcription factors based on sequence and structural indicators. Dev Biol. 2000 Nov 15;227(2):239-55. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9883. PMID:11071752 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/dbio.2000.9883

- ↑ Schaefer T, Lengerke C. SOX2 protein biochemistry in stemness, reprogramming, and cancer: the PI3K/AKT/SOX2 axis and beyond. Oncogene. 2020 Jan;39(2):278-292. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-0997-x. Epub 2019 Sep, 2. PMID:31477842 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41388-019-0997-x

- ↑ Nakagawa M, Koyanagi M, Tanabe K, Takahashi K, Ichisaka T, Aoi T, Okita K, Mochiduki Y, Takizawa N, Yamanaka S. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without Myc from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nat Biotechnol. 2008 Jan;26(1):101-6. doi: 10.1038/nbt1374. Epub 2007 Nov 30. PMID:18059259 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nbt1374

- ↑ Takeda J, Seino S, Bell GI. Human Oct3 gene family: cDNA sequences, alternative splicing, gene organization, chromosomal location, and expression at low levels in adult tissues. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992 Sep 11;20(17):4613-20. PMID:1408763

- ↑ Henderson JK, Draper JS, Baillie HS, Fishel S, Thomson JA, Moore H, Andrews PW. Preimplantation human embryos and embryonic stem cells show comparable expression of stage-specific embryonic antigens. Stem Cells. 2002;20(4):329-37. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.20-4-329. PMID:12110702 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1634/stemcells.20-4-329

- ↑ Verlinsky Y, Morozov G, Verlinsky O, Koukharenko V, Rechitsky S, Goltsman E, Ivakhnenko V, Gindilis V, Strom CM, Kuliev A. Isolation of cDNA libraries from individual human preimplantation embryos. Mol Hum Reprod. 1998 Jun;4(6):571-5. doi: 10.1093/molehr/4.6.571. PMID:9665340 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/molehr/4.6.571

- ↑ Abdel-Rahman B, Fiddler M, Rappolee D, Pergament E. Expression of transcription regulating genes in human preimplantation embryos. Hum Reprod. 1995 Oct;10(10):2787-92. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a135792. PMID:8567814 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a135792

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Fujii T, Sakurai N, Osaki T, Iwagami G, Hirayama H, Minamihashi A, Hashizume T, Sawai K. Changes in the expression patterns of the genes involved in the segregation and function of inner cell mass and trophectoderm lineages during porcine preimplantation development. J Reprod Dev. 2013;59(2):151-8. doi: 10.1262/jrd.2012-122. Epub 2012 Dec 20. PMID:23257836 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1262/jrd.2012-122

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Cauffman G, Van de Velde H, Liebaers I, Van Steirteghem A. Oct-4 mRNA and protein expression during human preimplantation development. Mol Hum Reprod. 2005 Mar;11(3):173-81. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah155. Epub 2005 Feb , 4. PMID:15695770 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/molehr/gah155

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Nichols J, Zevnik B, Anastassiadis K, Niwa H, Klewe-Nebenius D, Chambers I, Scholer H, Smith A. Formation of pluripotent stem cells in the mammalian embryo depends on the POU transcription factor Oct4. Cell. 1998 Oct 30;95(3):379-91. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81769-9. PMID:9814708 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81769-9

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Palmieri SL, Peter W, Hess H, Scholer HR. Oct-4 transcription factor is differentially expressed in the mouse embryo during establishment of the first two extraembryonic cell lineages involved in implantation. Dev Biol. 1994 Nov;166(1):259-67. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1312. PMID:7958450 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/dbio.1994.1312

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Pesce M, Scholer HR. Oct-4: gatekeeper in the beginnings of mammalian development. Stem Cells. 2001;19(4):271-8. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.19-4-271. PMID:11463946 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1634/stemcells.19-4-271

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 Jerabek S, Merino F, Scholer HR, Cojocaru V. OCT4: dynamic DNA binding pioneers stem cell pluripotency. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014 Mar;1839(3):138-54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2013.10.001., Epub 2013 Oct 18. PMID:24145198 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagrm.2013.10.001

- ↑ Pan GJ, Chang ZY, Scholer HR, Pei D. Stem cell pluripotency and transcription factor Oct4. Cell Res. 2002 Dec;12(5-6):321-9. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290134. PMID:12528890 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.cr.7290134

- ↑ Kehler J, Tolkunova E, Koschorz B, Pesce M, Gentile L, Boiani M, Lomeli H, Nagy A, McLaughlin KJ, Scholer HR, Tomilin A. Oct4 is required for primordial germ cell survival. EMBO Rep. 2004 Nov;5(11):1078-83. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400279. PMID:15486564 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.embor.7400279

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Avilion AA, Nicolis SK, Pevny LH, Perez L, Vivian N, Lovell-Badge R. Multipotent cell lineages in early mouse development depend on SOX2 function. Genes Dev. 2003 Jan 1;17(1):126-40. doi: 10.1101/gad.224503. PMID:12514105 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.224503

- ↑ Wegner M, Stolt CC. From stem cells to neurons and glia: a Soxist's view of neural development. Trends Neurosci. 2005 Nov;28(11):583-8. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.08.008. Epub, 2005 Aug 31. PMID:16139372 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2005.08.008

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Masui S, Nakatake Y, Toyooka Y, Shimosato D, Yagi R, Takahashi K, Okochi H, Okuda A, Matoba R, Sharov AA, Ko MS, Niwa H. Pluripotency governed by Sox2 via regulation of Oct3/4 expression in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007 Jun;9(6):625-35. doi: 10.1038/ncb1589. Epub 2007 May 21. PMID:17515932 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncb1589

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Fong H, Hohenstein KA, Donovan PJ. Regulation of self-renewal and pluripotency by Sox2 in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008 Aug;26(8):1931-8. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1002. Epub 2008, Apr 3. PMID:18388306 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1634/stemcells.2007-1002

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 30.5 30.6 30.7 30.8 Michael AK, Grand RS, Isbel L, Cavadini S, Kozicka Z, Kempf G, Bunker RD, Schenk AD, Graff-Meyer A, Pathare GR, Weiss J, Matsumoto S, Burger L, Schubeler D, Thoma NH. Mechanisms of OCT4-SOX2 motif readout on nucleosomes. Science. 2020 Apr 23. pii: science.abb0074. doi: 10.1126/science.abb0074. PMID:32327602 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.abb0074

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 Soufi A, Garcia MF, Jaroszewicz A, Osman N, Pellegrini M, Zaret KS. Pioneer transcription factors target partial DNA motifs on nucleosomes to initiate reprogramming. Cell. 2015 Apr 23;161(3):555-568. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.017. Epub 2015 Apr , 16. PMID:25892221 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.017

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Zhang S, Cui W. Sox2, a key factor in the regulation of pluripotency and neural differentiation. World J Stem Cells. 2014 Jul 26;6(3):305-11. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v6.i3.305. PMID:25126380 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v6.i3.305

- ↑ Yamanaka S, Takahashi K. [Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse fibroblast cultures]. Tanpakushitsu Kakusan Koso. 2006 Dec;51(15):2346-51. PMID:17154061

- ↑ Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006 Aug 25;126(4):663-76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. Epub 2006 Aug, 10. PMID:16904174 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024

- ↑ Mahla RS. Stem Cells Applications in Regenerative Medicine and Disease Therapeutics. Int J Cell Biol. 2016;2016:6940283. doi: 10.1155/2016/6940283. Epub 2016 Jul 19. PMID:27516776 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2016/6940283

- ↑ McCabe MJ, Alatzoglou KS, Dattani MT. Septo-optic dysplasia and other midline defects: the role of transcription factors: HESX1 and beyond. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011 Feb;25(1):115-24. doi:, 10.1016/j.beem.2010.06.008. PMID:21396578 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.beem.2010.06.008

- ↑ Dong Z, Zeng Q, Luo H, Zou J, Cao C, Liang J, Wu D, Liu L. Increased expression of OCT4 is associated with low differentiation and tumor recurrence in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Pathol Res Pract. 2012 Sep 15;208(9):527-33. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2012.05.019. Epub, 2012 Jul 21. PMID:22824146 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.prp.2012.05.019

- ↑ Hassiotou F, Hepworth AR, Beltran AS, Mathews MM, Stuebe AM, Hartmann PE, Filgueira L, Blancafort P. Expression of the Pluripotency Transcription Factor OCT4 in the Normal and Aberrant Mammary Gland. Front Oncol. 2013 Apr 11;3:79. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00079. eCollection 2013. PMID:23596564 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2013.00079

- ↑ Wen J, Park JY, Park KH, Chung HW, Bang S, Park SW, Song SY. Oct4 and Nanog expression is associated with early stages of pancreatic carcinogenesis. Pancreas. 2010 Jul;39(5):622-6. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181c75f5e. PMID:20173672 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181c75f5e

- ↑ Rodini CO, Suzuki DE, Saba-Silva N, Cappellano A, de Souza JE, Cavalheiro S, Toledo SR, Okamoto OK. Expression analysis of stem cell-related genes reveal OCT4 as a predictor of poor clinical outcome in medulloblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2012 Jan;106(1):71-9. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0647-9. Epub 2011 Jul, 2. PMID:21725800 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11060-011-0647-9

|