Background Information

Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I (abbreviated for obvious reasons as MHC Class I) is a key component of your immune system. The protein is a glycoprotein (protein with a sugar attached) present on all cells in your body. Its function is to show peptides (short stretches of 9-10 amino acids), both self and foreign, to the immune system. This presentation helps the immune system determine whether the body has been infected by a foreign agent (bacteria or virus). When the body is not infected with a pathogen, peptides derived from normal proteins present in your cells are presented on the Class I MHC molecule (these peptides are known as “self” peptides). These peptide-MHC combinations are ignored by the immune system, as the cells of the immune system (mainly T-cells) have been “trained” to not react to self peptides present on the MHC. However, when the body is infected with a pathogen like a virus, cells are commandeered by the virus to produce large amounts of viral proteins that will be used to make new virus. Some of these proteins are broken down by the cell into peptides, and presented on the Class I MHC molecule (these are known as “foreign” peptides). T-cells, the cells that recognize MHC Class I complexed with peptide, are trained to recognize only those MHC Class I molecules that are presenting foreign peptides--such as these protein pieces from the viral invader. The MHC Class I + foreign peptide complex is recognized differently and is key to developing an effective immune response against the pathogenic invader.

As a safety device, the T cell receptor (TCR) on the cytotoxic T cells will only recognize the MHC Class I molecule after it has a foreign peptide bound to it. Since the MHC Class I complexed with self peptides does not trigger an immune response, this keeps the immune system from constantly attacking normal cells, and yet allows the immune system to react quickly to the presence of foreign invading organisms. Autoimmune diseases (such as rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes) often involve the inappropriate recognition of MHC moleules bound to self-peptides, leading to the immune system attacking normal tissue.

You will also encounter MHC molecules if you choose to have yourself tissue typed as a bone marrow or organ donor. There are many different types of MHC molecules - different alleles for the gene; in your body you only use 6 different types and this helps to establish your unique molecular identity - the combination of your six types will certainly be different from your lab mate, but perhaps the same as a family member - remember the joy of genetics.

From a structural point of view, MHC molecules are also cool because you can clearly see alpha helices, beta-pleated sheets, ionic bonds, and quaternary structure. An apt description of the MHC-peptide complex is that it looks like a hot dog (peptide) in a bun (MHC). One other interesting note: the MHC complexes are closely related to immunoglobulins, both being made up of the same basic protein domain motifs (along with the T-cell receptor and several other important immune molecules). These genes all belong to a “superfamily” of related genes, the Ig superfamily.

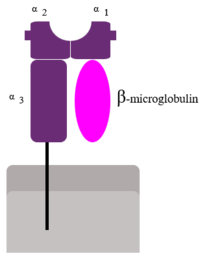

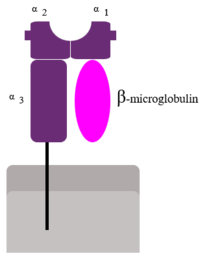

Two subunits of MHC I (alpha--contains alpha 1, 2 and 3 domains--and Beta-microglobulin)

Interaction of MHC Class 1-Antigen complex with TCR

Structure

1. What color is used for the alpha helices?

2. What color is used for the beta sheet?

3. Which subunit(s) (in the 3D model) is/are the MHC molecule? Which subunit(s) is/are the peptide? Think of the hot dog and bun analogy...

4. Which subunit(s) of the MHC molecule play a direct role in binding of the peptide?

- 5. The fit of the peptide in the MHC molecule requires some precision and the peptide must be within a narrow range or lengths. Why do you think this might be (think about the consequences if just any old peptide (of any length) could fit into the MHC groove)?

Hmm...but just how tight does the fit of the peptide look in the MHC groove? Now, open the . Here you are seeing only subunits D and F from the previous image.

6. What is different - or - where did all the space go? To get a feel for this new view and how it relates to the previous model, click on the "popup" button on the bottom right of the structure box. A new window with the MHC 3D structure will open. Then, right click on the 3D image (or ctrl-click for Mac users), then:

a. "Select"-->"all"

b. "Style"-->"structures"-->"backbone"

Now this looks a lot more like the previous MHC model image from parts 1-5.

Click here to reload original:

Surprisingly, the fit of the peptide is not incredibly tight, and many different peptides will fit into any given MHC molecule.

- 7. If you were to alter amino acids in the MHC molecule to (a) affect binding to the peptide, which would you alter? Keep in mind that amino acids within the alpha helices and beta sheets that have side chains that project towards the bound peptide play a crucial role in peptide binding. (b) affect binding to the T cell receptor molecule, which would you alter? (Remember that the T-cell receptor recognizes the whole peptide/binding cleft region as a whole, including amino acids that don’t actually contact the peptide). List 2 amino acids for each answer. (To answer this, move your cursor over an amino acid side chain (light blue) on the image in the area where you would alter something and let the program identify the amino acid for you (three letter code followed by a number at the beginning of the ID string that pops-up).

The following two questions can be answered without the computer. You may want to skip them for now and keep working. Just make sure that you come back to them later!

- 8. What might be the role of the portion of the MHC not involved in direct binding to the peptide? Use your imagination, look at pictures in your book (Chapter 43), or look up and read about MHC on the web (wikipedia would work) and list as many as you can - don’t worry about the true answer, yet!

- 9. A very similar molecule in your immune system is called MHC Class II. (See diagrams in Campbell, Chapter 43 or on wikipedia.) This molecule is structurally and functionally analogous to an MHC Class I molecule. Juvenile diabetes is a disease caused (at least in part) when your MHC Class II molecules erroneously present a peptide from your pancreas. This targets the cells of your pancreas for destruction by your immune system and hence the disease -- called an "autoimmune disease" because you are “immune” to yourself. Interestingly, the cause is a mutation in the genes that code for the MHC molecule. From what you have learned so far, it would be reasonable to assume that the mutation has affected the binding of the MHC to the pancreatic peptide. BUT, while this is in part true, the mutation also disrupts a “salt-bridge” (a weak ionic bond) between the two alpha helices. (An example would be a bridge between Asp77 and His151 in the MHC Class I protein). How could this affect peptide binding? Think back to what you know about how a protein shape is determined.