This old version of Proteopedia is provided for student assignments while the new version is undergoing repairs. Content and edits done in this old version of Proteopedia after March 1, 2026 will eventually be lost when it is retired in about June of 2026.

Apply for new accounts at the new Proteopedia. Your logins will work in both the old and new versions.

User:Wade Cook/Sandbox 1

From Proteopedia

Smallpox (Variola Virus) - Topoisomerase 1B

Smallpox is an acute, highly contagious disease, which causes disfiguring and febrile rash-like illness, which has no known cure. According to some health experts, smallpox was responsible for more deaths than all other infectious diseases combined thus far in the world's history [1]. The disease causes high morbidity and mortality and led to the deaths of approximately 500 million people in the 20th century alone. With so many people affected, in an intensive public health vaccination campaign was initiated by the World Health Organization (WHO) to eradicate smallpox as a human disease in the 1960’s. There were two forms of the disease worldwide: Variola major, the deadly disease, and Variola minor, a much milder form [2]. Although naturally occurring smallpox no longer exists, there are concerns that the variola virus could be used as an agent of bioterrorism or biowarfare. As a result, it is critical to understand the molecular dynamics and virulence factors in order to prepare for a potential epidemic and to prevent the devastating consequences [2].

| |||||||||||

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Smith, K. “Smallpox. can we still learn from the journey to eradication?” Indian Journal Of Medicine. 137.5 (2013): 895-899.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 “Smallpox.” Center for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC, n.d. Web. 28 Oct. 2015. <http://www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/smallpox/index.asp>

- ↑ Shubhash, and Parija. "Poxviruses." Textbook of Microbiology and Immunity. Ed. Chandra. India: Elsevior, 2009. 484. Print.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Berwald, Juli. "Variola Virus." Encyclopedia of Espionage, Intelligence, and Security. 2004.Encyclopedia.com. 28 Oct. 2015 <http://www.encyclopedia.com>

- ↑ "PENN Medicine News: Penn Researchers Determine Structure of Smallpox Virus Protein Bound to DNA." PENN Medicine News: Penn Researchers Determine Structure of Smallpox Virus Protein Bound to DNA. PENN Medicine, 4 Aug. 2006. Web. 28 Oct. 2015. <http://www.uphs.upenn.edu/news/News_Releases/aug06/smlpxenz.htm>

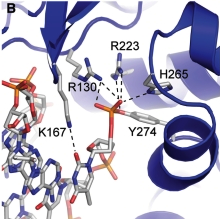

- ↑ Perry, Kay, Young Hwang, Frederic D. Bushman, and Gregory D. Van Duyne. "Insights from the Structure of a Smallpox Virus Topoisomerase-DNA Transition State Mimic." Structure (London, England : 1993). U.S. National Library of Medicine, n.d. Web. 28 Oct. 2015. <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2822398/>

- ↑ Minkah, Nana et al. “Variola Virus Topoisomerase: DNA Cleavage Specificity and Distribution of Sites in Poxvirus Genomes.” Virology 365.1 (2007): 60–69.PMC. Web. 16 Nov. 2015

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Baker, Nicole M., Rakhi Rajan, and Alfonso Mondragón. “Structural Studies of Type I Topoisomerases.” Nucleic Acids Research 37.3 (2009): 693–701. PMC. Web. 16 Nov. 2015>