Background

Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase (ALK) is a transmembrane receptor and a member of the family of Receptor Tyrosine Kinases (RTKs)[1]. RTKs are a family of biomolecules that are primarily responsible for biosignaling pathways such as the insulin signaling pathway.[2] ALK was identified as a novel tyrosine phosphoprotein in 1994 in an analysis of Anaplastic Large-Cell Lymphoma, the protein's namesake.[2] A full analysis and characterization of ALK was completed in 1997, properly identifying it as an RTK, and linking it closely to Leukocyte Tyrosine Kinase (LTK).[2] ALK's normal activity as a receptor tyrosine kinase is to transfer a gamma-phosphate group from adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to a tyrosine residue on its substrate.[2] ALK is one of more than 50 RTKs encoded within the human genome, [2] and its tyrosine kinase activity seems to be especially important in the developing nervous system. [2] The ALK extracellular domain is becoming well characterized, as it is the primary binding site of ALK ligands that end up triggering the kinase activity, as ALK autophosphorylates itself.[3] There are four well-characterized domains on the ALK extracellular domain that are involved in binding the two main ligands of ALK.[3] ALK is most commonly associated with oncogenesis, as various factors, including overstimulation, lead to extreme cell proliferation.[4] It is primarily found in the fetal and infant developing nervous system, however when associated with cancer it can be found in systems other than the nervous system.[5] Examples of these include colon and prostate cancer, where ALK is not normally expressed.[6] This particular protein is interesting in part due to its unique structure, of that it shares the most similarity with LTKs and its association with devastating cancers.[7]

Structure

ALK is a close homolog of LTK, and together these two homologs constitute a subgroup within the superfamily of

insulin receptors[4]. ALK is composed of three primary regions: the extracellular region, the transmembrane region, and the intracellular region.

[3]

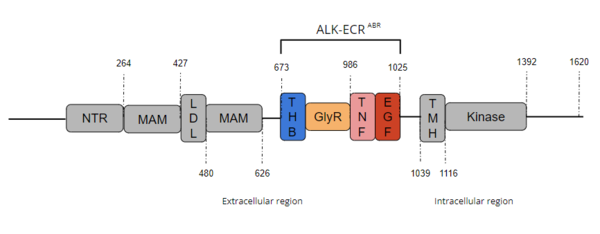

Figure 1. Overview of Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase Structure with domains where known structures are color coordinated and other domains are grayed out. The abbreviations are as follows: NTR-N-terminal Region, MAM-Meprin-A-5 protein-receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase μ, LDL-low-density lipoprotein receptor class A, THB-three helix bundle-like, GlyR-poly-glycine region, TNF-tumor necrosis factor-like domain, EGF-epidermal growth factor-like, TMH-transmembrane helix

The extracellular region of ALK contains 8 total domains within 2 fragments.

[3] A Three Helix Bundle-like domain (THB-like), a Poly-Glycine domain (GlyR), a Tumor Necrosis Factor-like domain (TNF-like), and an Epidermal Growth Factor-like domain (EGF-like) make up the ligand binding fragment while an N-terminal domain, two

meprin–A-5 protein–receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase μ (MAM) domains and a

low-density lipoprotein receptor class A (LDL) domain sandwiched between the two MAM domains make up the second fragment.

[3] All four domains of the ligand binding fragment of the extracellular region contribute to ligand-binding

[2]. The presence of an LDL domain sandwiched by two MAM domains is a unique feature that ALK does not share with other RTKs. The purpose behind this unique difference is still unclear, but the MAM region has been hypothesized to play a role in cell-cell signaling

[8]. The

transmembrane helical region (TMH) bridges the gap between the intracellular and extracellular regions.

[3] The intracellular tyrosine kinase region features the Kinase domain and the C-terminal end (Figure 1).

[3]

Known Extracellular Domains

Three Helix Bundle-like Domain

The performs a structural function by interacting with the TNF-like domain upon ligand binding.[3] The THB-like domain's α-helix interacts with the helix α-1' and β strand A-1' on the TNF-like domain.[3] This outermost region of the extracellular ligand-binding domain undergoes substantial structural reorientation upon ligand binding.[3] The THB-like is primarily involved in the of ALK and interacts with the TNF-like domain, which causes dimerization of ALK. [3]

To return to Structure of ALK with ALKAL2 bound scene click here:

Poly-Glycine Domain

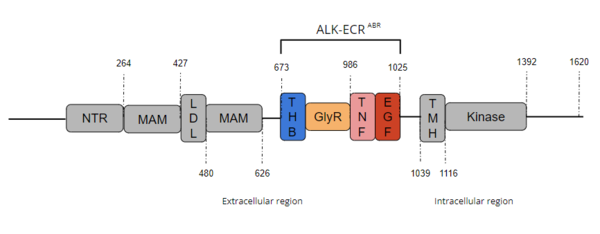

Figure 2. Rare Glycine helices on Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase; The structure of extracellular ALK is shown in a perpendicular, cross-sectional way, highlighted in orange. In black, hydrogen bonds are structured in a hexagonal-like way. Made using

7N00Located between the THB-like domain and the TNF-like domain, the has an important structural role.

[3] The GlyR domain also has a rare and unique structure of left-handed glycine helices with hexagonal hydrogen bonding (Figure 2).

[3] These 14 glycine helices are unique to ALK's function among other tyrosine kinases.

[3] These helices are rigid structures, providing a strong anchor for the ligand binding site while the other domains undergo conformational rearrangements.

[3]

To return to Structure of ALK with ALKAL2 bound scene click here:

Tumor-Necrosis Factor-like Domain

The interacts with the THB-like domain to begin the conformational changes associated with ligand binding.[3] Located in approximately the mid-region of the extracellular region, the TNF-like domain bridges the gap between the GlyR domain and the EGF-like domain. The TNF-like domain also assists in mediating ligand binding with the EGF-like domain[3] by interacting with the THB-like domain to facilitate the critical conformation changes required for dimerization and ligand recognition.[3]

To return to Structure of ALK with ALKAL2 bound scene click here:

Epidermal Growth Factor-like Domain

Unlike the poly-Glycine helices, the is malleable and repositioning of this domain is essential for activation of the protein.[3] This domain undergoes conformational changes upon ligand binding and when in contact with the TNF-like domain.[3] The consists of primarily hydrophobic residues, which enables their flexibility with regards to one another.[3] The EGF-like domain is essential in binding, and thus this ability of the EGF-like to be very malleable in its interactions with the TNF-like domain is important. [3] Without these interactions, ligand binding does not occur. [3] Hydrogen bonding occurs mostly between residues on the TNF-like domain.[3] There is only one hydrogen bond between the domains that are between residues Y734 on the TNF-like interface and Y984 on the EGF-interface.[3] Major motifs in the EGF-like domain are major and minor β-hairpins, which are stabilized by 3 conserved disulfide bridges. [3] The major β-hairpins in the EGF-like domain interact with the ALKAL2 helices after ALKAL2 binding [3].

To return to Structure of ALK with ALKAL2 bound scene click here:

Extracellular Domain Binding

Ligands

The extracellular ligands of ALK are Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase Ligand 2 (ALKAL 2) and Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase Ligand 1 (ALKAL 1) which are polypeptides of 76 and 70 lengths respectively.

ALKAL2

is a shared ligand of ALK and LTK. Dimeric ALKAL2 and monomeric ALKAL2-AD both induce dimerization of ALK [3]. Structurally, ALKAL2 has an N-terminal variable region, a conserved augmentor domain, and tends to aggregate in the cell [3]. ALKAL2, as it binds as a dimer, contains a higher potency of binding to the ALK receptor than the other primary ligand, ALKAL1.[9] Overexpression of ALKAL2 is linked to high-risk neuroblastoma in absence of an ALK mutation [10].

To return to Structure of ALK with ALKAL2 bound scene click here:

ALKAL1

is a monomeric ligand of ALK. Structurally, ALKAL1 shares the same architecture as ALKAL2 with an N-terminal variable region and a conserved C-terminal augmentor domain [3]. However, in ALKAL1, the N-terminal variable region is shorter and has limited sequence similarity to ALKAL2. Overall, ALKAL1 still shares 91% sequence similarity with ALKAL2. Both ligands include a three helix bundle domain in their structures, with an extended positively charged surface for ligand binding to the TNF-like domain[3]. ALKAL1 as a monomer, however, binds to ALK with poor stability[6] and was only found to stimulate ALK dimerization at much higher concentrations than ALKAL2.[9]

To return to Structure of ALK with ALKAL2 bound scene click here:

Binding Site

The binding site is located in the TNF-like region. [7] This site doesn't start out surrounding the ligand, instead the ligand binding initiates conformational changes across the extracellular region of the protein. The ligands for ALK have highly positively charged faces that interact with the TNF-like region, the primary ligand-binding site on the extracellular region[11]. Salt bridges between the positively charged residues on the ligand and negatively charged residues on the receptor are stabilized by ligand binding. Three of these occur between , , and . These strong ionic interactions also induce the conformational changes in the extracellular domain that induce the signaling pathway which include an 80-degree bending of the TNF-like and GlyR domains toward the membrane with the link acting as a hinge and a 160-degree rotation across the z-axis across the TNF-like and GlyR domains. [3]

To return to Structure of ALK with ALKAL2 bound scene click here:

Dimerization of ALK

After binding to one of its ligands, ALK undergoes [2]. is mediated mostly by weak Van der Waals interactions and main chain hydrogen bonding between the TNF-like domain on one monomer and the THB-like domain on the other. [3] The dimerization causes trans-phosphorylation of specific tyrosine residues located in the extracellular region in the activation loop which in turn transmits a signal downstream[2]. It has been presumed that the phosphorylation cascade activates ALK kinase activity [2].

Function

ALK plays a role in cellular communication and in the normal development and function of the nervous system[2]. ALK is present in the developing nervous system of a fetus and newborn. ALK expression dwindles with age.[2] In addition to being heavily expressed in the brain, ALK is present in the small intestine, testis, prostate, and colon [4].

Disease and Medical Relevance

Cancer

In ALK fusion proteins, the ALK fusion partner may cause dimerization independent of ligand binding, leading to oncogenic ALK activation [2].

Approximately 70-80% of all patients who have Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (ALCL) contain the genetic complex of the ALK gene and the nucleolar phosphoprotein B23. This complex is also called the numatrin (NPM) gene translocation and creates the NPM-ALK complex. This chimeric protein is expressed from the NPM promoter, leading to the overexpression of the ALK catalytic domain. This overexpression of ALK is characteristic of most cancers that are linked to tyrosine kinases, as the overexpression of these proteins leads to uncontrollable growth [4].

Pediatric Neuroblastoma

Mutations in ALK can produce oncogenic activity and are a leading factor in the development of some pediatric neuroblastoma cases[10]. 8-10% of primary neuroblastoma patients are ALK positive[10] suggesting that ALK overstimulation is a primary factor in propagating the growth of neuroblastoma. This overstimulation of ALK works in concert with the neural MYC oncogene and uses the ALKAL2 ligand. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors are proposed to inhibit the growth of further neuroblastoma cells, creating a potential pathway of treatment[10].

Inhibition and Regulation

The regulation of ALK dimerization by ALKAL points to one clear way of inhibiting ALK activity and may offer new therapeutic strategies in multiple disease settings [11]. As the dimerization of ALK is essential for the activation of this protein, the inhibition of this activation is a potent way of inhibiting further ALK activity.[11] The inhibition and regulation of this extracellular region of ALK are actively being explored, as this part of ALK is part of what distinguishes it from other RTKs, like LTK. Researchers are currently exploring the use of antibodies and more specifically monoclonal antibodies[5] as a means of inhibiting the activity of ALK through the extracellular domain. It is hypothesized that these monoclonal antibodies act by binding to the binding site of ALK, thus preventing ALKAL from binding[11], and inducing cytotoxicity to the cancerous cell itself.[5]

In colorectal cancer specifically, it has been found that gene silencing for ALKAL1 is a method of stopping tumorigenesis as in those cell lines there was an upregulation of ALKAL1, stimulating the overexpression of the ALK gene.[6] This gene silencing method was shown to stop the Sonic Hedgehog signaling pathway, which is important in initial neural development and is an important signaling pathway in some cancerous cell lines when misregulated.[6] These methods of ALK dimerization inhibition show extensive promise in the field of cancer research, and demonstrate ways that ligand binding can be inhibited.