User:David L. Nelson/Sandbox 9

From Proteopedia

Contents |

Insulin

Introduction

Insulin is an extremely important hormone in the human body, and has a role in many physiological processes, most notably maintaining blood glucose levels. When the body has difficulties producing or recognizing insulin, a person may develop diabetes. Diabetes is one of the most recognized epidemics that affects the United States, and effects nearly 24 million Americans.[1] Knowing the structure of insulin lends us insight into its function and how that relates to diabetes.

We chose insulin for our research because we are both aspiring secondary teachers. More than 13,000 young people are diagnosed with type 1 diabetes every year, and a majority of these cases are related to obesity. Today’s youth is physically inactive, and not aware of the health consequences that await them. We feel that as educators, we need to do a better job educating our students on the health risks that are associated with a video game and TV driven lifestyle. Our hope is that as more and more young people are aware of these consequences, the numbers of people diagnosed with diabetes will go down.

Structure

|

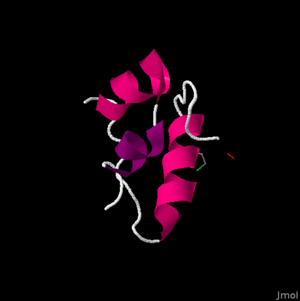

The primary structure of the insulin protein is relatively simple, consisting of only two chains of amino acids. The two chains, the and the have 21 and 30 amino acids respectively. The A-Chain has a free amine group on the N-terminal and a free carboxylic acid on the C-terminal, both of which become important in the binding of the protein. The amino acids are termed residues, which refers to the loss of a hydrogen atom from the peptide bonding in order to form the polymer.

The secondary structure is fairly compact. At this level, we begin to see the . The A-chain contains two sections of alpha helixes in the A-chain between Isoleucine (A2) and Threonine (A8) as well as Leucine (A13) and Tyrosine (A19).[2] These two sections are important, in that they allow they are able to lie alongside each other in Van der Waals contact. These residues are highly conserved evolutionarily, and are vital in the structure and function of the insulin hormone.

A Van der Waals force is different than a covalent and ionic bond, and can be important in structural biology in that it helps to define the solubility of organic compounds. The B-chain also contains an alpha helix, which is larger than those in the A-chain. The alpha helix in the B-chain runs from B9 to B19. It also folds into somewhat of a ‘U’ shape by the glycine residues at B20 and B23. This shape allows the C-terminal residues, Phenylalanine (B24) and Tyrosine (B26), to also be in Van der Waals contact with the alpha helix. This becomes important in the binding of the insulin protein to the insulin receptor. The B-chain’s highly conserved, and thus crucial region ranges from B8-25.

The tertiary structure contains that, along with the Van der Waal’s forces, stabilize the molecule. This disulfide bonds are highlighted in red. The disulfide bonds are formed between cysteines. There are , highlighted in blue, with four in the A-chain (A6,A7,A11,A20), and 2 in the B-chain (B7,B19). More specifically these bonds are formed between A6 and A11, A7 and B7, and A20 and B19. These become very important in receptor binding for insulin.

These cysteine residues promote a parallel arrangement between A7-20 and B7-19, and more specifically the A6-A11 disulfide bond brings the C-terminal TyrA19 and the N-terminal GlyA1, IleA2, ValA3 closer together. Three mutations have been found to be key in the development of diabetes in humans. B-chain mutations of PheB24 changed to SerB24, PheB25 to LeuB25, and an A-chain mutation of ValA3 changed to LeuA3 are all correlated with impaired biological activity. Overall, this molecule has a non-polar interior and a polar exterior, mainly due to the make-up of the B-chain. Insulin’s quaternary structure is a hexamer formation of six insulin molecules in a life preserver shape. The only difference between human and porcine insulin occurs at . In human insulin, this amino acid is a threonine, highlighted in purple at the right, whereas in porcine insulin this amino acid is an alanine.

Function

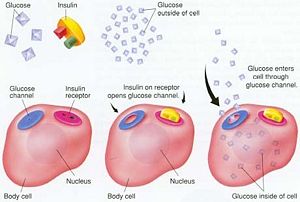

The major function of insulin is to counter the action of a number of blood sugar generating hormones and to maintain low glucose levels. Because there are numerous high blood sugar hormones, disorders associated with insulin usually lead to severe high blood sugar and other complications. In addition to its role in regulating glucose metabolism, insulin brings about the creating of fat cells, decreases the breakdown of lipids, and increases amino acid transport into cells. Insulin also regulates transcription and stimulates growth, DNA synthesis, and cell replication.

Insulin is synthesized in the β-cells of the islets of Langerhans. Its signal peptide is folded to its basic structure and locked in this conformation by the formation of 2 disulfide bonds. Insulin secretion from β-cells is principally regulated by glucose levels. Increased uptake of glucose by pancreatic β-cells leads to a complementary increase in metabolism. The increase in metabolism leads to the inhibition of an ATP-sensitive potassium channel (KATP channel). The net result is insulin secretion. This role of KATP channels in insulin secretion presents a target for treating high blood sugar due to insulin insufficiency as is typical in type 2 diabetes.

When glucose enters the cells it is used in the respiratory cycle and glycolysis. During this process many high-energy ATP molecules are produced by oxidation, raising the ATP:ADP ratio. This ratio triggers the closing of potassium channels as the cell membrane depolarizes, which then opens calcium channels allowing extracellular calcium to flow into the cell. It is this concentration change that then triggers the release of synthesized insulin. There are many other factors that trigger the release of the insulin hormone from the pancreas, but this is the most common.

Insulin is crucial in maintaining blood glucose levels and the homeostasis of the body that stems from this value. Insulin drives the storage of glucose in the liver and muscle tissue in the form of glycogen, which is also the clinical use of insulin in reducing high blood glucose levels that can branch from diabetes. Insulin also helps to control fatty acid synthesis, proteolysis, gluconeogenesis, esterification, lipolysis, and arterial muscle tone, making it a vital hormone in the overall workings of the body and general health.[3]

Role in Diabetes

Diabetes is a disease associated with insulin that is sweeping our nation and world right now. All types of diabetes have something to do with a shortage of insulin or a decreased ability to use it. Since insulin is crucial in maintaining blood glucose levels and the homeostasis of the body that stems from this value, these shortages lead to improper regulation of glucose levels in the blood stream. This can lead to many difficulties with regular organ functions throughout the body.[4] When people have diabetes, clinical insulin is injected into patients to reduce high blood glucose levels.

Oftentimes these injections use human insulin that is manufactured semi-synthetically or with recombinant DNA. Sometimes, however, the insulin used in these injections is not human insulin, but insulin derived from the pancreases of cows or pigs. As discussed earlier, the only difference between the porcine insulin and human insulin is one amino acid. This difference, however, can have major effects on patients. Examples of these effects include allergic reactions resulting in hives from the porcine insulin.[5]

Type I and II diabetes are the most talked about in the U.S. Type I diabetes consists of an autoimmune response against the bodies insulin, depleting the bodies supply. The exact cause of this disease is not known. Other possible factors encompass a combination of autoimmune, environmental factors, and genetics. Type II diabetes is an onset disease in which the body stops responding to its insulin because of an increased tolerance. This is linked closely linked with obesity, and is most closely associated with the diabetes epidemic in the U.S.

References

- ↑ Stumvoll, M., Goldstein B.J., Van Haeften, T.W. Type 2 diabetes: principles of pathogenesis and therapy. 2005. The Lancet Volume 365, Issue 9567, P. 1333-1346.

- ↑ Brange J. & Langkjoer L. Insulin structure and stability. 1993. Pharm. Biotechnol. 315–355.

- ↑ Bell DS. Exercise for patients with diabetes. Benefits, risks, precautions. 1992 July; 92(1): 183-4, 187-90, 195-8. Available from: Postgraduate Medical Journal.

- ↑ Hayes, Charolette, Kriska Andrea. Diabetes management and prevention. PubMed [1]. 2008 April; S19-23. Available from: Journal of the American Dietetic Association.

- ↑ Mann, N.P., Johnston, D.I., Reeves, W.G., Murphy, M.A. Human insulin and porcine insulin in the treatment of diabetic children: comparison of metabolic control and insulin antibody production. 1983. British Medical Journal Volume 287 P.1580-1582.