Sandbox Reserved 768

From Proteopedia

| This Sandbox is Reserved from Sep 25, 2013, through Mar 31, 2014 for use in the course "BCH455/555 Proteins and Molecular Mechanisms" taught by Michael B. Goshe at the North Carolina State University. This reservation includes Sandbox Reserved 299, Sandbox Reserved 300 and Sandbox Reserved 760 through Sandbox Reserved 779. |

To get started:

More help: Help:Editing |

Contents |

Phenylalanine Hydroxylase

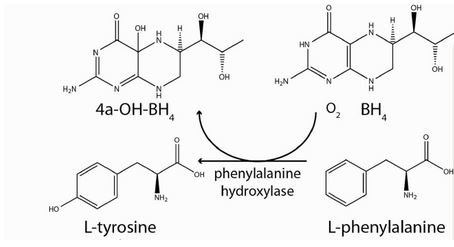

Phenylalanine Hydroxylase (also known as Phenylalanine-4-monooxygenase or simply PAH) is the enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of L-phenylalanine into L-tyrosine by hydroxylation (addition of an -OH group) of the aromatic side chain of phenyalanine. This reaction is the initial and rate-limiting step in the phenylalanine catabolism pathway.

|

PAH uses tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) as a cofactor and has a nonheme iron atom bound to its active site. PAH is classified as an oxidoreductase, specifically enzyme class EC 1.14 since its mechanism of action involves the oxidation/reduction of its substrate. [2].

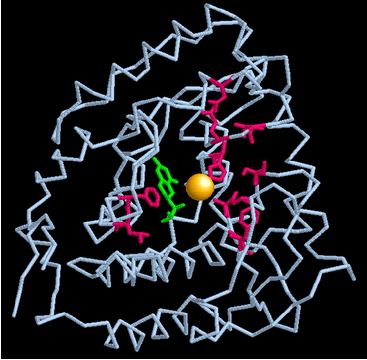

PAH enzyme is present in the liver cells of humans and other mammals. It is also present in non-mammalian eukaryote organisms and some bacteria such as E.coli. [2]. Recently, it has been identified in some protozoans and slime molds, and even in nonflowering plants such as spinach from which it has been extracted and studied. [3]. Mammalian PAH is a homo-tetrameric enzyme of 50 kDa subunits composed of two asymmetric dimeric units. The four subunits are connected to each other via a coiled-coil motif as shown in the diagram below.

Each monomeric subunit is composed of three sites: the N-terminal, the catalytic site, and the C-terminal. [1].

PAH enzyme has been studied extensively because of its correlation with the genetic defective condition phenylketonuria (PKU). Errors in the function or stability of PAH lead to its malfunction which causes a buildup of phenylalanine resulting in numerous health detriments.

Phenylalanine Hydroxylase Mechanism of Action

PAH, belonging to the oxidoreductase enzyme class, acts by oxidizing/reducing its substrate. Specifically, PAH acts on paired donors with pteridine being a donor and first incorporates one atom of molecular oxygen into the aromatic ring of phenylalanine. [2]. Then, it reduces the second oxygen atom to water using the two electrons that are supplied by the BH4 cofactor. BH4 is also hydroxylated at each turnover to produce pterin-4a-carbinolamine (4a-OH-BH4), with consequent dissociation from the enzyme. 4a-OHBH4 is dehydrated and reduced back to BH4 by the action of the enzyme pterin carbinolamine dehydratase. [1].

Kinetics Overview

Formation of the productive PAH−BH4−phenylalanine complex begins with the rapid binding of BH4 (Kd = 65 μM). Subsequently, phenylalanine is added to the binary complex to form the productive ternary complex (Kd = 130 μM). This second step is approximately 10-fold slower. Both substrates are able to bind to the free enzyme form to produce inhibitory binary complexes. Molecular oxygen rapidly binds to the formed productive ternary complex; which is then followed by formation of an unidentified intermediate. This intermediate can be detected as a decrease in absorbance at 340 nm, with a rate constant of 140 s−1. Formation of the 4a-OHBH4 and Fe(IV)O intermediates is 10-fold slower and is followed by the rapid hydroxylation of the amino acid. Product release is the rate-determining step and largely determines kcat. [4].

Phenylalanine Hydroxylase Structure

|

Although the full-length structure of mammalian PAH has not yet been clearly known, a large part of it has been identified. [1]. It was solved by means of crystallizing the protein (at pH=7) to perform X-ray diffraction using molecular replacement. The search model used was based on the crystal structure of tyrosine hydroxylase because of the similarity between the two enzymes. [5]. The R-factor recorded was 0.251 and the mean B (or temperature) value was 33.0. [2].

Structure Revealed

The monomeric unit of PAH is composed of three sites: an N-terminal regulatory domain (residues 1–110), a core catalytic domain (residues 111–410), and a C-terminal oligomerization or tetramerization domain (residues 411–452). [1].

The N-terminal regulatory domain is a regulatory module present in several proteins, which functions in the dimerization and binding of amino acids. It is flexibly attached to the catalytic domain via a hinge region (Arg111–Thr117). [1].

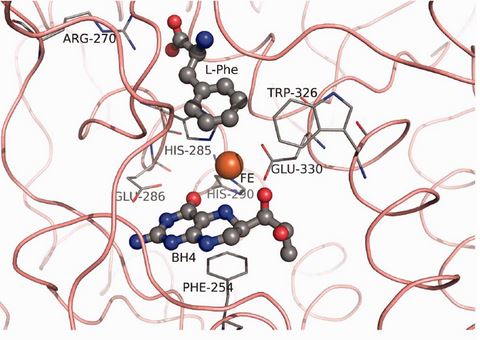

The catalytic domain contains the active site of the enzyme. It is composed of 13 α-helices and 8 β-strands [5] and houses the binding sites for the nonheme iron atom, the cofactor, and substrate. The iron binds to two histidines (His285 and His290 in hPAH) and a glutamate (Glu330) in the deep cleft in the core of each monomer. [1].

The C-terminal oligomerization or tetramerization domain begins with an antiparallel-sheet (residues 411–414, 421–424) and is formed by a C-terminal “arm” consisting of two β-strands, forming a β-ribbon, and a 40 Å long α-helix. This C-terminal arm extends over an adjacent monomer, thus bringing the four helices (one from each monomer) into a closely packed anti-parallel coiled-coil motif in the center of the structure (as can be seen in the tetramer structure above). [5]. The assembly of the enzyme occurs through a swapping mechanism in which the secondary structural elements mutually switch their position to promote oligomerization. [5].

The residues surrounding the iron atom in the active site are: PHE 254, ARG 270, HIS 285, GLU 286, TRP 326, and GLU 330. [1]. The illustration below highlights these residues and their relative positions to the iron atom, BH4 cofactor, and the L-Phenyalanine substrate.

PAH Mutations

Mutations and changes in the β-ribbon region have major detrimental effects on the enzyme stability. The mutations that lead to Phenylketonuria are most likely due to mutations in the PAH gene that cause changes at the junction between the catalytic and tetramerization domains of the enzyme. [5]. This leads to loss of enzyme stability and extensive misfolding which subsequently results in enzyme malfunction. [1]. The monomeric image below highlights the regions in the active site that, if mutated, would destroy enzyme activity and lead to phenylketonuria. The yellow atom is iron, the green structure is the BH4 cofactor, and the red sites are a few examples of mutation regions.

Phenylketonuria

Overview

Phenylketonuria (PKU) is the most common inborn error of amino acid metabolism. [6]. It is genetic autosomal recessive disorder and a relatively common condition affecting approximately 1 in 10,000 newborn infants in the USA and Europe. [6]. The Phenylhydroxylase enzyme gene consists of 13 exons and introns and when both alleles are mutated (resulting in the mutated regions highlighted in the enzyme active site illustration above), phenylketonuria arises.[7]. The two mutations may occur in any of the exons, intervening introns, or perhaps in other regions such as the promoter.

Loss of PAH activity results in increased concentrations of phenylalanine in the blood and toxics in the brain. In addition, dysfunctional PAH leads to the appearance, in urine, of metabolites that arise from the transamination of L-Phe to phenylpyruvate. [1]. Phenylketonuria is classified by the severity of hyperphenylalaninaemia.[7]. The normal range of blood phenylalanine concentrations is 50–110 μmol/L. Individuals with blood phenylalanine concentrations of 120–600 μmol/L are classified as having mild hyperphenylalaninaemia; those with concentrations of 600–1200 μmol/L are classified as mild phenylketonuria; and concentrations above 1200 μmol/L denote classic phenylketonuria. [7].

Symptoms

The common signs and symptoms associated with phenylketonuria include: progressive intellectual impairment, depression, and purposeless movement. [1]. Other symptoms that have been noted encompass eczematous rash, autism, seizures, and motor deficits. [7]. However, the classic symptoms are those of neurophysiological and psychiatric impairments.

Molecular Explanation

The correlation between PAH malfunction and neurological deterioration can be explained as follows. The accumulation of phenylalanine inhibits the function of the aminoacid transporter 1 (LAT 1) at the brain's entry. [7]. This is detrimental because such transporter mediates the entry of other amino acids such as tyrosine and tryptophan into the brain. [7]. Once this transporter carrier is impaired, such amino acids are unable to cross into the brain. These aromatic amino acids serve as precursors to the synthesis of important neurotransmittors- tyrosine is a precursor for dopamine and norephinephrine, and tryptophan is a precursor for serotonin. Their absence then immensely disrupts the production of important neurotransmitters, hence resulting in the neurological impairment seen with phenylketonuria.

Treatment

There does not seem to be any medicinal treatment available to alleviate the symptoms of phenylketonuria. The most important step in managing this condition is dietary phenylalanine monitoring and restriction and this usually begins immediately after confirmation of hyperphenylalaninaemia in a neonate. [7]. Patients with phenylketonuria have to accept the phenylalanine-free formula and avoid foods rich in protein as well as foods and drinks containing aspartame, flour, and soya. Low-protein natural foods such as potatoes, some vegetables, and most cereals can be eaten but only in severely restricted amounts. Luckily, low-protein variants of some foods exist, such as low-protein bread and low-protein pasta. [7]. Diet monitoring and management has been shown to very successful in controlling phenylketonuria and halting its progression.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 Flydal, Marte, and Aurora Martinez. "Phenylalanine Hydroxylase: Function, Structure, and Regulation." International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Journal 65.4 (2013): 341-349. Web.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=1J8U

- ↑ Nair, P, and L Vining. "Phenylalanine Hydroxylase from Spinach Leaves." Phytochemistry 4.3 (1965): 401-411. Web.

- ↑ Roberts, Kenneth, Jorge Pavon, and Paul Fitzpatrich. "Kinetic Mechanism of Phenylalanine Hydroxylase: Intrinsic Binding and Rate Constants from Single-Turnover Experiments." Biochemistry 52(2013): 1062-1073. Web.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Fusetti, Fabrizia, Heidi Erlandsen, Torgeir Flatmark, and Raymond Stevens. "Structure of Tetrameric Human Phenylalanine Hydroxylase and Its Implications for Phenylketonuria." The Journal of Biological Chemistry 273.27 (1998): 16962-16967. Web.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Lendley, Fred, Anthony DeLilla, and Savio Woo. "Molecular Biology of Phenylalanine Hydroxylase and Phenylketonuria." Trends in Genetics 1(1985): 309-313. Web.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Blau, Nenad, Francjan Van Spronsen, and Harvey Levy. "Phenylkentonuria." The Lancet 376.9750 (2010): 1417-1427. Web.