Sandbox reserved 659

From Proteopedia

(→Beta Lactoglobulin) |

|||

| (12 intermediate revisions not shown.) | |||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

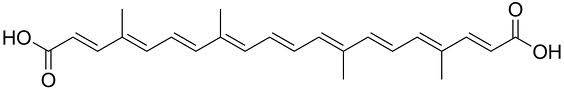

Cheddar cheese making process, norbixin leaches into the whey during the draining of the curd. Norbixin, a carotenoid extracted from the bixa orellana seed and added to cheese milk to give Cheddar its expected yellow flavor, would also contribute yellow color to the final product into which the whey ingredient is added. To prevent discoloration of the final product, whey is bleached by either hydrogen peroxide or benzoyl peroxide. In addition to a white color, this also causes lipid oxidation and associated off flavors. | Cheddar cheese making process, norbixin leaches into the whey during the draining of the curd. Norbixin, a carotenoid extracted from the bixa orellana seed and added to cheese milk to give Cheddar its expected yellow flavor, would also contribute yellow color to the final product into which the whey ingredient is added. To prevent discoloration of the final product, whey is bleached by either hydrogen peroxide or benzoyl peroxide. In addition to a white color, this also causes lipid oxidation and associated off flavors. | ||

| - | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Picture2.jpg|thumb|right|260px|frame|Norbixin]] |

| + | |||

[[Image:Picture6.jpg|thumb|right|260px|frame|Whey production process]] | [[Image:Picture6.jpg|thumb|right|260px|frame|Whey production process]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Picture4.png|thumb|left|260px|frame|Whey protein powder]] | ||

| + | |||

[[Image:Picture3.png|thumb|center|610px|]] | [[Image:Picture3.png|thumb|center|610px|]] | ||

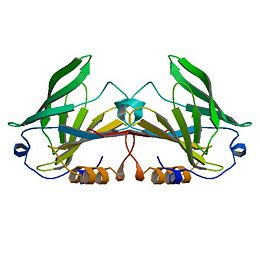

<StructureSection load='1B8E' size='350' side='right' caption='Structure of Beta Lactoglobulin (PDB entry [[1B8E]])' scene=''> | <StructureSection load='1B8E' size='350' side='right' caption='Structure of Beta Lactoglobulin (PDB entry [[1B8E]])' scene=''> | ||

| - | β-Lactoglobulin is a small protein | + | β-Lactoglobulin is a small protein with 162 amino acid residues (Mr ∼18,400). β-LG folds up into an 8-stranded, antiparallel β-barrel with a 3-turn α-helix on the outer surface and a ninth β-strand flanking the first strand. The ninth β-strand forms the dimer interface in cow and sheep proteins. The calyx, or β-barrel, is conical and serves as the ligand binding sight for small hydrophobic ligands. It is made of β-strands A-D forming one sheet, and strands E-H forming a second. Strand A turns at a right angle and the C-terminal end forms an antiparallel strand with H. A 3-turn helix between strands G and H is located on the outer surface of the β-barrel between strands G and H. The loops that connect the β-strands at the closed end of the calyx, BC, DE, and FG are generally quite short, whereas those at the open end are significantly longer and more flexible (Kontopidis, 2004). This becomes especially important when considering conformational changes at different pH values. Specifically, the EF loops can act as a “gate”, opening or closing access to and from the internal binding site. At acidic pH the “gate” closes while at neutral and basic pH values the “gate” is open, allowing for ligand binding at the hydrophobic binding site. The gate “hinge” is Glu89 (Kontopidis, 2004). |

| - | + | The free Cys121 has a reactive thiol group, whose activity parallels the pH dependency of the Tanford transition and is involved with the denaturation and aggregation of the system (Havea et al., 2001).. It is situated on the outer surfaced of the β-barrel and underneath the α-helix, which offers it some protection from the solvent and pH effects. | |

| - | The free Cys121, with its reactive thiol group, has a pH-dependent activity that parallels that of the Tanford transition, and its involvement in the denaturation and aggregation behavior is now firmly established (Havea et al., 2001). The residue is situated on the outer surface of the β-barrel on strand H, under the α-helix, and quite some distance from the EF loop. The effect of this is to mask its accessibility to solvent, particularly at low pH. Reaction with heavy metals like Hg2+ or Cd2+ does occur at most pH values and leads to a dissociation of the dimer. Indeed, reaction of the Cys with almost any thiol reagent appears to enhance dissociation into monomers (McKenzie and Sawyer, 1967; Hambling et al., 1992). | ||

| - | |||

| - | The CD and GH loops in many of the crystallographic analyses are indistinct, and the similarly indistinct nature of the extended AB loop led to the original misthreading of the amino acid sequence into the first electron density map (Papiz et al., 1986; Brownlow et al., 1997). β-Strand I is on the opposite side of strand A from strand H and forms an antiparallel interaction with the same strand of the second monomer. The other dimer-stabilizing interaction comes from the AB loop, where there is an ion pair from Asp33 of one subunit to Arg40 of the other. It is interesting to note that although strand I also exists in the porcine and equine β-LG structures, albeit with a slightly modified sequence, as do the Asp and Arg residues, no similar dimerization occurs at physiological pH. Indeed, site-directed mutagenesis designed to disrupt one or the other of these interactions, or better, both, produces a monomeric bovine protein (Sakurai and Goto, 2002; Wilson and Holt, to be published). There is no direct interaction between the α-helixes, which are antiparallel on the outer surface of the molecule with the polypeptide chains, some 12 Å apart. The closest approach of any atoms of the helix in the A subunit from the triclinic lattice X structure to the helix in the B subunit is 5.8Å, and this involves the flexible side chains of Asp137A and Arg148B and vice versa. | ||

| - | |||

| - | The structure of β-LG has also been determined by NMR techniques by several groups (Belloque and Smith, 1998; Fogolari et al., 1998; Kuwata et al., 1998; Uhrinova et al., 2000) and includes the equine structure (Kobayashi et al., 2000). The bovine protein is monomeric at pH values below 3, and the structure has been determined at this pH. Although there is no matching crystal structure at this pH where flat hexagonal plates of poor diffraction quality can be grown, the structure of the core of the protein is well conserved. However, significant differences do exist, and these have been critically reviewed (Jameson et al., 2002); it is not surprising that it is the external loops that contain these major differences. | ||

</StructureSection> | </StructureSection> | ||

| Line 33: | Line 32: | ||

<StructureSection load='1bso' size='280' side='right' caption='Structure of Beta Lactoglobulin with 12-BROMODODECANOIC ACID (PDB entry [[1bso]])' scene=''> | <StructureSection load='1bso' size='280' side='right' caption='Structure of Beta Lactoglobulin with 12-BROMODODECANOIC ACID (PDB entry [[1bso]])' scene=''> | ||

| - | + | While no definite physiological function has been attributed to β-LG, several possibilities do exist. As a lipocalin it only stands to reason that most suggestions involve a role in molecular transport of small hydrophobic ligand transport (Kontopidis et al., 2002). Most research concentrates on the lactating cell or the neonate. β-Lactoglobulin does bind to fatty acids of intermediate to long length and retinol. It is very similar in structure to plasma retinol binding protein. Genetic variation does throw some doubt on these suggestions however, as β-Lactoglobulin in some species do not bind with fatty acids (Perez et al., 1989, 1993). This would suggest that its main function is in fact, not as a fatty acid transporter. It also seems unnecessary as a retinol binding transporting seeing as retinol associates more strongly with the fat in milk and does not depend on β-LG as its primary transporter. Data on β-LG’s role as an activity-modulator tends to be circumstantial. It has been suggested that the function of β-LG is directly related to maternal physiology (Kontopidis et al., 2002). | |

| + | Nutritional value seems to be a valid purpose for β-LG. In the case of many species, the gene determining β-LG production has undergone a gene duplication and is involved more with nutrition than other functional purposes. Some species, like rodents, humans, and lagomorphs lost the ability to produce β-LG through formation of a pseudo-gene. While ligand binding and even the inhibition of harmful bacterial adhesion in the intestine (Ouwehand et al., 1997) are certainly useful properties, but neonatal nutrition continues to be the primary function. | ||

| - | When the species variation of β-LG sequences is examined along with that of the other lipocalins, what emerges is a family tree like that shown in Figure 4. The RBP are clearly distinct from the lactoglobulins, but there is one protein present in the endometrium, now called glycodelin (formerly PP14, inter alia), that is the closest relative to the β-LG-II gene product (Halttunen et al., 2000; Seppälä, 2002). There are also reports of RBP expressed in the endometrium of cow (Thomas et al., 1992; MacKenzie et al., 1997). Notice also that there is ruminant pseudo-gene identified in both cow and goat that is also most nearly related to the sequence of β-LG-II. Might it be that the protein glycodelin reflects the true, original function of β-LG as a protein involved in some aspect of fetal development in all mammals? In many species, the gene has undergone a gene duplication event and is expressed during lactation for nutritional purposes. More recently, some species, like rodents, lagomorphs, and man, have lost the function of one of these genes through formation of a pseudo-gene, resulting in the gene ceasing to be expressed. The biological properties of the milk protein, such as ligand binding and inhibiting harmful bacterial adhesion in the intestine (Ouwehand et al., 1997) that have been identified, are clearly useful to each species but are subsidiary to those of neonatal nutrition. On the other hand, it is known that low levels of β-LG are expressed in the cow throughout the dry period in a manner that is distinct from α-LA and the caseins (Aslam et al., 1994). Whether this is indicative of another more physiological role for β-LG in the changes that occur to the mammary gland during this period remains unclear at present. | ||

</StructureSection> | </StructureSection> | ||

| Line 45: | Line 44: | ||

<StructureSection load='2blg' size='280' side='right' caption='Structure of Beta Lactoglobulin at pH 8.2 (PDB entry [[2blg]])' scene=''> | <StructureSection load='2blg' size='280' side='right' caption='Structure of Beta Lactoglobulin at pH 8.2 (PDB entry [[2blg]])' scene=''> | ||

| - | + | The structures of the trigonal crystal form of bovine beta-lactoglobulin variant A at pH 6.2, 7.1, and 8.2 have been determined by X-ray diffraction methods at a resolution of 2.56, 2. 24, and 2.49 A, respectively. The corresponding values for R (Rfree) are 0.192 (0.240), 0.234 (0.279), and 0.232 (0.277). The C and N termini as well as two disulfide bonds are clearly defined in these models. The glutamate side chain of residue 89 is buried at pH 6.2 and becomes exposed at pH 7.1 and 8.2. This conformational change, involving the loop 85-90, provides a structural basis for a variety of pH-dependent chemical, physical, and spectroscopic phenomena, known as the Tanford transition. | |

| + | |||

| + | </StructureSection> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Implications=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | For the dairy industry, functionality and nutritional value are the primary issues when dealing with dairy proteins such as beta-lactoglobulin. The genetic variants referred to above in the ruminant species result in relatively minor amino acid differences, but the processing properties appear to be significantly affected even by these small changes, such that consideration has been given to removing the less favorable variants by selective breeding (Hill et al., 1997; Harris, 1997, Kontopidis et al., 2004). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ===References=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | G. Kontopidis, C. Holt, L. Sawyer. The ligand binding site of bovine β-lactoglobulin—Evidence for a function? J. Mol. Biol., 318 (2002), pp. 1043–1055 | ||

| + | |||

| + | J.P. Hill, M. Boland, A.F. Smith. The effect of β-lactoglobulin variants on milk powder manufacture and properties | ||

| + | J.P. Hill, M. Boland (Eds.), Milk Protein Polymorphism, International Dairy Federation, Brussels, Belgium (1997), pp. 372–394 | ||

| + | |||

| + | B.L. Harris. Selection to increase β-lactoglobulin B variant in New Zealand dairy cattle. J.P. Hill, M. Boland (Eds.), Milk Protein Polymorphism, International Dairy Federation, Brussels, Belgium (1997), pp. 467–473 | ||

| + | |||

| + | P. Havea, H. Singh, L.K. Creamer. Characterization of heat-induced aggregates of β-lactoglobulin, α-lactalbumin, and bovine serum albumin in a whey protein concentrate environment. J. Dairy Res., 68 (2001), pp. 483–497 | ||

| + | |||

| + | D.R. Flower, A.C.T. North, C.E. Sansom | ||

| + | The lipocalin protein family—structural and sequence overview. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1482 (2000), pp. 9–24 | ||

| + | |||

| + | A.C. Ouwehand, S.J. Salminen, M. Skurnik, P.L. Conway | ||

| + | Inhibition of pathogen adhesion by beta-lactoglobulin. Int. Dairy J., 7 (1997), pp. 685–692 | ||

| + | |||

| + | J.M.A. Tilley. The chemical and physical properties of bovine β-lactoglobulin | ||

| + | Dairy Sci. Abstr., 22 (1960), pp. 111–125 | ||

| + | |||

| + | R.L.J. Lyster. Reviews of the progress of dairy science. Section C. Chemistry of milk proteins. J. Dairy Res., 39 (1972), pp. 279–318 | ||

| + | |||

| + | J.E. Kinsella, D.M. Whitehead. Proteins in whey: Chemical, physical and functional properties. Adv. Food Nutr. Res., 33 (1989), pp. 343–438 | ||

| + | |||

| + | S.G. Hambling, A.S. McAlpine, L. Sawyer. β-Lactoglobulin. P.F. Fox (Ed.), Advanced Dairy Chemistry-I: Proteins, Elsevier, London, UK (1992), pp. 140–191 | ||

| + | |||

| + | L. Sawyer. β-Lactoglobulin. P.F. Fox, P. McSweeney (Eds.), Advanced Dairy Chemistry I (3rd ed.), Kluwer, Amsterdam, The Netherlands (2003), pp. 319–386 | ||

Current revision

Contents |

Beta Lactoglobulin

β-Lactoglobulin(β-LG) is the bulk constituent of whey protein in most ruminant species and is also present in the milks of most mammalian species, although not in rodent, human, and lagomorph milks. It has been studied extensively for some time ( Tilley, 1960; Lyster, 1972; Kinsella and Whitehead, 1987; Hambling et al., 1992; Sawyer, 2003). β-LG is a lipocalin as is seen through its amino-acid sequence and structure (Flower et al., 2000). Lipocalins are a varied family which bind small hydrophobic ligands, and often act as transporters in vivo. The purpose of β-LG, however, is not clear. Genetic variants of β-LG expressing genes have been reported, especially in cows and several nonruminant species (Kontopidis, 2004).

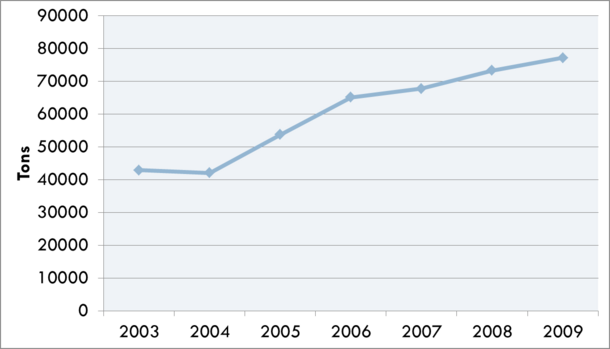

Whey is an often used food ingredient in the food industry and has many useful functional characteristics including foaming, gelling, thermal stability, emulsification, and protein fortification. It has also been suggested that it has many useful health benefits including exercise recovery, weight management, cardiovascular health, anti-cancer effects, anti-infection activity, wound repair, and infant nutrition. Human consumption of whey ingredients has steadily increased and has become more and more important to the dairy industry. An issue with whey ingredients is the subtle off flavor often associated with whey proteins. During the Cheddar cheese making process, norbixin leaches into the whey during the draining of the curd. Norbixin, a carotenoid extracted from the bixa orellana seed and added to cheese milk to give Cheddar its expected yellow flavor, would also contribute yellow color to the final product into which the whey ingredient is added. To prevent discoloration of the final product, whey is bleached by either hydrogen peroxide or benzoyl peroxide. In addition to a white color, this also causes lipid oxidation and associated off flavors.

| |||||||||||

Physiological Function of β-LG

| |||||||||||

Tanford Transition of β-LG

| |||||||||||

Implications

For the dairy industry, functionality and nutritional value are the primary issues when dealing with dairy proteins such as beta-lactoglobulin. The genetic variants referred to above in the ruminant species result in relatively minor amino acid differences, but the processing properties appear to be significantly affected even by these small changes, such that consideration has been given to removing the less favorable variants by selective breeding (Hill et al., 1997; Harris, 1997, Kontopidis et al., 2004).

References

G. Kontopidis, C. Holt, L. Sawyer. The ligand binding site of bovine β-lactoglobulin—Evidence for a function? J. Mol. Biol., 318 (2002), pp. 1043–1055

J.P. Hill, M. Boland, A.F. Smith. The effect of β-lactoglobulin variants on milk powder manufacture and properties J.P. Hill, M. Boland (Eds.), Milk Protein Polymorphism, International Dairy Federation, Brussels, Belgium (1997), pp. 372–394

B.L. Harris. Selection to increase β-lactoglobulin B variant in New Zealand dairy cattle. J.P. Hill, M. Boland (Eds.), Milk Protein Polymorphism, International Dairy Federation, Brussels, Belgium (1997), pp. 467–473

P. Havea, H. Singh, L.K. Creamer. Characterization of heat-induced aggregates of β-lactoglobulin, α-lactalbumin, and bovine serum albumin in a whey protein concentrate environment. J. Dairy Res., 68 (2001), pp. 483–497

D.R. Flower, A.C.T. North, C.E. Sansom The lipocalin protein family—structural and sequence overview. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1482 (2000), pp. 9–24

A.C. Ouwehand, S.J. Salminen, M. Skurnik, P.L. Conway Inhibition of pathogen adhesion by beta-lactoglobulin. Int. Dairy J., 7 (1997), pp. 685–692

J.M.A. Tilley. The chemical and physical properties of bovine β-lactoglobulin Dairy Sci. Abstr., 22 (1960), pp. 111–125

R.L.J. Lyster. Reviews of the progress of dairy science. Section C. Chemistry of milk proteins. J. Dairy Res., 39 (1972), pp. 279–318

J.E. Kinsella, D.M. Whitehead. Proteins in whey: Chemical, physical and functional properties. Adv. Food Nutr. Res., 33 (1989), pp. 343–438

S.G. Hambling, A.S. McAlpine, L. Sawyer. β-Lactoglobulin. P.F. Fox (Ed.), Advanced Dairy Chemistry-I: Proteins, Elsevier, London, UK (1992), pp. 140–191

L. Sawyer. β-Lactoglobulin. P.F. Fox, P. McSweeney (Eds.), Advanced Dairy Chemistry I (3rd ed.), Kluwer, Amsterdam, The Netherlands (2003), pp. 319–386