Journal:Acta Cryst D:S2059798325007065

From Proteopedia

(Difference between revisions)

| (54 intermediate revisions not shown.) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| - | <StructureSection load='' size='450' side='right' scene='10/1087243/ | + | <StructureSection load='' size='450' side='right' scene='10/1087243/018_initl_scene_png/1' caption='Hydroxynitrile lyase from Hevea brasiliensis (HbHNL) from a rubber tree and esterase SABP2 ([[1y7i]]) from Nicotiana tabacum share the α/β-hydrolase fold with a S-H-D catalytic triad, and 44% sequence identity, yet catalyze different reactions. Displacement of Cα atoms (ΔCα) in HbHNL ([[1yb6]]), as seen in the putty cartoon, shows that there are major differences in the conformation of the backbone even with such high sequence identity. A red, thick sausage indicates a displacement of ~3 Å'> |

===Crystal structures of forty- and seventy-one-substitution variants of hydroxynitrile lyase from rubber tree=== | ===Crystal structures of forty- and seventy-one-substitution variants of hydroxynitrile lyase from rubber tree=== | ||

| - | <big> | + | <big>Colin T. Pierce, Panhavuth Tan, Lauren R. Greenberg, Meghan E. Walsh, Ke Shi, Alana H. Nguyen, Elyssa L. Meixner, Sharad Sarak, Hideki Aihara, Robert L. Evans III, Romas J. Kazlauskas</big> <ref>doi: 10.1107/S2059798325007065</ref> |

<hr/> | <hr/> | ||

<b>Molecular Tour</b><br> | <b>Molecular Tour</b><br> | ||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

Converting one enzyme into another might seem straightforward—just swap out the residues that directly contact the substrate, and voilà, you have a new catalyst. However, new structural studies reveal that this intuitive approach falls dramatically short. Researchers attempting to transform hydroxynitrile lyase from rubber trees into an esterase discovered that modifying only the 16 residues directly surrounding the substrate produced disappointing catalytic activity. The real breakthrough came when they expanded their engineering to include 40 or 71 mutations, creating variants that not only matched but exceeded the performance of their target esterase. | Converting one enzyme into another might seem straightforward—just swap out the residues that directly contact the substrate, and voilà, you have a new catalyst. However, new structural studies reveal that this intuitive approach falls dramatically short. Researchers attempting to transform hydroxynitrile lyase from rubber trees into an esterase discovered that modifying only the 16 residues directly surrounding the substrate produced disappointing catalytic activity. The real breakthrough came when they expanded their engineering to include 40 or 71 mutations, creating variants that not only matched but exceeded the performance of their target esterase. | ||

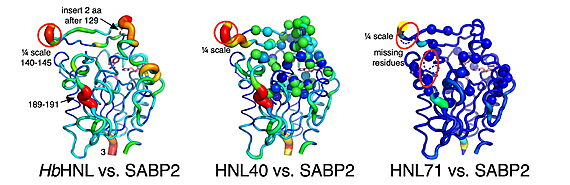

| - | The crystal structures explain this dramatic difference in performance. The 40-mutation variant (HNL40) shows a partially restored oxyanion hole—a critical structural pocket that stabilizes the high-energy transition state during ester hydrolysis—while the 71-mutation variant (HNL71) achieves nearly perfect geometric matching with the target enzyme. Remarkably, both variants develop new tunnels connecting the active site to the protein surface, potentially providing escape routes for reaction products. These structural changes occurred with most mutations being located 6-14 Å away from the substrate-binding site. | + | [[Image:Calpha_difference_vs_SABP2.jpg|thumb|center|570px|Displacement of Cα atoms (ΔCα) in HbHNL (PDB entry [[1yb6]]), HNL40 (PDB entry [[8sni]]), and HNL71 (PDB entry [[9clr]]) relative to wt SABP2 (PDB entry [[1y7i]]). ]] |

| + | |||

| + | The crystal structures explain this dramatic difference in performance of this α/β-hydrolase fold enzyme<ref>PMID:1409539</ref><ref>PMID:1678899</ref><ref>PMID:37582413</ref><ref>The [https://bioweb.supagro.inrae.fr/ESTHER/definition ''The ESTHER database'' website].</ref> . The 40-mutation variant (HNL40) shows a partially restored oxyanion hole—a critical structural pocket that stabilizes the high-energy transition state during ester hydrolysis—while the 71-mutation variant (HNL71) achieves nearly perfect geometric matching with the target enzyme. Active-site & oxyanion hole of; <scene name='10/1087243/018_act_site_oxyanion_hole/10'>SABP2</scene><ref>PMID:15668381</ref>, superposition of <scene name='10/1087243/018_act_site_oxyanion_hole/11'>SABP2 vs HbHNL</scene><ref>PMID:8805565</ref>, superposition of <scene name='10/1087243/018_act_site_oxyanion_hole/13'>SABP2 vs HNL40</scene>, superposition of <scene name='10/1087243/018_act_site_oxyanion_hole/14'>SABP2 vs HNL71</scene>. Remarkably, both variants, ''i.e.'', HNL40 and HNL71, develop new tunnels connecting the active site to the protein surface, potentially providing escape routes for reaction products. These structural changes occurred with most mutations being located 6-14 Å away from the substrate-binding site. | ||

These results reveal a sophisticated network where 'second-shell' residues, located beyond direct substrate contact, orchestrate catalytic efficiency through long-range effects. This finding suggests that creating truly efficient enzymes requires reengineering entire structural neighborhoods—a principle that could revolutionize approaches to enzyme design for biotechnology and medicine and help explain why natural enzymes maintain such complex architectures. | These results reveal a sophisticated network where 'second-shell' residues, located beyond direct substrate contact, orchestrate catalytic efficiency through long-range effects. This finding suggests that creating truly efficient enzymes requires reengineering entire structural neighborhoods—a principle that could revolutionize approaches to enzyme design for biotechnology and medicine and help explain why natural enzymes maintain such complex architectures. | ||

Current revision

| |||||||||||

This page complements a publication in scientific journals and is one of the Proteopedia's Interactive 3D Complement pages. For aditional details please see I3DC.