This old version of Proteopedia is provided for student assignments while the new version is undergoing repairs. Content and edits done in this old version of Proteopedia after March 1, 2026 will eventually be lost when it is retired in about June of 2026.

Apply for new accounts at the new Proteopedia. Your logins will work in both the old and new versions.

CRISPR-Cas9

From Proteopedia

(Difference between revisions)

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

cleaves the non-target DNA strand through a two-metal ion mechanism, as in other RNase H superfamily endonucleases. The HNH domain of SaCas9 has a ββα-metal fold, and shares structural similarity with those of SpCas9 (27% identity, rmsd of 1.8 A˚ for 93 equivalent Ca atoms) and AnCas9 (18% identity, rmsd of 2.6 A˚ for 98 equivalent Ca atoms). Asp556, His557, and Asn580 of SaCas9 are located at positions similar to those of the catalytic residues of SpCas9 (Asp839, His840, and Asn863) and AnCas9 (Asp581, His582, and Asn606). Indeed, the H557A and N580A mutants of SaCas9 almost completely lacked DNA cleavage activity, suggesting that the SaCas9 HNH domain cleaves the target DNA strand through a one-metal ion mechanism, as in other ββα-metal endonucleases. A structural comparison of SaCas9 with SpCas9 and AnCas9 revealed that the RuvC and HNH domains are connected by α-helical linkers, L1 and L2, and that notable differences exist in the relative arrangements between the two nuclease domains. A biochemical study suggested that PAM duplex binding to SpCas9 facilitates the cleavage of the target DNA strand by the HNH domain. However, in the PAM-containing quaternary complex structures of SaCas9 and SpCas9, the HNH domains are distant from the cleavage site of the target DNA strand. A structural comparison of SaCas9 with Thermus thermophilus RuvC in complex with a Holliday junction substrate indicated steric clashes between the L1 linker and the modeled non-target DNA strand, bound to the active site of the SaCas9 RuvC domain. These observations suggested that the binding of the non-target DNA strand to the RuvC domain may facilitate a conformational change of L1, thereby bringing the HNH domain to the scissile phosphate group in the target DNA strand. | cleaves the non-target DNA strand through a two-metal ion mechanism, as in other RNase H superfamily endonucleases. The HNH domain of SaCas9 has a ββα-metal fold, and shares structural similarity with those of SpCas9 (27% identity, rmsd of 1.8 A˚ for 93 equivalent Ca atoms) and AnCas9 (18% identity, rmsd of 2.6 A˚ for 98 equivalent Ca atoms). Asp556, His557, and Asn580 of SaCas9 are located at positions similar to those of the catalytic residues of SpCas9 (Asp839, His840, and Asn863) and AnCas9 (Asp581, His582, and Asn606). Indeed, the H557A and N580A mutants of SaCas9 almost completely lacked DNA cleavage activity, suggesting that the SaCas9 HNH domain cleaves the target DNA strand through a one-metal ion mechanism, as in other ββα-metal endonucleases. A structural comparison of SaCas9 with SpCas9 and AnCas9 revealed that the RuvC and HNH domains are connected by α-helical linkers, L1 and L2, and that notable differences exist in the relative arrangements between the two nuclease domains. A biochemical study suggested that PAM duplex binding to SpCas9 facilitates the cleavage of the target DNA strand by the HNH domain. However, in the PAM-containing quaternary complex structures of SaCas9 and SpCas9, the HNH domains are distant from the cleavage site of the target DNA strand. A structural comparison of SaCas9 with Thermus thermophilus RuvC in complex with a Holliday junction substrate indicated steric clashes between the L1 linker and the modeled non-target DNA strand, bound to the active site of the SaCas9 RuvC domain. These observations suggested that the binding of the non-target DNA strand to the RuvC domain may facilitate a conformational change of L1, thereby bringing the HNH domain to the scissile phosphate group in the target DNA strand. | ||

| - | Structure-Guided Engineering of SaCas9 Transcription Activators and Inducible Nucleases | + | '''Structure-Guided Engineering of SaCas9 Transcription Activators and Inducible Nucleases''' |

| - | Using the crystal structure of SaCas9, we sought to conduct | + | |

| - | structure-guided engineering to further expand the | + | Using the crystal structure of SaCas9, we sought to conduct structure-guided engineering to further expand the CRISPR-Cas9 |

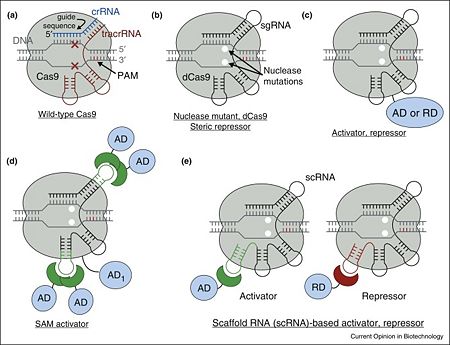

| - | toolbox, as we have done previously using the SpCas9 | + | toolbox, as we have done previously using the SpCas9 crystal structure. Given the similarities in the overall domain organizations of SaCas9 and SpCas9, we initially explored the feasibility of engineering the SaCas9 sgRNA, to develop robust transcription activators. In the SpCas9 structure, the tetraloop and stem loop 2 of the sgRNA are exposed to the solvent, and permitted the insertion of RNA aptamers into the sgRNA to create robust RNA-guided transcription activators. To generate the SaCas9-based activator system, a catalytically inactive version of SaCas9 (dSaCas9) was created by introducing the D10A and N580A mutations to inactivate the RuvC and HNH domains, respectively, and attached VP64 to the C terminus of dSaCas9. The sgRNA scaffold was modified by the insertion of the MS2 aptamer stem loop (MS2-SL), to allow the recruitment of MS2-p65-HSF1 transcriptional activation modules. To evaluate the dSaCas9-based activator design, a transcriptional activation reporter system was constructed, consisting of tandem sgRNA target sites upstream of a minimal CMV promoter driving the expression of the fluorescent reporter gene mKate2. An additional transcriptional termination signal upstream of the reporter cassette was included, to reduce the background previously observed in a similar reporter. Robust activation of mKate2 transcription was observed when the engineered sgRNA complementary to the target sites was expressed, whereas the non-binding sgRNA had no detectable effect. Based on a screening of different sgRNA designs with this reporter assay, was found that the insertions of MS2-SL into the tetraloop and putative stem loop 2 induced strong activation in our reporter system, whereas the insertion of MS2-SL into stem loop 1 yielded modest activation, consistent with the structural data. The single insertion of MS2-SL into the tetraloop was the simplest design that yielded strong transcriptional activation. Using this optimal sgRNA design, we further tested the activation of endogenous targets in the human genome. Two guides were selected each for the human ASCL1 and MYOD1 genomic loci, and demonstrated that the dSaCas9-based activator system activated both genes to levels comparable to those of the dSpCas9-based activator. Given that the sgRNAs for SaCas9 and SpCas9 are not interchangeable, the SaCas9-based transcription activator platform complements the SpCas9-based activator systems, by allowing the independent activation of different sets of genes. The SpCas9 structure also facilitated the rational design of split-Cas9s, which can be further engineered into an inducible system. This SaCas9 structure revealed several flexible regions in SaCas9 that could likewise serve as potential split sites. Three versions of a split-SaCas9 were created, and two of them showed robust cleavage activity at the endogenous EMX1 target locus. Using the best split design, inducible schemes were then tested based on the abscisic acid (ABA) sensing system, as well as two versions of the rapamycin-inducible FKBP/FRB system. All three systems were able to support inducible SaCas9 cleavage activity, demonstrating the possibility of an inducible, split-SaCas9 design; however, further optimization is required to increase its efficiency and reduce its background activity. |

| - | crystal structure. Given the similarities in the overall domain | + | |

| - | organizations of SaCas9 and SpCas9, we initially explored the | + | |

| - | feasibility of engineering the SaCas9 sgRNA, to develop robust | + | |

| - | transcription activators. In the SpCas9 structure, the tetraloop | + | |

| - | and stem loop 2 of the sgRNA are exposed to the solvent | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | permitted the insertion of RNA aptamers into the sgRNA to | + | |

| - | create robust RNA-guided transcription activators | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | by introducing the D10A and N580A mutations to inactivate the | + | |

| - | RuvC and HNH domains, respectively, and attached VP64 to | + | |

| - | the C terminus of dSaCas9 | + | |

| - | was modified by the insertion of the MS2 aptamer stem loop | + | |

| - | (MS2-SL), to allow the recruitment of MS2-p65-HSF1 transcriptional | + | |

| - | activation modules | + | |

| - | based activator design, | + | |

| - | activation reporter system, consisting of tandem sgRNA target sites upstream of a minimal CMV promoter driving the expression | + | |

| - | of the fluorescent reporter gene mKate2 | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | termination signal upstream of the reporter cassette, to reduce | + | |

| - | the background previously observed in a similar reporter | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | complementary to the target sites, whereas the non-binding | + | |

| - | sgRNA had no detectable effect | + | |

| - | screening of different sgRNA designs with this reporter assay, | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | putative stem loop 2 induced strong activation in our reporter | + | |

| - | system, whereas the insertion of MS2-SL into stem loop 1 | + | |

| - | yielded modest activation, consistent with the structural data | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | was the simplest design that yielded strong transcriptional activation. | + | |

| - | Using this optimal sgRNA design, we further tested the | + | |

| - | activation of endogenous targets in the human genome. | + | |

| - | selected | + | |

| - | genomic loci, and demonstrated that the dSaCas9-based activator | + | |

| - | system activated both genes to levels comparable to | + | |

| - | those of the dSpCas9-based activator | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | SpCas9 are not interchangeable, the SaCas9-based transcription | + | |

| - | activator platform complements the SpCas9-based activator | + | |

| - | systems, by allowing the independent activation of | + | |

| - | different sets of genes. The SpCas9 structure also facilitated the rational design of | + | |

| - | split-Cas9s | + | |

| - | can be further engineered into an inducible system | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | in SaCas9 that could likewise serve as potential split sites | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | of them showed robust cleavage activity at the endogenous | + | |

| - | EMX1 target locus | + | |

| - | then tested | + | |

| - | (ABA) sensing system | + | |

| - | of the rapamycin-inducible FKBP/FRB system | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | support inducible SaCas9 cleavage activity, demonstrating the | + | |

| - | possibility of an inducible, split-SaCas9 design; however, further | + | |

| - | optimization is required to increase its efficiency and reduce its | + | |

| - | background activity | + | |

=See aslo= | =See aslo= | ||

Revision as of 14:28, 30 August 2018

| |||||||||||

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Didovyk A, Borek B, Tsimring L, Hasty J. Transcriptional regulation with CRISPR-Cas9: principles, advances, and applications. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2016 Aug;40:177-84. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2016.06.003. Epub, 2016 Jun 23. PMID:27344519 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2016.06.003

- ↑ Brophy JA, Voigt CA. Principles of genetic circuit design. Nat Methods. 2014 May;11(5):508-20. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2926. PMID:24781324 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2926

- ↑ Straubeta A, Lahaye T. Zinc fingers, TAL effectors, or Cas9-based DNA binding proteins: what's best for targeting desired genome loci? Mol Plant. 2013 Sep;6(5):1384-7. doi: 10.1093/mp/sst075. Epub 2013 May 29. PMID:23718948 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/mp/sst075

- ↑ Sander JD, Joung JK. CRISPR-Cas systems for editing, regulating and targeting genomes. Nat Biotechnol. 2014 Apr;32(4):347-55. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2842. Epub 2014 Mar 2. PMID:24584096 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2842

- ↑ Marraffini LA. CRISPR-Cas immunity in prokaryotes. Nature. 2015 Oct 1;526(7571):55-61. doi: 10.1038/nature15386. PMID:26432244 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature15386

- ↑ Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Alkhnbashi OS, Costa F, Shah SA, Saunders SJ, Barrangou R, Brouns SJ, Charpentier E, Haft DH, Horvath P, Moineau S, Mojica FJ, Terns RM, Terns MP, White MF, Yakunin AF, Garrett RA, van der Oost J, Backofen R, Koonin EV. An updated evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015 Nov;13(11):722-36. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3569. Epub 2015, Sep 28. PMID:26411297 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro3569

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Jiang F, Zhou K, Ma L, Gressel S, Doudna JA. STRUCTURAL BIOLOGY. A Cas9-guide RNA complex preorganized for target DNA recognition. Science. 2015 Jun 26;348(6242):1477-81. doi: 10.1126/science.aab1452. PMID:26113724 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.aab1452

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012 Aug 17;337(6096):816-21. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. Epub 2012, Jun 28. PMID:22745249 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1225829

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Gasiunas G, Barrangou R, Horvath P, Siksnys V. Cas9-crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex mediates specific DNA cleavage for adaptive immunity in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 Sep 25;109(39):E2579-86. Epub 2012 Sep 4. PMID:22949671 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1208507109

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Qi LS, Larson MH, Gilbert LA, Doudna JA, Weissman JS, Arkin AP, Lim WA. Repurposing CRISPR as an RNA-guided platform for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Cell. 2013 Feb 28;152(5):1173-83. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.022. PMID:23452860 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.022

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Bikard D, Jiang W, Samai P, Hochschild A, Zhang F, Marraffini LA. Programmable repression and activation of bacterial gene expression using an engineered CRISPR-Cas system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013 Aug;41(15):7429-37. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt520. Epub 2013, Jun 12. PMID:23761437 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkt520

- ↑ Kuscu C, Arslan S, Singh R, Thorpe J, Adli M. Genome-wide analysis reveals characteristics of off-target sites bound by the Cas9 endonuclease. Nat Biotechnol. 2014 Jul;32(7):677-83. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2916. Epub 2014 May 18. PMID:24837660 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2916

- ↑ Jinek M, Jiang F, Taylor DW, Sternberg SH, Kaya E, Ma E, Anders C, Hauer M, Zhou K, Lin S, Kaplan M, Iavarone AT, Charpentier E, Nogales E, Doudna JA. Structures of Cas9 Endonucleases Reveal RNA-Mediated Conformational Activation. Science. 2014 Feb 6. PMID:24505130 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1247997

- ↑ Nishimasu H, Ran FA, Hsu PD, Konermann S, Shehata SI, Dohmae N, Ishitani R, Zhang F, Nureki O. Crystal structure of Cas9 in complex with guide RNA and target DNA. Cell. 2014 Feb 27;156(5):935-49. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.001. Epub 2014 Feb, 13. PMID:24529477 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.001

- ↑ Jiang F, Taylor DW, Chen JS, Kornfeld JE, Zhou K, Thompson AJ, Nogales E, Doudna JA. Structures of a CRISPR-Cas9 R-loop complex primed for DNA cleavage. Science. 2016 Jan 14. pii: aad8282. PMID:26841432 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.aad8282

- ↑ Wei Y, Terns RM, Terns MP. Cas9 function and host genome sampling in Type II-A CRISPR-Cas adaptation. Genes Dev. 2015 Feb 15;29(4):356-61. doi: 10.1101/gad.257550.114. PMID:25691466 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.257550.114

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Heler R, Samai P, Modell JW, Weiner C, Goldberg GW, Bikard D, Marraffini LA. Cas9 specifies functional viral targets during CRISPR-Cas adaptation. Nature. 2015 Mar 12;519(7542):199-202. doi: 10.1038/nature14245. Epub 2015 Feb, 18. PMID:25707807 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature14245

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Nielsen AA, Voigt CA. Multi-input CRISPR/Cas genetic circuits that interface host regulatory networks. Mol Syst Biol. 2014 Nov 24;10:763. doi: 10.15252/msb.20145735. PMID:25422271

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Didovyk A, Borek B, Hasty J, Tsimring L. Orthogonal Modular Gene Repression in Escherichia coli Using Engineered CRISPR/Cas9. ACS Synth Biol. 2016 Jan 15;5(1):81-8. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.5b00147. Epub 2015 , Sep 30. PMID:26390083 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acssynbio.5b00147

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Gilbert LA, Larson MH, Morsut L, Liu Z, Brar GA, Torres SE, Stern-Ginossar N, Brandman O, Whitehead EH, Doudna JA, Lim WA, Weissman JS, Qi LS. CRISPR-mediated modular RNA-guided regulation of transcription in eukaryotes. Cell. 2013 Jul 18;154(2):442-51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.044. Epub 2013 Jul, 11. PMID:23849981 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.044

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Farzadfard F, Perli SD, Lu TK. Tunable and multifunctional eukaryotic transcription factors based on CRISPR/Cas. ACS Synth Biol. 2013 Oct 18;2(10):604-13. doi: 10.1021/sb400081r. Epub 2013 Sep, 11. PMID:23977949 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/sb400081r

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Kiani S, Beal J, Ebrahimkhani MR, Huh J, Hall RN, Xie Z, Li Y, Weiss R. CRISPR transcriptional repression devices and layered circuits in mammalian cells. Nat Methods. 2014 Jul;11(7):723-6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2969. Epub 2014 May 5. PMID:24797424 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2969

- ↑ Nishimasu H, Cong L, Yan WX, Ran FA, Zetsche B, Li Y, Kurabayashi A, Ishitani R, Zhang F, Nureki O. Crystal Structure of Staphylococcus aureus Cas9. Cell. 2015 Aug 27;162(5):1113-26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.007. PMID:26317473 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.007